By James C. Sherlock

I have watched the public sessions of the Governor’s Chronic Absenteeism Task Force.

The structure of the task force, and its proceedings, have been fatally flawed.

That panel has been dominated by the progressive worldviews of Attendance Works and FutureEd.

I offer as evidence the “resources” for the first meeting on October 24th. Every single one uses Attendance Works or FutureEd for its expert assessment.

Then consider the agenda, discussion guide and this slide deck used on November 7th to set the stage for deliberations.

Such meetings have not encouraged debate, but rather have seemed to suffocate it. The process as it exists seems destined to coronate failed progressive ideas.

Progressive pressure reached the point that a member of the panel, Dr. Keith Perrigan, Washington County Public Schools Superintendent and President of the Coalition of Small and Rural Schools of Virginia, on November 7th felt it necessary to apologize in advance for seeming to be an “ogre” to the rest of the panel.

Because he spoke in favor of enforcement of truancy laws.

The Task Force needs to change that environment and the makeup of the task force or they will get more of what Virginia has already experienced using progressive approaches: chronic absenteeism.

The scale of the problem. In Virginia in the 2022-23 school year, the parent or parents or guardians of 1,263,580 public school students each made decisions, or failed to make decisions, for or against sending those children to school on each of 180 school days.

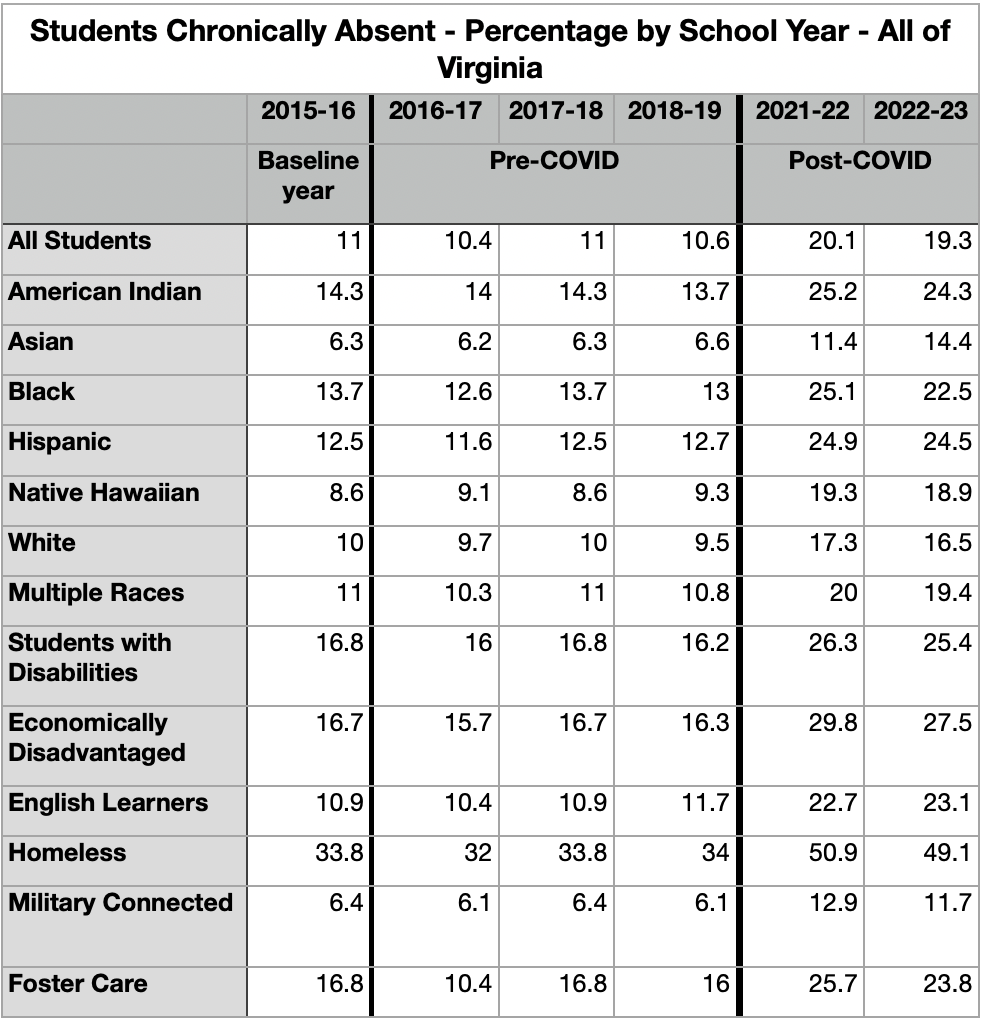

At the 19.3% statewide rate, nearly 244,000 of those kids were chronically absent – each missing more than 18 school days.

That defines the scale of the problem in the Commonwealth.

Each of those decision points that resulted in an absent child faced different types of issues.

