If the threat of leaking coal ash pits kept you up at night, wait until you read, “Toxic Floodwaters: The Threat of Climate-Driven Chemical Disaster in Virginia’s James River Watershed,” a report just published by the Center for Progressive Reform.

Authors Noah Sachs (a University of Richmond professor and a friend of mine) and David Flores argue that the James River watershed “is among the regions of the country most vulnerable to the consequences of climate change” due to higher-than-average sea-level rise, intensifying rainfall, and increased hurricane risk. “As major storms cause serious and potentially toxic flooding in the James River watershed … residents are reminded that the industries surrounding them are not doing enough to plan and adapt to our changing world.”

Also, as we have come to expect from the modern environmental movement, there is a social justice component to the report. “Social vulnerability interacts with geography and climate to produce a climate crisis,” the authors write.

The study raises some legitimate questions, but I can’t find any evidence to buttress its strongest assertions. I’ll get to those reservations in a moment. But first, let’s see what the report says.

“Toxic Floodwaters” is the first comprehensive examination of the threat that storms and flooding pose to the socially vulnerable communities surrounding hazardous chemical storage sites throughout the Commonwealth, the authors write. The research project is the product of a three-year partnership between the Center for Progressive Reform, the James River Association, and Chesapeake Commons.

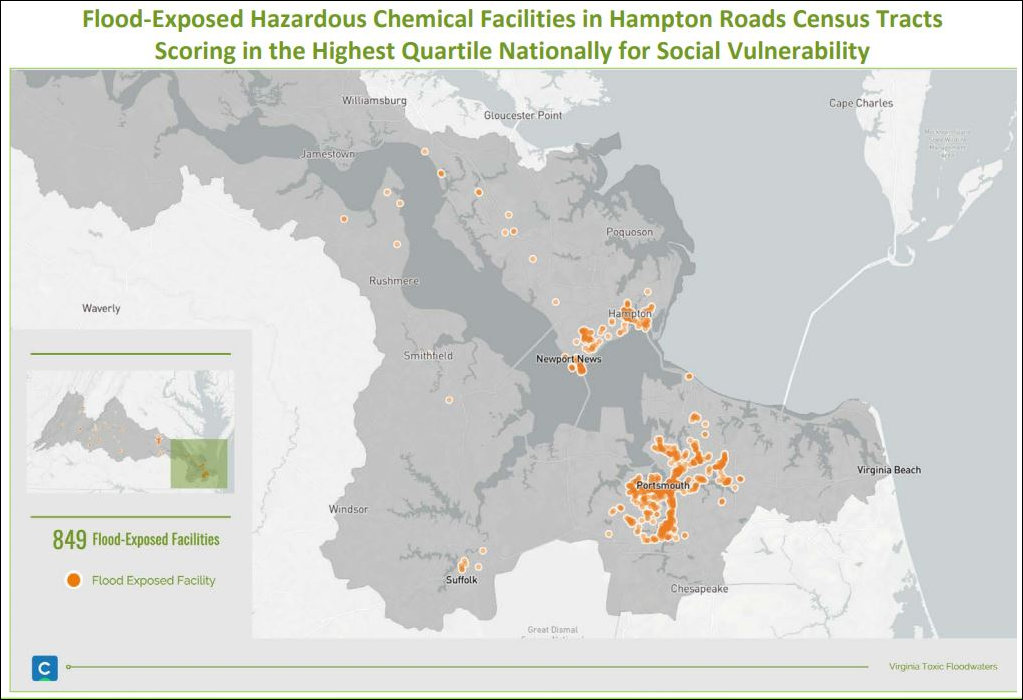

The three-part methodology of the study: (1) identified all industrial facilities in the watershed “likely” to handle toxic and hazardous substances; (2) created a geospatial model to map how these facilities are exposed to potential flooding; and (3) overlaid demographic data to identify census tracts that are most socially vulnerable to disaster events. The index includes metrics for vehicle access, crowded housing, age, education, English language usage, household income, and federal poverty status. Among the key findings:

- More than 2,700 industrial facilities regulated by federal and state

programs for toxic and hazardous chemicals are located in the most

socially vulnerable census tracts in the James River watershed. - In the tidal region of the James River, from Hampton Roads upriver to Richmond, 234 facilities regulated for hazardous or toxic substances would be flooded by future sea-level rise between one and five feet. Moreover, 91 of these facilities would be flooded by just one foot of sea level rise, which climate scientists expect to occur no later than 2050.

