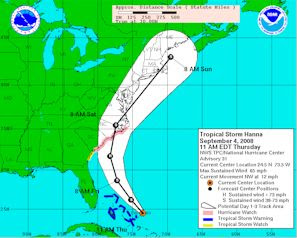

Tropical Storm Hanna is expected to graze the coast of Virginia this weekend on its northward path, and Gov. Timothy M. Kaine has declared a state of emergency. In a follow-up message, Attorney General Bob McDonnell issued a warning that the Virginia Post-Disaster Anti-Price Gouging Statute is now activated.

Tropical Storm Hanna is expected to graze the coast of Virginia this weekend on its northward path, and Gov. Timothy M. Kaine has declared a state of emergency. In a follow-up message, Attorney General Bob McDonnell issued a warning that the Virginia Post-Disaster Anti-Price Gouging Statute is now activated.

And what does that act do?

It “prohibits the charging of “unconscionable” prices for “necessary goods and services” within the affected area during the 30 day period following issuance of a declared state of emergency. The basic test under the statute is whether the price charged for the goods or services “grossly exceeds” the price charged immediately (within 10 days) before the disaster. “Necessary goods and services” includes those goods or services for which demand does, or is likely to, increase as a result of the disaster.

The AG’s office thoughtfully provided a “price gouging complaint form” so citizens can report offenders.

It will be interesting to see what impact the price-gouging statute has on the clean-up after the storm. I’m not persuaded that it will be especially helpful. It might even hurt. Let me explain:

One thing we can anticipate from the tropical storm is a glut of fallen trees. Trees on power lines. Trees on houses (some causing structural damage and others not). Trees across roads. Trees in driveways. Trees in the back yard. Trees in the woods. The urgency associated with clearing any given tree will vary widely. A tree blocking traffic or preventing a roof repair will be a priority; a tree simply looking unsightly in the front yard will be less of a priority.

There will be a finite number of tree service employees, even if they come in from miles around and work 16-hour days. They will not be able to clear everybody’s trees all at one time. Some people will have to wait. Who will decide whose tree gets cleared immediately and who has to wait?

Well, if tree service crews are able to respond to supply and demand and raise their rates to “unconscionable” levels, they will prioritize work based upon on peoples’ willingness to pay. That willingness to pay will reflect, among other things, the urgency of a given situation. Someone with a leaking roof will be willing to pay more than someone who wants to clear a tree from his back yard… which makes total sense.

What happens if tree service crews are worried about getting prosecuted if they charge “too much.” What happens if they don’t feel free to increase their rates? Perhaps they’ll work on a first-come, first-serve basis, regardless of priority. Perhaps some will work only 12 hours a day rather than 16. Perhaps, if they live in Richmond or Fredericksburg, some will figure it won’t pay to drive down to Hampton Roads and check into a hotel. Maybe they’ll just stay home. Maybe it’ll wind up taking twice as long to clear all the trees as it would have if people could charge the market price.

A similar logic applies to the sale of every other product and service, from electric generators to chainsaws, from repairing broken windows to supplying water, ice and food. Economic theory suggests that repressing prices will inflate demand, slow the arrival of new supplies, and create shortages.

Maybe it won’t work out that way. Maybe the inhabitants of eastern Virginia will all pitch in and share in a spontaneous display of good will towards their fellow man. We’ll see. It will be most fascinating to watch.