- Value judgment. Did parents lose confidence in schools? Did they as a result value getting to their kids to school less than other things in the lives of themselves and their children?

- Impediments. Did they fail to get the kids to school because of something out of their control, like transportation or the health of the child or parent? Lack of clean clothes? Alcoholism? Drug addiction?

- Refusal. Did the child refuse? Did he or she refuse at a higher rate after Covid than before?

- Abuse. Was there something darker and illegal going on at home?

- Fear: Were they or their kids scared for their children to go to school?

Covid changes.

Chronic absenteeism, as seen in the spreadsheet above, doubled after Covid. And the absenteeism internal to those subgroups changed in lockstep. Why?

Certainly some of all of those five factors were in play. But they were all in play before Covid. So what changed? What will it take to fix it?

Much of the public discussion of the massive increase has been centered around:

- Covid broke generational patterns of going to school, and

- experiences during Covid lessened parents’ view of the value of schools.

Schools should not be expected to deal with those problems alone.

Schools doing more of what was done before Covid as recommended by Attendance Works, some of which may have been useful for other reasons but failed to change attendance patterns, is unlikely to move the needle in the right direction.

Dr. Frederick Hess. Someone of considerable gravitas in the field offers groundbreaking suggestions that the Governor’s task force must consider.

Those interested in this subject owe it to themselves to read Frederick Hess’ landmark article Education After the Pandemic.

Dr. Hess has a PhD and MA in government and an MEd in teaching and curriculum, all from Harvard. I am pretty sure the Harvard faculty broadly does not share his perspectives.

But his field and academic experience in education is broad, deep and distinguished.

What Works Clearinghouse. One of Dr. Hess’ observations is that waves of change from 2000 until Covid had no attendance impact.

That matches the results of the absenteeism intervention assessments of Institute for Education Sciences (IES) What Works Clearing House (WWC) reported here yesterday.

Hess is a big fan of IES, as I am, and wants to increase their funding.

“It’s also essential for funding language to make clear that funds are to be expressly directed to gold-standard learning science, not the mediocre ideological research that’s all too common in the field.” (emphasis added)

(No offense.)

Doing more of what was already being done to prevent absenteeism before Covid does not seem to Hess likely to meet the new challenges. Virginia’s experience suggests he is right.

Hess’ assessments of what to do are very much worth considering whether the reader, and the Governor’s task force, ultimately agrees with him or not.

He first offers detailed suggestions for improving both the inadequate teacher talent pool and technology assistance to teaching.

He then tackles real-world transformations.

“In practice, the web of rules and regulations, cultures and contracts, and policies and practices that entangle American schooling makes any kind of re-invention extraordinarily difficult.”

“When one considers the constraints imposed by collective-bargaining agreements, federal mandates, state assessments, parental expectations, and more, any talk of transformation can start to sound naïve at best.”

“While many of schooling’s familiar routines are the product of statute and regulation, others are the product of inertia.”

“Given that fact, it’s helpful to look at some practical ways in which policymakers, philanthropists, or tough-minded system leaders can start to move the needle.”

He offers recommendations for transformations of schooling to meet the new challenges. Paraphrased, they are:

- target the latticework of anachronistic routines;

- explore new staffing configurations;

- support schools of choice that emphasize innovation;

- stop asking local school systems to re-invent the wheel;

- start gauging education technology based on whether it makes it easier for teachers to teach well;

- embrace learning science (the IES section);

- insist on redesigned teacher roles as part of any deal to raise teachers’ wages;

- build ecosystems to tackle the chicken-and-egg dilemma of new roles. Schools can’t start redefining roles until people are trained for them, but it makes no sense to train people for positions that don’t yet exist. The best way to escape this impasse lies in building partnerships between training programs and a select few school systems.

Those are found nowhere in the newly revised Attendance Works/FutureEd Attendance Playbook. And they are unlikely to ever be seen there.

Playbook recommends more intense pursuit by overburdened schools of the same approaches that failed to improve attendance before or after Covid.

Sorry, but schools are stressed beyond limits.

Recommendation.

The Governor’s Task Force should reconsider its structure to entertain a different viewpoint than they have been presented to this point by asking Dr. Hess or a conservative of his stature to support its deliberations.

In upcoming parts I will discuss, among other subjects:

- the marketing challenge in changing parents perceptions about school. I will recommend the employment by the state of a professional marketing organization to create a campaign with regional and demographic group messaging to help deal with it. The schools cannot; and

- the question of who should investigate individual cases of chronic absenteeism and apply supports and/or sanctions. The schools have demonstrated they cannot (and many do not, at the advice of progressives want to) do that effectively. I will recommend the state Department of Social Services take over that job, including buying some of the time of school system support staff to assist.

Update: This was updated on Dec. 18, 2023 to align with this section of the book on this subject to be published before the end of the year. Some information was moved both to and from this section, but all of it was retained in the series.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.