by Hans Bader

Carjackings — especially carjackings by teens — have spiked in cities across the country over the past two years. NewsNation describes the “nationwide rise in carjackings”:

A pastor gunned down in a carjacking outside her home in Memphis. A thief runs up a driveway with a weapon drawn in New Orleans. An Atlanta mother of three, tossed out of her car and run over with it — all captured on her own Ring camera…Over the last two years, there has been a noticeable uptick in carjackings nationwide…

Chicago — a city with 40 cops on a carjacking task force —had more than 1,900 last year. That number is the most in the country and the most in the Windy City in decades…

And some of the perpetrators are shockingly young.

The pastor killed in Memphis was shot by a 15-year-old. In D.C, a 14-year-old was arrested for jacking six vehicles and trying to take a seventh.

Washington, D.C., reported 426 carjackings in 2021, up from 142 in 2019. This March, a Washington doctor was run over and killed by a carjacker who drove off in his car. Last March, two teenage girls aged 13 and 15 carjacked and killed an Uber Eats Driver in Washington, D.C., a crime for which they received only juvenile detention, not prison.

Carjackings are occurring across America at an alarming rate. On Thursday, a 13-year-old carjacker nearly killed a woman in Chicago while robbing her of her car while two little kids were in it, reported WGN TV:

A 13-year-old boy allegedly carjacked a woman working as a delivery driver Wednesday while two small children were in her car…

The teen struck the woman with the car as he fled the scene, police said. A few moments later, he exited the car while it was still in motion, crashing the car blocks away.

The 13-year-old was charged with felony vehicular carjacking and aggravated use of a deadly weapon.

On July 11, Chicago police arrested an 11-year-old boy for attempted carjacking. Yahoo Finance reported that “Children around that age have been arrested in carjackings in Chicago in the past. Police Superintendent David Brown at a February press conference commented on the young age of people being arrested for carjackings, saying half were juveniles, ‘and many are repeat offenders.’”

WGN reported that 15 juveniles had been arrested in Chicago for carjacking “in July so far,” according to court records: “Police said many work in crews and some work with older suspects.”

Four months ago, The New York Times noted that carjacking became a fad for some teens during the coronavirus pandemic. Teenagers are stealing cars and then posting videos boasting about it on Tik Tok. To troubled teenagers, carjacking is cool:

“The internet just took over,” one 16-year-old boy at E.L. Haynes said. “Everybody tried to go viral, doing stupid stuff.”

The boy, who like other classmates did not want to be named, said that in the early days of the pandemic, he had heard that guys on the street were stealing cars to bring in some money. Then young people started doing it, he said, at first jumping into cars that were left idling and unattended and just driving around. Videos of these rides around the city started showing up on social media.

Before long, “carjacking became a sport,” said one community organizer. “A big bandwagon,” said another.

As John Sexton notes, there is another “factor that may be partly driving this: The suspects in these cases often get away with it. Even if they are caught, because they are so young the worst they are often facing is a few years in a juvenile facility.”

Earlier, CNN described “dramatically” increasing rates of carjackings across America:

Carjackings have risen dramatically over the past two years in some of America’s biggest cities.

Just outside Chicago, a state senator’s car and other valuables were taken at gunpoint in December, and a group of children, one just 10 years old, carjacked more than a dozen people. A rideshare driver being carjacked shot his attackers earlier this month in Philadelphia. Last March, a 12-year-old in Washington, DC was arrested and charged with four counts of armed carjacking.

“The majority of it is young joyriders. They’re not keeping the cars. They’re jacking cars to commit another crime, typically more serious robberies or shootings, or joyriding around for the sake of social media purpose and street cred,” said Christopher Herrmann, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “It’s a disturbing trend.”

Comprehensive national data isn’t available because the FBI’s crime reporting system doesn’t track carjackings. But large cities that track the crime reported increases in 2020 and 2021, especially as the pandemic took hold of the country.

Teenage carjackers face much milder penalties than adult carjackers do, especially due to recent criminal justice “reforms.”

