by James A. Bacon

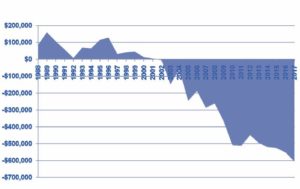

Once upon a time, the Highway Maintenance Operations Fund was flush with cash. Between 1986 and 2002, the Virginia Department of Transportation was able to transfer millions of dollars from the HMOF into the Transportation Trust Fund, which pays for new construction projects.

Those days are long gone. In Fiscal Year 2002, the Commonwealth Transportation Board approved the first transfer from the highway construction fund, $3.6 million, to the maintenance fund — a practice known as crossover. Since FY 2008, crossover transfers have averaged $418 million annually. Transfers are projected to increase to $600 million yearly by 2017.

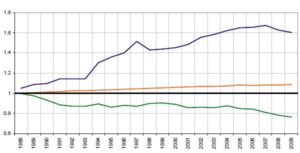

Growth trends: vehicle miles traveled (blue), lane miles (orange) and motor fuel tax revenues (green) in 1988 dollars.

Basically, there are two reasons why crossover is necessary, Jose Gomez, director of the Virginia Center for Transportation Innovation and Research, told the CTB during a strategic planning session in Portsmouth last week. First, revenues from the motor fuels tax has been steadily eroded by inflation in the price of asphalt and other construction materials. And second, Virginia’s highway system is aging and requires increasing maintenance resources to keep up.

Here are some of the scary numbers he presented:

- 1,116 lane-miles of interstate highways are in poor condition.

- 5,032 lane-miles of primary highways are in poor condition.

- 27,166 lane-miles of secondary roads are in poor condition, or 34% of the secondary system

- 1,730 bridges are structurally deficient

Looking ahead, 4,600 structures are in danger of becoming structurally deficient within the next five years, and an increase in Vehicle Miles Traveled (only temporarily in abeyance since the recession) will add to the wear and tear on the system.

For solutions, Gomez didn’t have much to offer. Eliminating the practice of taking subdivision streets into the secondary road system would save about $1 million yearly, he said. But even after 10 years, that would save only $10 million a year, a tiny fraction of the sum needed. Another option is devolution: transferring responsibility for secondary roads to localities. But politically, that’s a non-starter because localities are convinced that VDOT will not provide them with enough money to maintain the roads properly, much less to whittle down the backlog of bad pavement and structurally unsound bridges. Until VDOT can afford to pay more, it will be stuck with the secondary roads.

There was widespread sentiment among CTB members that the transportation system simply needs more money, but that belief was coupled with an acknowledgment that their job was to work with the resources they had, no matter how meager. Concrete ideas were in short supply. In fact, about the only proposal of any kind came from L. Aubrey Layne, Jr., an executive with Great Atlantic Management in Virginia Beach, who asked, “Do we have the ability to shrink the system?”

No, came the answer from Rick Walton, VDOT’s chief of policy and the environment. The state cannot abandon a road unless it can show that a public necessity no longer exists. As long as a single family depends upon a road, it’s practically impossible to shut the road down.

The strategy session ended without any meaningful proposals to emerge from the group. But Transportation Secretary Sean Connaughton closed with an important point. “If people admit it or not, we’ve … de facto devolved the system.” If counties want to build more secondary roads, they’ll have to foot the tab themselves. “There has to be a major reform of the program.” What that reform might be, he did not say.

This article was made possible by a sponsorship of the Piedmont Environmental Council.