by James A. Bacon

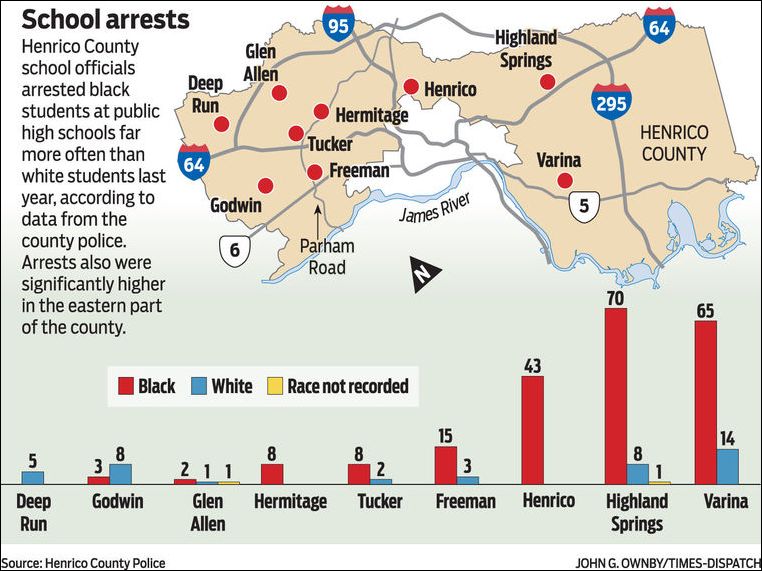

Black students comprise 39% of the public school student population in Henrico County but account for 80% of all the kids arrested for offenses committed in schools. That disparity, combined with the fact that black students are disproportionately suspended from Henrico schools, is something that some people find disturbing, according to the Sunday Times-Dispatch. Although the article does not explicitly describe the difference as an injustice, the headline entitled, “School data show racial disparity in Henrico,” certainly implies that it is. In the progressive/liberal worldview “disparities” between the races are ipso facto evidence of discrimination.

“If they don’t know they have a problem, they have their eyes closed,” said Claire Guthrie Gastanaga, executive director of the Virginia ACLU, which has made an issue of the differing rate of school suspensions in Henrico. “The numbers don’t lie, and the suspension rates are disproportionate as it relates to African-Americans, and I think we see that the arrest rates are as well,” said Tyrone Nelson, a black supervisor from the Varina district.

There are two very big problems with the article. First, it provides no evidence whatsoever that black students are disciplined more harshly than whites for comparable offenses. That evidence may exist somewhere but the article doesn’t provide it. Second, the article follows the standard victimization narrative of troubled black youths suffering from a system that is stacked against them. But it totally ignores the invisible victims of disorder in the schools — classmates, disproportionately black, whose educational experience is disrupted by the misbehavior. If we want to understand the “disparities” in educational achievement between the races, differences in school discipline is a factor worth exploring.

The incidence of disorderly behavior in schools is tightly correlated with the socio-economic characteristics of the student body. Families from “disadvantaged” backgrounds are more likely to suffer social disorders arising from economic insecurity, substance abuse, domestic violence and the lack of a biological father in the house. Youths raised in such an environment — especially adolescent males — are far more prone to disruptive and violent behavior at home, on the street and in school.

According to our trusty tool, the Virginia Department of Education SOL Assessment Build-a-Table, 65% of all economically disadvantaged students in Henrico County are black. Insofar as kids who get in enough trouble at school to get suspended or arrested are economically disadvantaged, more than half the so-called racial disparity disappears. A more refined look at the data — I would point to the presence of biological fathers in the household as a better indicator of a family’s ability to impose social norms on rebellious adolescent males — could show that the disparity disappears entirely. Conceivably, a closer look will show no such thing. We won’t know until we do the research. What is reckless, irresponsible and inflammatory is to assume, as a default proposition, that any differences in suspension and arrest rates reflects discrimination by schools and law enforcement.

Under investigation from the hyper-politicized U.S. Justice Department for the “disparity” in school suspensions, Henrico County authorities have been making an effort to cut that disparity. As the Times-Dispatch notes:

In the 2012-2013 school year, the number of suspensions in Henrico County schools dropped to 7,604 from 9,165 the year before, a 17 percent reduction. But the share of suspensions going to black students remained stubbornly high, rising almost half a point to nearly 77 percent.

Unless we’re willing to attribute some kind of subtle racism or prejudice to Henrico County principals and teachers — many of whom are black themselves, especially in the schools where discipline problems are the greatest — the logical conclusion is that the rules and procedures for administering discipline isn’t the problem. The kids are the problem.

There is, in fact, an injustice in this story. The injustice just happens to be the precise opposite of what is commonly asserted. The real problem is that disruptive behavior in the classroom has a negative impact on teacher morale and makes it harder for well-behaving students to learn.

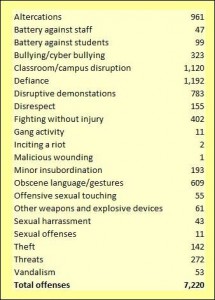

How prevalent is disruptive behavior in Henrico classrooms? According to the “Discipline, Crime and Violence Annual Report, 2012-2013,” we know that discipline issues are a big problem. Henrico County logged more than 7,200 disciplinary offenses during the 2012-2013 school year. Highlights are shown at left.

These are just the offenses that were recorded for the record. It goes without saying that many fights, scuffles, bullying and lesser offenses take place out of the sight of teachers and administrators, and much of the disruptive behavior in classroom is simply ignored because teachers learn that reporting it or complaining about it is a waste of time.

Who suffers from this behavior? The three high schools that account for the overwhelming majority of the arrests are overwhelmingly black. That means the students suffering from the disruption, bullying, scuffling and assaults also tend to be black. The well-behaved, law-abiding black kids who go to school and want to study find it more difficult to learn because the teachers are spending classroom time dealing with problem students instead of teaching.

There is important secondary fallout from the discipline problem: Teachers find it demoralizing. Teacher burn-out accounts for much of the high turn-over in schools serving low-income student students; teachers with experience and seniority seek employment in schools where they don’t have to contend with discipline issues. The result: teachers in schools serving low-income populations tend to have less seniority, maturity and experience teaching challenging student populations.

Making an issue of “disparities” in arrests and suspensions based on the paltry evidence presented by the Times-Dispatch is a gross injustice to Henrico school and law-enforcement officials who are trying to preserve a decent learning environment. Such articles distract from the far bigger problem of school discipline. If the T-D, the ACLU and other do-gooders want to help struggling black kids mired in under-performing schools, perhaps they should start by asking what effect the breakdown in discipline has on the kids who want to learn.