Progressive prosecutors have reduced penalties for crimes by teenagers by refusing to try people who committed violent crimes at age 16 or 17 in adult court, even when they commit murder, robbery, or rape. So violent teens — even teenage serial killers — will not be held beyond age 25 in these jurisdictions, no matter how much harm they cause, or how many people they kill. Some will be released by age 21. Such short sentences result in higher juvenile crime rates and higher recidivism rates among juvenile offenders. As Peter Moskos notes, “Recidivism among 16-year-olds went up” when the age for being prosecuted in adult court was raised. The recidivism rate for 16-year-olds rose from 39% to 48% for offenses generally, and from 18% to 27% for violent felony offenses.

Left-wing prosecutors are also refusing to seek sentence enhancements mandated by state law, such as the longer sentences required for repeat offenders. Studies indicate that longer periods of incarceration deter many crimes from being committed by people who are not currently incarcerated; they don’t merely prevent people who are already inmates from committing more crimes — although they do that, too. For example, a study found that longer sentences deterred people from committing murder, robbery, and rape. (See Daniel Kessler & Steven J. Levitt, Using Sentence Enhancements to Distinguish Between Deterrence and Incapacitation, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper #6484 (1998)).

A 2008 Santa Clara University study found that longer sentences for three-time offenders led to “significantly faster rates of decline in robbery, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft,” even after controlling for pre-existing crime trends and economic, demographic, and policy factors.

Maryland and Virginia are similar in many ways. But Maryland has shorter sentences for criminals than Virginia. It also has a violent crime rate more than double Virginia’s. In 2018, Maryland had a violent crime rate of 468.7 per 100,000 people, according to USA Today, compared to a violent crime rate of only 200 per 100,000 in Virginia.

Virginia’s Fairfax County is quite similar to Maryland’s Montgomery County, Md. The two counties border each other, have similar economies, cultures, and demographics, and had a similar crime rate back in the 1970s. Yet by 2018, Fairfax County ended up with a violent crime rate less than half Montgomery County’s in the early 21st Century. Experts attributed that to Virginia’s tougher sentences and its abolishing parole for violent felons in the 1990s.

ABC’s channel 7 discussed this in 2019 in “Why is Montgomery County’s violent crime rate twice as high as neighboring Fairfax County?” Law enforcement sources attributed Montgomery’s higher crime rate to the fact “that the Maryland Judiciary is, generally speaking, more lenient on criminal defendants” and the fact that “Virginia has stricter laws on the books” and “harsh sentences,” which are “a huge deterrent” to crime. “Criminals know if you commit crime in Virginia you might get whacked, while in Maryland, you might just get slapped on the wrist.”

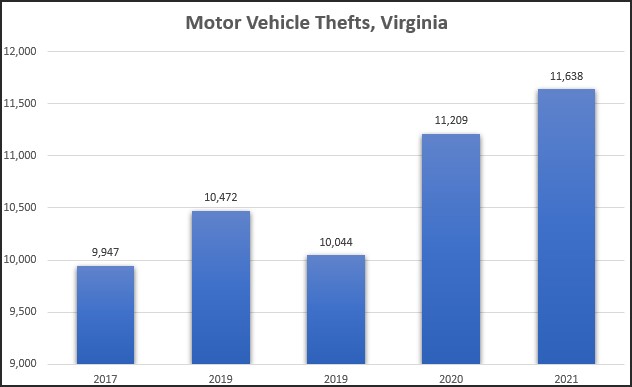

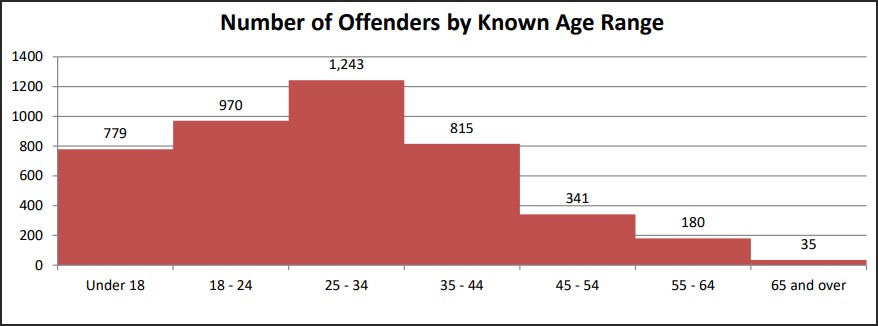

Hans Bader is an attorney residing in Northern Virginia. This column has been republished with permission from Liberty Unyielding. Bacon’s Rebellion has inserted the graphs based on Virginia data.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.