- On average, 125 socially vulnerable census tracts contain 25 flood-exposed industrial facilities each. Some 473,000 Virginians live in these census tracts.

Conclude Sachs and Flores: “Our research and analysis show that lawmakers and regulators in the Commonwealth have not effectively addressed flooding risks at industrial facilities – risks that are growing due to climate change.”

The study proposes a welter of new regulations to identify potential flooding risks, increase transparency, and tighten standards for siting, building and maintaining chemical storage tanks. “DEQ should realign its enforcement policy and invest new resources to prioritize inspection and enforcement efforts on flood-exposed facilities located near the Commonwealth’s most socially vulnerable communities.”

Bacon’s bottom line: Sachs and Flores have raised a significant issue that has so far eluded public attention. The risks they have identified are potentially of a magnitude that warrant closer scrutiny. The sea level is rising. Whether it’s rising as rapidly as climate-alarmist scenarios suggest is worth debating. Whether the risk of hurricane activity is actually intensifying is another empirical question that may or may not be substantiated by the evidence. But there is no denying the fact that, between sea-level rise globally and subsidence in Virginia’s Tidewater, water tables and the frequency and severity of flooding in the tidal reaches of the James River are creeping higher.

I’m not sure the social-justice angle adds anything to the debate, however. If there is a risk that floodwaters could be contaminated, does it really matter if a census tract is “socially vulnerable” or not? A threat to public health is a threat to public health. Are we now elevating threats to the “social vulnerable” population to a higher level of priority than to the general public?

My biggest concern is that the authors pre-suppose that there is a problem. As they write: “Residents are reminded that the industries surrounding them are not doing enough to plan and adapt to our changing world. … Our research and analysis show that lawmakers and regulators in the Commonwealth have not effectively addressed flooding risks at industrial facilities.”

Who says? They provide no evidence to back up that statement. They describe a hypothetical risk that bears looking into, but they over-reach when they assert definitively that the current regulatory regime is inadequate.

DEQ regulates and inspects chemical-storage facilities. “Toxic Floodwaters” provides no specific instances in which chemical and gasoline storage poses a tangible threat. The report provides no statistics on the number of inspections, much less the number of facilities that have failed inspection, nor does it critique anyone’s risk-management plans.

Sachs and Flores make the legitimate point that regulations should be forward-looking. Regulators should anticipate the elevated risk of flooding as the sea level rises in the decades ahead. However, in contrast to, say, coal ash, which has been buried in open pits through which rainwater and groundwater can migrates, gasoline and toxic chemicals used in industrial and commercial processes are stored in sealed tanks and containers. Moreover, the volumes are much smaller. Rather than talking about millions of tons, which will take years to remove, as with coal ash, we may be talking about millions of gallons or pounds. The logistical challenge of relocating chemical storage facilities as flooding risks increase in the years and decades ahead, I expect, is a fraction of that posed by coal ash. Even if the sea level is rising, one might conjecture, there is plenty of time for industry to adapt.

Still, I agree with the authors that transparency is vital. Citizens have a right to public records such as permit applications, inspection reports, companies’ risk-management plans, and compliance data. In particular, citizens have a right to know if risk management plans, which are updated every five years, consider the implications of sea-level rise. DEQ should make this information available online. Citizen activism is a safeguard against industry and government complacency. Perhaps a closer inspection of these records will expose real dangers rather than hypothetical ones.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.