by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon

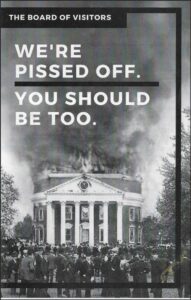

Earlier this month, an anonymous group distributed a pamphlet, “We’re Pissed Off: You Should Be, Too,” on the University of Virginia grounds that issued a broadside against the university’s governance structure. Although Board of Visitors member Bert Ellis was the primary object of their ire, the authors criticized the Board generally as “an undemocratic institution.”

“Seventeen people who are appointed by the State, which only provides 11% of UVA’s academic division’s funds, are deciding where 100% of it goes as the BOV gets the final say over approval of the annual budget,” states the pamphlet. “The Board of Visitors (BOV) as an institution is inherently undemocratic. It does not have enough checks and balances put into place to protect students, as well as faculty, staff, and UVA’s administration.”

This is a useful conversation to have. From the student’s or graduate student’s perspective, I suppose, the Board does seem undemocratic. Board members are appointed by Virginia’s governor. Neither students nor faculty get to vote on who serves on the board. But, then, the taxpayers of Virginia don’t get a direct vote either. Neither do parents paying tuition. Neither do alumni who collectively contribute as much to UVa’s funding as the Commonwealth of Virginia does. (Philanthropy and endowment income have surpassed state contributions as a revenue source.)

UVa, like other higher-ed institutions, is a strange beast. Its rules of governance are unlike those of government, or corporations, or charitable organizations. UVa is more like a feudal institution. It has an academic division and a healthcare division. The academic division has 13 colleges and schools, each with its own dean and varying degrees of autonomy and philanthropic funding. Students have a significant role in self governance. So do faculty. Affiliated with the university is a bewildering assemblage of autonomous groups that carry out important functions, each with their own boards.

Nominally, the Board of Visitors governs this feudal kingdom. But in reality it does not exercise much power. It is easily manipulated by the administration. This is not unique to UVa or a rap on President Jim Ryan. It’s the way almost all universities work.

Although the pamphlet was anonymous, the authors are likely associated with a particular group: the UVa chapter of the United Campus Workers of Virginia, a union that is organizing public college workers in Virginia. Most visibly, the UCW has led the campaign for a $15 minimum wage and has fought for the interests of underpaid graduate students. Demands for higher pay, a preoccupation with identity politics, and hyperbolic rhetoric — Bert Ellis is “a known racist, homophone, and bigoted asshole of a human being” — pervade the pamphlet.

The campus workers would do well to read up on the scholarly literature of university governance. A good place to start would be Runaway College Costs: How Governing Boards Fail to Protect Their Students by James V. Koch and Richard J. Cebula. Koch, incidentally, is a former president of the University of Montana and of Old Dominion University. The book draws heavily upon the public higher-ed system in Virginia and frequently cites governance practice at UVa. As you read the following quote, bear in mind that it comes from a former Virginia university president! (My bold face.)

Even though most college presidents use their charisma to accomplish mostly good things, the same charismatic qualities also enable them gradually to co-opt the members of their governing boards. Trustees are wined and dined when they come to campus; they receive choice football and basketball tickets along with great seats for lectures, performances, and other university events that pique their interest; they do not have to worry about parking tickets. They are made to feel they are vital cogs in an important phenomenon and are pleased when their successful president asks them what they think and on occasion implements their ideas. Skillful presidents orchestrate this scenario, whether or not they acknowledge doing so….

Most trustees buy into the president’s narrative about what the institution is, how it is ranked, and what it is attempting to accomplish….

Gradually, many board members evolve into partisans for their institution and president. Their fiduciary roles correspondingly recede, and they think not in terms of what is good for citizens, taxpayers, and students, but rather what is good for the corporate concept of the university as it has been defined for them by their charismatic president….

The board effectively ends up working for the president rather than vice versa.

Those generalizations arise from Koch’s lifetime of experience in academe, but they are generalizations. There are always exceptions. Do his observations apply to UVa?

In our observation, the answer is yes. That’s exactly how things work at UVa. The “We’re Pissed Off” authors complain that there are only four public board meetings per year, and that students are given an opportunity (as the result of recent legislation) of voicing their complaints only once a year, when the board is addressing tuition, fees, and other costs of attendance. The Board does have a non-voting student member who, ironically, was given extraordinary deference and enjoyed more speaking time this past year than any other board member, but the sense of powerlessness is understandable. Believe it or not, individual board members often feel powerless, too.

In our observation, UVa’s administration tightly controls the presentation of information to the board and controls the discourse. There is no wiggle room in board agendas for visitors to bring up new topics.

According to the board manual, “the Secretary shall prepare, under the supervision of the Rector and the President, a docket comprising such matters as the Board, the Rector, the President, and the chair of each standing committee shall refer for consideration.” If the rector and president don’t want to discuss something, it doesn’t get on the docket. There are any number of ways to bury an unwanted topic. A board member might be told, for example, to run it first through one of the six standing committees, where it can be bottled up or watered down. Or he or she can simply be given vague assurances that “we’ll deal with it,” and nothing happens.

Wide-ranging discussion also is dampened by packing the two-day board meetings with back-to-back presentations, often on inconsequential matters, and restricting discussion to the narrow topic at hand. The presentations take up most of the time allotted, leaving only a few minutes for questions. Schedules are adhered to rigidly. When time runs out, discussion stops, and the meeting moves to the next topic. There is no format in public board meetings for board members just to say what’s on their mind. (I have not attended the closed annual retreat so I cannot say what happens there.)

The administration also controls the flow of information. Aside from its massive PR apparatus, which packages the administration’s views in the form of news stories, photographs and videos on UVA Today, the administration selects the data it wants board members to see, it answers questions it wants to answer, and it ignores questions it wants to ignore. While board members typically do have a limited network of contacts from whom they hear differing views, they possess no independent source of data or analysis. Rarely do they have the ability to reality-check what administrators tell them.

The “We’re Pissed Off” authors are right, but for the wrong reason: UVa is not a democratic institution. But only on paper does the Board of Visitors sit at the apex of authority. The administration controls the agenda from start to finish; the function of the board is to apply the rubber stamp. If UVa’s unionized workers don’t like UVa’s priorities, they shouldn’t blame the Board of Visitors. They should blame the university’s leadership team: the president, chief operating officer, and provost. For the most part, with due recognition to the feudal nature of the university structure, they run the show.

In sum, what happens at UVa largely reflects the priorities of its top administrators — although outside groups such as the United Campus Workers on one side of the ideological spectrum and The Jefferson Council on the other do occasionally move the needle. To understand what happens at UVa, it is crucial to understand the hierarchical and oligarchical nature of the university. Captive to its woke, class-struggle schema for interpreting the world, the United Campus Workers don’t have a clue.

A goal of The Jefferson Council is to gain a keener understanding of how power and privilege are distributed at the University of Virginia, and whose interests are served by that distribution. More on that in future posts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.