by James A. Bacon

On April 17 The Virginian-Pilot published an article with the following headline: “Not a speed trap, a race trap: Black Virginians say they’ve been racially profiled in and around Windsor for decades.”

The highly publicized traffic-stop encounter in which two white policemen pepper-sprayed Caron Nazario, a black army lieutenant, on U.S. 460, was not an anomaly, according to the Virginian-Pilot. Quoting the experiences of eight black former Virginia State University students and faculty, the newspaper provided anecdotal evidence that blacks have been targeted for ticketing by the three Ws, the towns of Windsor, Wakefield and Waverly.

“We as African Americans have traditionally acquiesced to the racial power dynamics that are displayed throughout policing on 460,” said Zoe Spencer, an assistant professor of sociology and criminology at VSU. “And while I believe Lt. Nazario’s situation was absolutely egregious, I would hypothesize that he is in no way the only one that experienced that kind of treatment.”

Clearly, there is a perception among many blacks that they are targeted for traffic offenses along U.S. 460. But is that perception based on reality? Are black motorists in Windsor and other small towns along U.S. 460 really stopped, ticketed and even dragged out of their cars because of their race?

The Virginian-Pilot provides only this statistical evidence to support its claim:

In Virginia, about 20% of the state’s 8.5 million residents are Black, but in Wakefield, Waverly and Windsor the percentage of cases involving Black people that land in General District Court, where speeding tickets and minor traffic citations are heard, is far higher. In 2018, 2019 and 2020, they accounted for at least 40% of the district court cases where those towns are listed as the location, according to an analysis of Virginia court data available through Virginiacourtdata.org.

That’s it. All the rest is anecdote.

460 corridor demographics. Here is the most obvious problem with the story: The fact that 20% of Virginia’s population is black is irrelevant to the analysis. A more pertinent question is what percentage of the motorists on U.S. 460 is black? An even more pertinent question is what percentage of traffic offenses is committed by blacks?

The answer to the first question is unknowable. The Commonwealth of Virginia does not track highway traffic by race. However, it is worth noting that U.S. 460 is one of two main routes — the other is Interstate 64 — connecting the Richmond and Hampton Roads metropolitan statistical areas, which are the two main black population centers in Virginia. Running through Petersburg, Prince George County, Sussex County, Isle of Wight County and Suffolk, U.S. 460 functions as the main street for communities along the route. (The towns of Waverly and Wakefield are located in Sussex and the Town of Windsor in Isle of Wight.) Here is the population breakdown for each locality along the route:

City Petersburg — population 32,000, 77% black

Prince George County — population 36,000, 32% black

Sussex County — population 12,000, 57% black

Isle of Wight County — population 36,000, 22% black

City of Suffolk — population 85,000, 41% black

In other words, if the traffic along U.S. 460 is representative of the population served by the highway, then one should not be surprised that roughly 40% of the traffic citations are for black motorists.

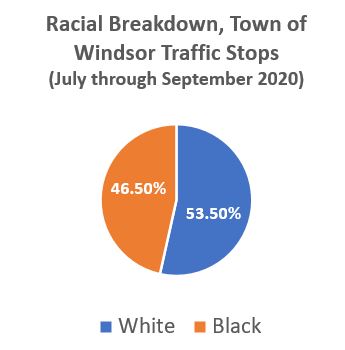

Town of Windsor traffic data. Towns and counties across Virginia have been required only since July 2020 to record the race, gender, and ethnicity of individuals stopped by the police. Joel Rubin, who is handling communications for the Town of Windsor, provided me with July-September 2020 traffic-stop data for the town. You can access the Excel file here. Please feel free to contest my analysis.

The file provides details of 506 stops for individuals whose race could be identified. (Only 7 were not identified.) Of those, the breakdown was:

The percentage of blacks stopped for traffic violations, 46.5%, was a little higher than for the population in the general area. However, the outcomes of the stops were the same for blacks and whites.

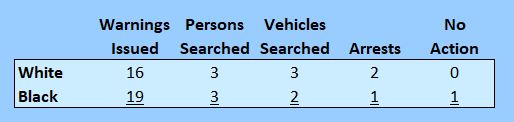

All but one stop was for a traffic violation. (One was for an equipment violation.) The vast majority of stops occurred on U.S. 460, and about three quarters of the stops were for speeding in a 35 mile-per-hour zone. (Windsor police policy is to pull vehicles exceeding the speed limit by 12 miles per hour.) In the overwhelming majority of cases, stops resulted in a citation/summons. But occasionally, motorists were let off with warnings. On rare occasion, drivers were searched, their vehicles were searched, and arrests were made. Here are the numbers broken down by race.

