It can’t possibly get any crazier in Virginia. It just can’t. No satirist could dream up what now passes for news. On the front page of the Richmond Times-Dispatch today we see an extraordinary juxtaposition of stories:

- Sen. Majority Leader Tommy Norment, R-James City, was an editor of a 1968 Virginia Military Institute yearbook that featured “at least one” image of people in blackface as well as some racially offensive language. The T-D and the Virginian-Pilot, which broke the story yesterday, informed readers in breath-taking prose what they couldn’t possibly have imagined: that many Virginians were, by today’s standards, racist 50 years ago.

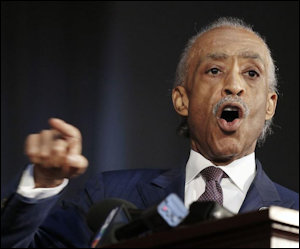

- Speaking at Virginia Union University, the Reverend Al Sharpton said there was no forgiveness for Governor Ralph Northam’s use of blackface in 1984 or Attorney General Mark Herring’s a few years before that. “If you sin, you must pay for the sin,” Sharpton said. “Blackface represents a deeper problem where people felt they could dehumanize and humiliate people based on their inferiority.”

In the fast-evolving canon of political correctness, not only was it racist to dress up in blackface 25 years ago (in Northam’s case), any remote association, no matter how tangential, with blackface a half century ago (in Norment’s case) appears problematic. Norment did not dress up in blackface. He did not take photos of people in black face. He did not post a blackface photo on his personal yearbook page. He was one of seven on the yearbook staff, and there is no evidence to indicate that he made the decision to include the black face photo (although there is no evidence that he didn’t). Further, deep in the article, it is revealed that Norment supported the desegregation of VMI, a controversial position for Virginia whites at the time.

While the media decides to make an issue of Norment’s tangential connection to blackface, the Times-Dispatch suffers a memory blackout in its account of the Sharpton speech. The reporter treats Sharpton’s moralizing without a touch of irony. Sharpton, who practically invented the term “race hustler,” is most famously remembered for his role in elevating the Tawana Brawley incident to national prominence.

For the benefit of journalists too young to recall the episode and include it as relevant background material, Tawana Brawley was a 15-year-old black girl in New York who was found unconscious, lying in a garbage bag, clothing torn, body smeared with feces. The words “KKK”, “nigger,” and “bitch” were written on her torso with charcoal. She claimed that she had been gang raped by six white men.

Sharpton and his colleagues picked up the accusation and made them a national sensation. Rather than treat Brawley’s claims with the slightest skepticism, they amplified them with wild allegations. As Wikipedia summarizes:

[They] said that officials all the way up to the state government were trying to cover up defendants in the case because they were white. They further asserted that the Ku Klux Klan, the Irish Republican Army and the Mafia were collaborating with the U.S. government in the alleged cover up. Harry Crist Jr., a police officer who committed suicide shortly after the period when Brawley was allegedly held captive, became a suspect in the case. Steven Pagones, an Assistant District Attorney in Dutchess County, New York, attempted to establish an alibi for Crist, stating that he had been with Christ during that period of time. Sharpton [and colleagues] then said that Crist and Pagones were two of the rapists. They also accused Pagones of being a racist.

A jury subsequently found Sharpton liable for making seven defamatory statements about Pagones and awarded Pagones $345,000 in damages. The Tawana Brawley story is now regarded near-universally as a hoax. Unlike Northam and Herring, Sharpton has not acknowledged doing any wrong, and he has refused to apologize.

Remember, the Brawley racist fabrication started in 1987, separated in time by only three years from Northam’s use of black face. By any objective standard, the vicious, unsubstantiated accusations hurled by Sharpton were far more harmful — and motivated by far more racial malice — than Northam’s daubing his face with shoe polish when participating in a dance homage to Michael Jackson. Yet remarkably, the Times-Dispatch treats Sharpton as someone with the moral standing to cast judgments in matters of race.

As the blackface drama unfolds — especially as we are reminded of numerous celebrities appearing on movies and television in recent years — it is becoming increasingly apparent that the outrage over blackface is highly selective and situational, influenced by political and ideological considerations. Rather than celebrate the objective reality that there is less racism than at any time in America’s history (I’m not saying there is zero racism, just less racism), the black-face fixation is part of a larger effort to redefine racism in order to perpetuate racial grievance and political advantage. I’ll have more to say about that in the future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.