by James A. Bacon

The spread of smart phones and car navigators equipped with GPS technology is making it easier than ever to measure automobile traffic, and some transportation planners are putting the data to good use. In northern Spain, for instance, the Basque Traffic Control Centre is using GPS data from TomTom navigation systems to inform decision making.

TomTom has compiled the world’s largest car-centric database, containing more than six trillion individual points of data and adding five to six billion new measurements from customers daily. The Basques use the data to get real-time feedback on the effectiveness of traffic-calming measures such as traffic lights, speed bumps and roundabouts.

“The detail contained within the TomTom database has given us a much better insight into how our traffic schemes are working,” Ignacio Eguiara, head of Basque traffic investigation told ITS International. “We have been able to learn lessons that mean we are now able to plan new schemes far better and often more cost-effectively than before.”

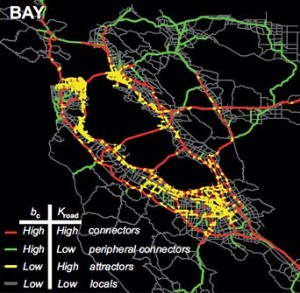

Using GPS data from cell phones, engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and University of California-Berkeley have found that drivers do not contribute equally to traffic congestion. According to the UC Berkeley News Center, canceling or delaying the trips of one percent of all drivers across a road network would reduce delays caused by congestion by about three percent. But canceling the trips of one percent of drivers from carefully selected neighborhoods would reduce the extra travel time for all other drivers in a metropolitan area by as much as 18 percent.

Said Alexandre Bayen, a Berkely engineering and computer science professor: “Reaching out to everybody to change their time or mode of commute is thus not necessarily as efficient as reaching out to those in a particular geographic area who contribute most to bottlenecks.”

Bacon’s bottom line: It remains to be seen whether this particular MIT-Berkely study will translate into changes in transportation policy, but it demonstrates the unprecedented level of analysis that GPS technology and massive data-crunching capabilities make possible. The information technology revolution is changing the rules of transportation planning.

The IT revolution is penetrating even the dark corner of Virginia, which under Governor Jim Gilmore had fancied itself the “digital dominion,” but, since then, seems to have abandoned any pretext of digital leadership. The newly opened 495 Express Lanes uses state-of-the-art traffic-monitoring technology to adjust its variable tolls. Of course, 495 Express Lanes is a private-sector venture. (I will profile the 495 Express Lanes control center very shortly and hope to visit the VDOT control center in Northern Virginia next month to get a better feel of how far IT has infiltrated the Virginia’s transportation sector.)

Meanwhile, Virginia’s political conversation about the need for new sources of transportation revenue — the only question asked is where to get the money, not how to invest it more wisely — seems oblivious to the technology tsunami rolling across the globe.

While the Basques race ahead, Virginians prattle about building a “transportation system for the 21st century” while investing billions in a transportation system that seems awfully reminiscent of the 20th. Our imaginations seem terribly stunted. Truly, the idea of building smarter roads rather than more roads should not be so hard to gasp.