by James C. Sherlock

Healthcare costs are crowding out other spending by citizens and governments. All Virginians know this. Few understand, though, that their elected leaders in Richmond, who are recipients of huge campaign contributions from hospital interests, bear a significant share of the blame and some are actively working to increase costs further.

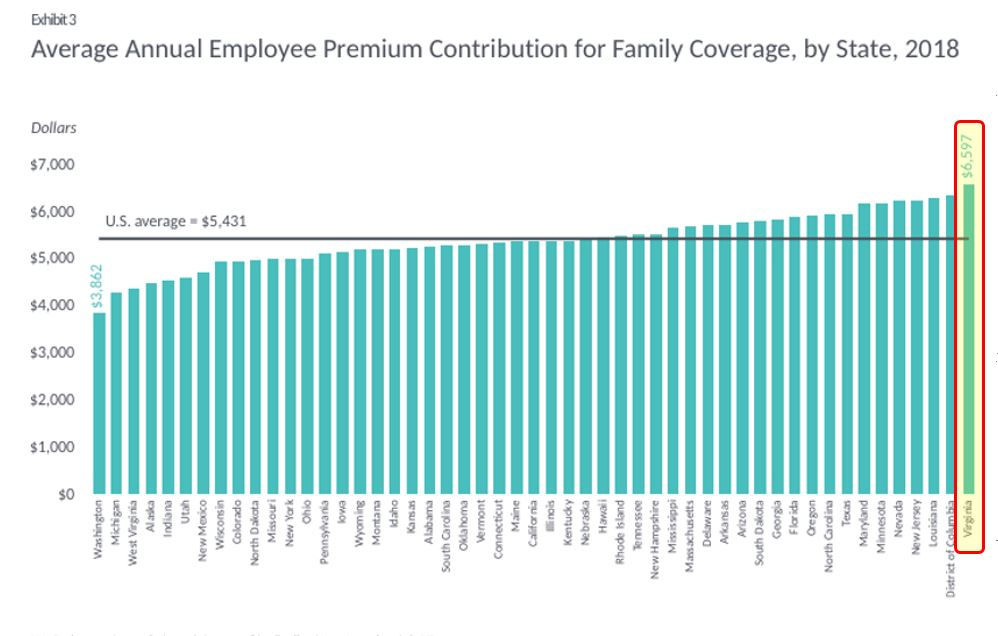

Virginia had the highest priced commercial health insurance in the country in 2018. (See chart above.) At $6,597, the 2018 average annual employee premium contribution for family health insurance coverage was the highest in the nation. The premium for single coverage in Virginia was the third highest.

The Affordable Care Act exchange is no better. The Centers of Medicare/ Medicaid database lists 16,900 lines of Silver plans and locations nationally in 2018. Virginia had 22 of the 55 highest priced, including 14 of the top 16. In the worst case in the nation, a 40-year-old couple with two children in the Charlottesville area paid almost $39,000 in premiums in 2018 for the less expensive of the only two family Silver policies available on the ACA exchange. Both were offered by Sentara’s Optima Health. With that policy, their out-of-pocket costs were capped at $14,700. Both policies were HMOs with no coverage for out-of-network providers. It was a Sentara network.

Hospital systems in Virginia’s five largest metro areas, either own their own health plans and insurers or have joined exclusive partnerships with one. Sentara, the largest, controls 63 corporations, 43 of which are for profit. Its non-profit subordinates include Optima Health and Sentara providers except its ambulatory surgery centers, which are for-profit partnerships.

Captive insurers are required to represent only their clients’ interests and their own when “negotiating” prices with fellow captive providers and when negotiating network access by competing providers. Yet the Charlottesville example and similar situations in Hampton Roads and Harrisonburg are difficult to explain any other way.

Nationally, health insurance premiums increased between 2013 and 2017 from $633 billion to $855 billion, or 35%. Incurred claims increased by exactly the same percentage. Over the same period, healthcare utilization increased less than 1%. Higher prices paid to healthcare providers and pharmaceutical makers are likely responsible.

Virginia health system profits

A Navigant study of the nation’s largest health systems showed that operating margins in 2018 averaged 2.92%. Health system reports to the Commonwealth showed the combined operating margin of acute care hospitals here was 8.2%. The difference between 3% and 8% with 2018 operating revenue of about $22 billion is over a billion dollars in one year. Those extraordinary Virginia margins were in years before Medicaid expansion and the accompanying reimbursement increases that could add another billion dollars in profits.

Regional monopolies are in control when pricing inpatient procedures to commercial insurers. All insurers including Medicare and Medicaid pay between 1.5 times and three times more for procedures performed in hospitals than by the same physicians in independent ambulatory care centers.

The Virginia Department of Health (VDH) has severely restricted ambulatory care access by awarding only 71 certificates for ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), about half of them to hospitals. The hospitals’ only competition in ambulatory care comes from fewer than 40 certificate-holding ambulatory surgical centers and the few diagnostic imaging centers. Maryland has 20% fewer people than Virginia but more than seven times as many ASCs, the vast majority physician-owned.

Ambulatory care including surgery and imagery for the vast majority of patients can be accomplished either in hospital outpatient departments or in detached ambulatory surgical centers. The same surgery by the same surgeon is far less expensive in the — unless a hospital owns that ASC and bills the procedures at hospital rates.

So, how did this happen?

The answer is found in bad public policy badly executed. We can directly thank Virginia’s Certificate of Public Need (COPN) and its irresponsible administration by VDH since 1973.

The COPN law enacted in 1973 gave VDH control over the construction and expansion of new hospitals, ambulatory care and diagnostic imagery centers and over the equipment necessary to operate them. Virginia has thus limited supply in the face of growing demand and some are apparently surprised that prices have risen.

Without legislative direction for 47 years, VDH years has used the COPN process both to create hospital monopolies in nearly every region of Virginia but Richmond and to severely restrict the creation of outpatient facilities as competitors to those hospitals. Monopolies have consequences, including control of prices and suppression of competitors.

Lawmakers have made no serious attempt either to limit rates of growth of the prices charged by those monopolies or to oversee their business practices. Both COPN and the permissive provider regulatory regime remain in place because, in creating regional monopolies, VDH simultaneously created a powerful political interest in most General Assembly districts.

Some hospital systems are both monopolies and self-declared non-profit charities. No state agency oversees the business activities of healthcare providers, monopolies or not. The Virginia Department of Taxation apparently counts on the Internal Revenue Service to oversee tax exempt entities, which avoid hundreds of millions in state and local taxes every year. Nationally, there are 250,000 self-identified entities large enough to warrant review of such things as executive salaries and charitable mission compliance. The IRS simply doesn’t do it.

The Justice Department is blocked from enforcing federal antitrust laws because the monopolies have been granted by the state. The Virginia Antitrust Act has never been enforced. Virginians would have been in a far better place if the Commonwealth had never passed COPN. But here we are and the General Assembly is poised to make it worse — lower access, less competition and higher cost. More on that soon.

James C. Sherlock, a Virginia Beach resident, is a retired Navy Captain and a certified enterprise architect. As a private citizen, he has researched and written about the business of healthcare in Virginia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.