During the COVID-19 pandemic educators did what they had to do in a short amount of time (five months in the case of Virginia) with little resources (extra funding came long after September of 2020) to keep kids learning through the 2020-2021 school year. A wholesale shift to remote and hybrid learning had never been tried before. Perhaps the challenge could have been handled better, but educators did the best they could under trying circumstances.

Rather than panic over the gap between the pre- and post-pandemic Standards of Learning pass rates, educators should focus now on catching up. The good news is that they know what they need to do, and they have many resources to get the job done.

Here is the bad news: teachers have only a finite amount of time to sequence what needs to be taught, and the scope of recouping lost learning is more than can be accomplished in one school year. Their job is made more challenging by the phenomenon of “spiraling” — in which a student must master one skill level before moving on to the next.

For example, in mathematics, the student first learns simple multiplication and then moves on to more complex multiplication.

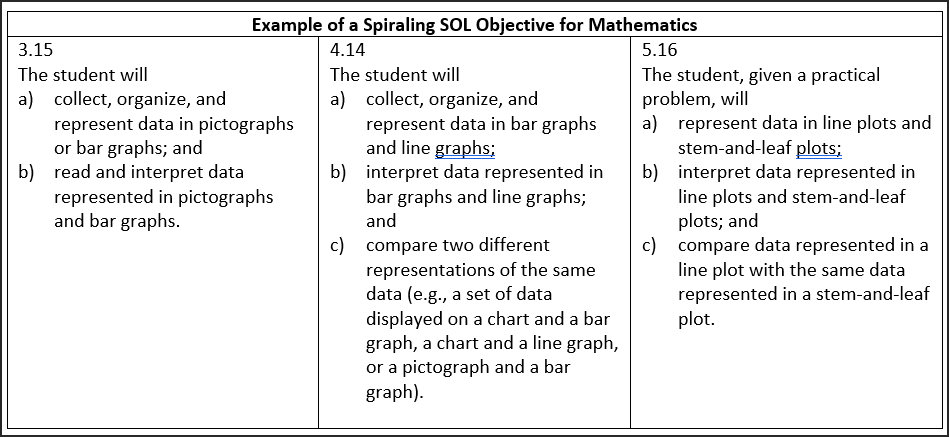

Here is an example from the SOL Blueprints for Mathematics, a tool that explains to teachers what objectives are tested and how many items are in each reporting category (available for every SOL assessment):

Post-pandemic mathematics scores plummeted. Thus, students who were at Grade 3 in 2018-2019 missed content in Grade 4 and Grade 5 in years 2019-2020 & 2020-2021, and suddenly, were tossed into Grade 6 in 2021-2022. There is a huge difference between Grade 3 content and Grade 6 content, and even more so between Grade 4 and Grade 7 content as demonstrated in the curriculum frameworks and test blueprints here.

Imagine being a 4th grader in 2018-2019 and then being provided 7th grade instruction in 2021-2022 if you had only received a cursory cover without needed mastery of the objectives in between? It would be like taking 1st year French and then going to 4th year French.

Similarly, students in Kindergarten, 1st grade and 2nd grade use the manipulation of concrete objects to understand math concepts. Students in these grades missed many classroom concrete learning opportunities.

For example, the teacher might give students a bag of mixed nuts to count, sort, and divide. This kind of learning is required for mastery at high levels and cannot be gained by simply telling a child how to sort. They have to “hold,” “touch,” and “feel” the sort. Sorts become more complex with each grade. For example, “big” vs “small” to “nuts that make sounds when they are shaken” vs those that do not. Both vocabulary and high-order thinking skills are developed in these grades.

In grades 3, 4 and 5, students are closer to thinking abstractly, but still need concrete manipulatives to solve more complex problems. Abstract thinking is a skill needed for 6th and 7th grade mathematics. Students who are not thinking abstractly will have more difficulty, for example, solving problems with negative numbers (Why does (-7) – (-10) = 3?).

Reading comprehension is dependent upon vocabulary development. Vocabulary development is dependent on two factors: (1) classroom instructional time where students are provided opportunities to learn new vocabulary; and (2) content vocabulary learned in science and social studies.

In many cases, teachers were struggling with covering the content in Reading and Mathematics, and, as an unintended consequence, Science and Social Studies might have been short-changed. Thus, SOL Reading scores showed a wider gap between non-disadvantaged and disadvantaged peers post-COVID as compared to pre-COVID, in some part, due to limited vocabulary instruction.

Was the learning loss so bad it can’t be recovered? Educators have begun the process of determining what needs to be done and are more than capable of meeting the challenge.

One approach is to cram more teaching time into the school year. Administrators are taking many approaches: adding 30 minutes of instructional time each day, providing after school programs, developing summer bridge programs, and trying countless other innovations to get more out of the instructional day. Even with these creative efforts, 180 days x the number of hours per day = a finite number.

Another approach is to equip teachers with more information about the students who are entering their classes. The Virginia Department of Education provides them an analysis of a student’s performance in previous SOL tests along with an analysis of their strengths and weaknesses.

Before politicians jump in with new laws to address the learning loss, let’s give educators a chance. Teachers have the knowledge, skills, and most of the resources needed to get the job done. Politicians may be able to fix things for future pandemics, but for right now, it is time to let educators do what they excel at — teaching.

Dr. Kathleen Smith is an educator living in Petersburg.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.