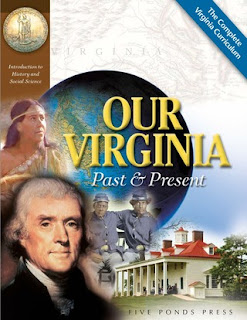

The controversies, of course, involve Connecticut-based Five Ponds Press, which has printed two textbooks for use in Virginia classrooms that contain a number of factual inaccuracies. The most serious was the racially charged claim that two battalions of African Americans fought under Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson during the Civil War. Others were simply stupid mistakes, such as getting the wrong year for America’s entry into World War I.

These errors do much to hurt Virginia’s reputation as a state for quality education as evidenced by top-ranked colleges such as the University of Virginia and the College of William & Mary.

They also show just how much the state Department of Education and local school boards have not kept up with the times.

According to the Virginian-Pilot, for years textbooks in the state were controlled by three big publishers — Pearson, McGraw-Hill and Houghton-Mifflin. The rise of Standards of Learning testing and the Net allowed new players, such as Five Ponds Press, to go after specific niche areas such as the state in the 19th century or special studies of select foreign countries.

New publishing technologies allow books to be easily printed in limited, to-order runs, as opposed to printing thousands of textbooks by the big players that update them periodically. It sounds like a modern and efficient way to disseminate critical information.

But it isn’t. As the run-up to the 2010 midterm elections shows, for example, there was all kind of nonsense out there on the Web. Unfortunately, Five Ponds picked up some bad, Web-based info, resulting in the textbook flap.

The spotlight, however, should really be on the state Department of Education, which approves textbooks (although localities have a lot of say in what they choose). The department claims that it lacks the funding to thoroughly vet textbooks. The vetting is done rather informally by teachers who come to Richmond once a year and, for a couple of hundred bucks, go through some of the 100 textbooks that are reviewed annually.

The big publishers do make factual errors, as well, but they tend to have deeper pockets and better fact-checking before they print and ship their products.

Del. David Englin (D-Alexandria) is introducing a bill that would remake how textbooks are reviewed, primarily by shifting fact-checking responsibilities from teacher panels to the publishers.

That might solve some of the problems, but the state still is responsible for checking the products it purchases. To do that will take money — certainly more than the pin money current vetting panels get. The state needs to better fund its fact-checking and make sure the people doing it are qualified.

But this is Virginia, after all, and it is hard to get past the “something for nothing” mentality that pervades state operations at every level. It is hard to spend to do anything from building a road to check a textbook. And you get what you don’t pay for.