Author Dale M. Brumfield’s new book chronicles the abolishment of Virginia’s death penalty.

Author Dale M. Brumfield’s new book chronicles the abolishment of Virginia’s death penalty.

by Peter Galuszka

Style Weekly

In 2015, Dale M. Brumfield, a veteran journalist and author, was finishing a masters degree in fine art in writing at Virginia Commonwealth University.

He learned of a prison inmate who escaped from Virginia to Florida, lived in a tent, and was caught after years of being on the lam.

“I got interested in talking to him for a story,” recalls Brumfield in his small office at his home in rural Hanover County.

The interview didn’t work out, but Brumfield says he got hooked on criminal justice and the death penalty. Not only did he write a book about the now-demolished Virginia State Penitentiary in Richmond, he became field director for Virginians Against the Death Penalty (VADP), an advocacy group that joined forces with other interested parties in abolishing capital punishment.

They were successful beyond their wildest dreams. In March of 2021, Virginia’s General Assembly voted to ban executions. It is the only state in the South to do so. “People had thought that this was far down the road. It caught everyone flat-footed,” he says.

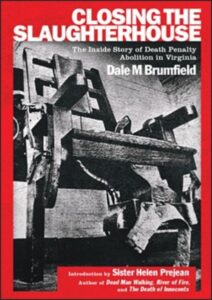

Now, Brumfield has written an important new book, “Closing the Slaughterhouse: The Inside Story of Death Penalty Abolition in Virginia,” that lays out the state’s dark and vast history with executions. [Full disclosure: Brumfield previously has written stories as a freelancer for Style Weekly.]

From 1608 to 2017, the state executed 1,300 people – more than any state. It leads the list in killing women (94) and enslaved people (736 or 87% of all executed in the country). The youngest victim, an enslaved girl named Rebecca, was hung in 1825 at age 10 or 11 for murdering a young girl.

Over the years, Black people were disproportionately hung or killed by lethal injection or in the electric chair. In colonial times, a Black could be hung for stealing a hog.

If a Black killed another Black, execution was unlikely, says Brumfield. But if a Black was accused of a capital crime against a white, especially a woman, it was an entirely different story.

Court trials sometimes lasted all of two hours with inexperienced defense lawyers before the ultimate sentence was passed. “Historically, the death penalty was used as a method to subjugate Blacks,” says Brumfield.

The 416-page book is deeply researched and a quick read. Brumfield says he drew on his research at VADP and spent days at the University of Albany, which has a vast database with details on executions around the country. “They have a wonderful digital database. (It has) every single execution complied by researcher M. Watt Espy. It’s incredible. It’s all online,” Brumfield says.

The book’s introduction was written by Sister Helen Prejean, a Louisiana nun who wrote “Dead Man Walking.” The popular book was made into a highly regarded 1995 movie starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn.

Brumfield researched his book and wrote it in a remarkable 14 months. He interviewed 50 people.

A key one was Joe Giarratano, a former scallop fisherman and junkie, who was a accused of killing two women and raping one of them in a Norfolk apartment in 1979.

An intoxicated Giarrantano turned himself in and admitted the crimes. He was sentenced to death but later the evidence did not seem clear. One of his obstacles was a peculiar Virginia law that gives a death row inmate only 21 days from sentencing to produce exculpatory evidence.

Giarrantano was scheduled to be electrocuted several times but finally, former Gov. L. Douglas Wilder commuted the death sentence to 25 years. Giarrantano studied law in prison, helped fellow prisoners and wrote widely, including an article for the Yale Law Review.

He was considered such a pest by corrections officials that he was sent to a prison in Utah and then says he received inferior health care when he arrived back in the Virginia corrections system. Poor medical care cost him a leg, Brumfield notes. He’s been released from prison and works in Charlottesville.

Giarrantano was a key witness in a jailbreak that involved Richmond’s notorious Briley brothers. Linwood Earl, James Dyral and Anthony Ray Briley went on an infamously brutal 1979 murder, rape and robbery spree in Richmond, killing 11 people, that involved firearms, knives and a cinder block.

