by Richard W. Hall-Sizemore

The Commonwealth has been on a borrowing/building spree for the past few years and, as a result, its options for dealing with capital needs in the future may be constrained.

Since 1991, Virginia has voluntarily limited itself to the amount of tax-supported debt it would incur for capital projects. This “debt capacity” is measured in terms of the percentage of general fund revenues that need to be provided for debt service on outstanding capital bonds. The consensus between the legislature and the administration has been that projected debt service on tax-supported bonds should not exceed an average of five percent of general fund revenue over the ensuing ten years.

This voluntary debt capacity limit and the Commonwealth’s willingness to abide by it is one of several key factors used by rating agencies in their assessments of the state’s credit quality. Because Virginia is rated AAA by all three rating agencies and no one wants to jeopardize that status, keeping within the debt capacity limit has long been a factor to consider when deciding which capital projects to authorize.

The Debt Capacity Advisory Committee (DCAC) annually recommends the maximum amount of debt that should be issued in order to remain within the debt capacity limit. The membership of the DCAC consists of the Secretary of Finance, the directors of the four Finance agencies (DPB, Treasury, Taxation, and DOA), the director of JLARC, the Auditor of Pubic Accounts, the staff directors of the Senate Finance and House Appropriations Committees, and two citizen members appointed by the Governor.

The DCAC 2018 report is a clearly-written summary of the Commonwealth’s long-term debt and sets out the assumptions and calculations used to arrive at its recommendations on future debt authorization. To review the report in its entirety, go here.

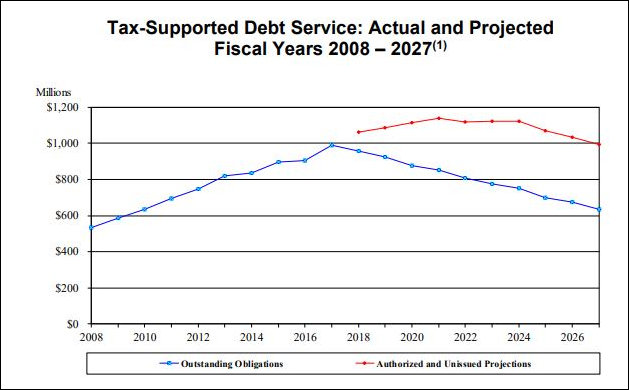

According to the DCAC, the outstanding balance of the category of debt used to finance capital projects increased from $5.10 billion at the end of FY 2009 to $10.35 billion at the end of FY 2018, a 103 percent increase. The annual debt service on this outstanding debt is expected to exceed $1 billion in FY 2019. A large part of the increase was a result of “significant authorizations for transportation bonds in 2007,” which resulted from the major transportation package adopted in the McDonnell years. However, there have also been significant authorizations for capital projects for state agencies and institutions of higher education.

By far, the greater part of the debt authorized for capital building projects has been for institutions of higher education. In the bond package authorized in the 2008 Special Session, a total of $1.4 billion in bonds was authorized to construct new buildings or to expand, repair, or renovate existing buildings. Of that amount, 69 percent, $965 million, was for higher education. There was another big bond bill in 2016, authorizing the issuance of $1.8 billion for capital projects. The General Assembly earmarked $1.77 billion, or 76 percent, of that amount for higher ed.

From one perspective, it made financial sense to issue a lot of debt over the past few years. The general economy was in recession and contractors were anxious for work and thus willing to keep their bids as low as possible. Furthermore, interest rates were low, thus reducing the overall costs of projects. However, those conditions are changing. Last summer and fall, the staff at the Department of General Services who coordinate the state’s capital outlay process, were reporting that bids on projects, especially in the western part of the state, were coming in higher than expected. Also, with the Federal Reserve raising interest rates, the rates on municipal bonds will probably increase, as noted by the DCAC.

With this background in mind, the DCAC reported that, based on its debt capacity model, “up to $671 million in additional debt could be authorized and issued in each of fiscal years 2019 and 2020.” Assuming the issuance of that amount for each year through fiscal year 2028, the DCAC projected that the average debt service for the ten-year period would be five percent of the projected general fund revenues. The debt service would exceed five percent in five of those years and be below five percent in the other five years. The DCAC model is based on the December 2018 revenue forecast produced by the Department of Taxation, with one important exception. It does not include the revenues related to the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the contingent, proposed refundable Earned Income Tax Credits. It does include the additional $82.5 million expected to be collected annually by expanding the collection of sales taxes on internet sales.

The total tax-supported debt authorized for FY 2019 in the Appropriation Act enacted by the 2018 General Assembly was $853 million, significantly higher than the current DCAC recommendation of $671 million. In the budget bill presented to the 2019 General Assembly, the Governor proposed the authorization of $693 million in new tax-supported debt, very close to the amount recommended by the DCAC. The major components of the FY 2019 authorizations were $330 million for harbor dredging in Hampton Roads by the Virginia Port Authority; $216 million for a variety of new construction and infrastructure projects for agencies and institutions of higher education; and $129 million for long term maintenance projects, distributed to all agencies and institutions of higher education with physical facilities. The largest items in the Governor’s FY 2020 proposal are a couple of projects totaling $248 million that are part of the Amazon incentive package; $132 million to upgrade the statewide radio system maintained by the State Police; $128 million for long term maintenance projects; and $121 million for designated agency projects that, with a couple of exceptions, are for infrastructure repair or upgrades.

The General Assembly is going to get a lot of pressure to add more tax-supported bond projects to those proposed by the Governor. Left out of the Governor’s proposed projects were numerous new construction projects for institutions of higher education that were authorized for planning by the General Assembly in 2016, with the implicit assurance that authorization to go forward to the construction phase would be considered in the 2019 Session. For most of those projects, the total planning has been completed. In the institutions’ budget requests submitted to the Governor for these projects, the total estimated cost of these projects was $839 million.

Adding to the pressure on the Commonwealth’s voluntary limit on debt capacity will be additional projects already identified and waiting in the wings. The 2018 General Assembly authorized planning for several higher ed projects, with a total estimated cost of $168 million, with the anticipation that they would be considered for construction authorization in the 2020 Session. The Governor has proposed, in the introduced budget, authorization of planning for eight major construction projects, with an estimated cost of $683 million. The largest project in this latter group is the replacement of Central State Hospital, the mental health hospital in Petersburg. There is a consensus that the project is needed, but the estimated $373 million price tag may be hard to swallow. In addition, the 2016 debt package is estimated to be underfunded by $70-80 million and the gap will probably grow as more projects go to bid. Furthermore, many agencies, such as the Department of Corrections, have physical facilities that are aging and will need major upgrades or renovations in the near future to remain functional. Finally, there are the long-term maintenance projects (roofs, HVAC, etc.) for which the General Assembly usually provides $50-100 million annually.

In summary, unless general fund revenues increase significantly, Governors and legislators will be facing some tough choices in the future if they want to keep the Commonwealth’s debt service commitments from exceeding the current debt capacity limits.

Richard W. Hall-Sizemore recently retired from a position in the Department of Planning and Budget.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.