Black motorists enjoyed an 8.1% chance of being issued a warning and sent on their way without a ticket. White motorists had only a 5.9% chance of getting away with a warning. Put another way, black motorists stopped by Windsor police were marginally less likely to be ticketed. The numbers indicate that blacks were no more likely to be searched or have their cars searched than whites. Only one black motorist was arrested during this three-month period compared to two whites.

According to Rubin, on average of 17,000 vehicles travel daily along Route 460 as measured at the Windsor Boulevard intersection, or about 6.1 million vehicles annually. Those numbers imply between 1.5 million and 1.6 million trips during the July-to-September quarter. In other words, police pull only one in every 3,000 or so vehicles. The chances of a black person getting a ticket on any given day are minimal.

If there is anti-black bias in traffic enforcement by Windsor police, it is not visible in these data.

The visibility issue. Another problem with the “driving while black” narrative is that it is exceedingly difficult to identify the race of a driver until the car has stopped. Most traffic cops park by the side of the road and aim their radar guns at drivers passing by. As I demonstrated in “Here’s What You Look Like to a Traffic Cop,” drivers typically are obscured by shade and reflections off windows and windshields.

This is what most cars look like in broad daylight (photos taken on Patterson Ave. in Henrico County) from a vantage point on the sidewalk.

Visibility is even more obscured at night, and in cars with tinted windows.

Windsor police use RADAR and LIDAR technology to monitor vehicle speed, often from distances of more than 200 feet away. Police, said Rubin in a April 16 response to the Virginian-Pilot that Harki declined to include in his article, “are not aware of the driver’s race or sex until contact is made on the traffic stop.”

It is true,” Rubin said, “that once the officer approaches the driver, he can identify the face and even decide whether to issue a warning or a citation.” But, as explained above, the traffic-stop data indicate that black and white motorists are treated almost identically in Windsor once pulled over.

Confirmation bias. As I argued yesterday in, “Journalism, Confirmation Bias and the Presumption of Racism,” confirmation bias is a phenomenon in which people seek information that confirm their views and downplay or ignore evidence that conflicts with it. Nowhere is this unfortunate habit more common than in journalism today, where the narrative of systemic racism has taken hold. Racism has become the default explanation for any statistical disparity between blacks and whites. Indeed, in the Virginian-Pilot article, racism is the explanation even in the absence of any statistical disparity. Driving-while-black has become part of popular folklore. Anecdotal stories based on personal perceptions are routinely used to affirm the truth of the narrative, while conflicting evidence is ignored.

The first anecdote cited by Harki describes how Nicole Papillion traveled U.S. 460 with her parents in the late 1980s and early ’90s while attending VSU. Harki devotes considerable ink describing their fears of being ticketed for driving while black. “And sure enough,” he says, when Papillion’s daughter got a car in 2013, she got stopped for tinted windows — even though, Papillion claims, the tint was legal.

“The area is known as a speed trap, but it’s not the same for Black People,” Papillion said. “It felt like they were picking and targeting because we are Black.”

That’s it? That’s evidence of racist cops? Years of driving up and down 460 by Papillion, her parents, and her daughter, and one traffic stop? Upon what possible real-world basis did Papillion feel like black people were targeted? The fact that her daughter was stopped for tinted windows? Even if the tint was within legal limits, as Papillion insists, how was the stop racist? It is virtually impossible for a policeman to identify the race of a driver in a vehicle with tinted windows, legal or otherwise!

The fact that Papillion’s daughter was stopped one time confirmed the driving-while-black narrative, while multiple trips of not getting stopped were ignored. Confirmation bias at work.

A different source, Stacey Jennings, claimed she had been stopped countless times since attending VSU in 2007. She is gay and is often mistaken for a black man. (The article does not make it clear how that is relevant.) Jennings said she began making her lighter-skinned girlfriend drive instead. There is no mention in the story of whether the stops were justified. Was she speeding? If she was speeding, upon what basis does she maintain that she was pulled because she was black, not because she was speeding? If she was not speeding, why is that not mentioned in the story?

And what kind of thinking was at work behind the decision to put Jennings’ lighter-skinned friend behind the wheel? That racist cops are less racist against light-skinned blacks, therefore less likely to pull them over?

In not a single anecdote recounted by Harki is there any tangible evidence that a source was pulled because he or she was black. Each of his sources believed their traffic stops were racially motivated, but not because of anything the police said or did. Harki and his sources appear to believe in a world in which white people don’t get pulled by police, don’t get ticketed, don’t have guns pulled on them, don’t get searched, and don’t get arrested, only black people do.

As Rubin asked in his response to Harki, “Did he look for any anecdotes from black motorists who said they were not harassed or whites who said that they were?”

The answer, of course, is no. Harki found what he was looking for.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.