In 1984, Linwood and James Briley were on death row at the relatively new Mecklenburg Correction Center that handled executions. They helped scheme a prison break involving four other inmates. The breakout caused a local news sensation. The two Brileys were finally captured in Philadelphia by heavily armed FBI agents and later executed.

At the time, Giarratano was also imprisoned at Mecklenburg. He was aware of the escape plans but opted to stay in prison. Several inmates protected captured prison corrections officers and nurses from harm.

Brumfield delves into what executions do to human bodies. It sometimes takes several jolts of power to kill a doomed prisoner. Their bodies have been known to smoke and catch fire.

He quotes Frank Green, a retired Richmond Times-Dispatch reporter who witnessed many executions. Green wrote of the electrocution of Robert C. Gleason Jr. in 2013: “He smiled, winked, and nodded at times towards his spiritual advisor sitting in the witness area. The smile was more of a leer, and the bravado came across as bizarre.

“His body tensed and his skin turned pink when the first cycle of electricity began. After a pause, a second ninety-second cycle was conducted.”

Lethal injections have had problems when the three-drug steps don’t work as intended.

There have been situations when death row inmates have been exonerated, which is one reason why death sentences can be suspect.

On July 18, 1943 in Petersburg, two police officers, Robert Hatchell and W.M. Jolly, pulled over a car with out-of-state plates they thought suspicious. The car sped away and crashed. A Black man jumped out and Jolly arrested two passengers in the car who claimed they had been picked up in Raleigh while hitchhiking.

Afterwards, Hatchell was found in a field wounded with a gunshot and soon died. It happened that Silas Rogers was hitchhiking nearby and the two car passengers claimed he was the killer. Rogers claimed he was on a northbound train at the time and was thrown off when he did not have a ticket. Later, Rogers confessed to the shooting although none of the fingerprints on the scene matched his. He was convicted and sentenced to death.

The questions surrounding his case attracted international attention. He even got support from James J. Kilpatrick, the hard right editor of the Richmond News Leader. Rogers was later released.

The fact that death sentences can be based on faulty evidence is one reason activists work to abolish executions. Another issue is that many convicts can be severely or mildly retarded and may not be reliable when interviewed by police or prosecutors.

That was the case of Earl Washington, Jr., who was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death for raping and murdering a woman in Culpeper woman in 1982. He spent 17 years in prison before being exonerated.

According to Brumfield, a key individual in the abolition movement and in Washington’s release was Marie Deans, who was involved in overturning the death penalty convictions of about 250 inmates, primarily in South Carolina and Virginia.

Deans died of lung cancer in 2011 but her work drew other advocates. One was Catholic Bishop Walter Sullivan of Richmond, who lobbied politicians and protested publicly against the death penalty. He and others frequently demonstrated outside prisons, notably Mecklenburg, where executions were to take place.

Brumfield joined the advocates as VADP field director and started lobbying, apparently not knowing that momentum was growing and a tremendous change was close at hand.

By 2021, a series of events set the stage for abolition. “It was a perfect storm,” Brumfield says.

Pro-execution stalwarts in the General Assembly started having doubts about executions. Twelve Commonwealth Attorneys in Northern Virginia sent out letters to their colleagues statewide asking that the death sentence be reconsidered, forcing an important prosecutors’ association to stay neutral, Brumfield explains.

Former Gov. Ralph Northam, reeling from his humiliation over allegedly wearing blackface in a medical school yearbook photo in the 1980s, started doing penance by meeting with Black community leaders. The feedback he got made him reassess the death penalty.

Another convert was State Sen. Richard Saslaw, a Democrat from Fairfax County. He had promoted the death penalty since the 1970s, but soon changed his mind after hearing from his constituents.

Then the George Floyd controversy and the Black Lives Matter drew considerable local, national and international attention. And state Democrats got control of the governor’s office and the General Assembly.

By March 2021, it had all fallen into place and the death penalty was abolished in an historic move. That’s when Brumfield decided to write his book.

He has resigned from being VADP field director after a three-and-a-half year run. “I guess I worked my way out of a job,” he says.

This book review was published originally in Style Weekly. It has been republished here with permission.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.