The Port of Virginia was the third largest East Coast port ranked by container traffic in 2010, with 11% market share. It trailed Savannah and New York/New Jersey, and Charleston was nipping on its heals. But the market for U.S. containerized cargo is forecast to double over the next decade, and Virginia’s ports are ideally situated to benefit from that growth.

In a presentation to the Commonwealth Transportation Board Wednesday, Jerry Bridges, executive director of the Virginia Port Authority, explained how the expansion of the Panama Canal would give Virginia’s ports a big competitive edge over its East Coast rivals. I have blogged on this topic before, but Bridges offered a greater level of detail.

The widening, expected to be complete by 2014-2015, will allow ships holding 18,000 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units, half of a standard shipping container) to use the canal. Currently, the canal handles ships with capacity of 4,400 TEUs. The use of larger ships will dramatically cut shipping costs from China, Japan and other Far Eastern nations to the U.S. East Coast, bypassing America’s West Coast ports and trans-continental railroads. (I could not attend the CTB meeting Wednesday, so I am basing this post upon Bridge’s PowerPoint presentation, filling in the blanks as necessary.)

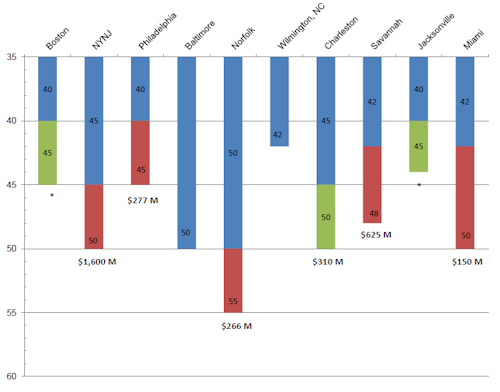

Other U.S. ports have limited options to expand capacity. Virginia has the only U.S. port with a permitted expansion project in place. Perhaps most crucial, Hampton Roads has the deepest channels of any East Coast port, meaning that it is best equipped to handle the giganzo container ships now coming out of the shipyards. The graphic below shows the current (blue), authorized (red) and desired (green) channel depths on the Atlantic coast.

Virginia also has partnered with the two East Coast railroads, Norfolk Southern and CSX, to upgrade rail routes emanating from Hampton Roads and Virginia by allow double stacking of container trains. The Heartland Corridor and National Gateway will connect Norfolk to the Midwest, while the Crescent Corridor opens up markets in the Northeast and deep South. Even though Norfolk International Terminals has added six new on-dock rail lines and doubled the capacity of its rail yard, the railroads aren’t expected to be able to handle the influx of traffic. Thousands of containers will have to move by truck.

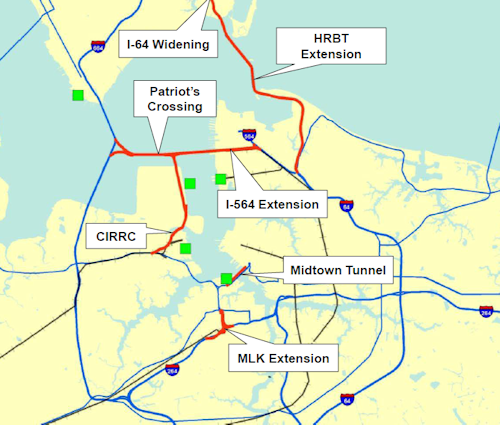

Freight movement has multiple highway bottlenecks due to the necessity of crossing bodies of water. The map below shows the port’s priority transportation projects in Hampton Roads. Not included here is the upgrade of the U.S. 460 link to Interstates 95 and 85 in Petersburg.

The Midtown Tunnel and Martin Luther King (MLK) extension are already funded. The other multibillion-dollar projects are not.

Two critical questions: First, how solid is the forecast showing a doubling of U.S. containerized shipments by 2022? What assumptions are embedded in that projection? Can international trade continue at the same rate as in the past three decades? What happens if, as President Obama hopes, an increasing share of manufacturing relocates back to the U.S. as China loses its edge as a source of inexpensive manufacturing? Is the forecast solid enough to base an investment of billions of public transportation dollars? And what happens to toll-driven projects if the traffic fails to materialize? I’m not doubting the forecast. I just want to hold it up to public scrutiny.

Second, if the demand is as powerful as Bridges says it is, and if the Port of Virginia will enjoy such an overwhelming competitive advantage in winning the growth in container traffic, why does the U.S. 460 upgrade need to commit $500 million in state subsidies? Do the three construction consortia bidding to partner with the state accept these port projections? If so, how much new truck traffic do they expect the port to generate? And why can’t they pay the full freight?

There are good reasons to believe that the Panama Canal widening will create a great economic opportunity for Virginia. Of course, the state should endeavor to support that opportunity. But I would like to see the analysis, if it exists, that justifies committing the state to a half-billion dollar subsidy.