by Matt Hurt

Twenty five years ago, the demand for teaching positions was not sufficient to supply the employment needs of newly-minted teachers. It was common in many divisions for teachers to serve for at least a year or two in an hourly instructional aide position before finally earning the coveted teaching contract. For whatever reasons, the teacher pipeline has dwindled to a trickle, and divisions can no longer be as particular when hiring teachers. If the candidate has a pulse, passes the background check, and has a provisional license (or at least close to it), they’re handed a contract. In far too many instances, divisions cannot find enough folks who meet these basic minimum qualifications to fill all of their vacant positions.

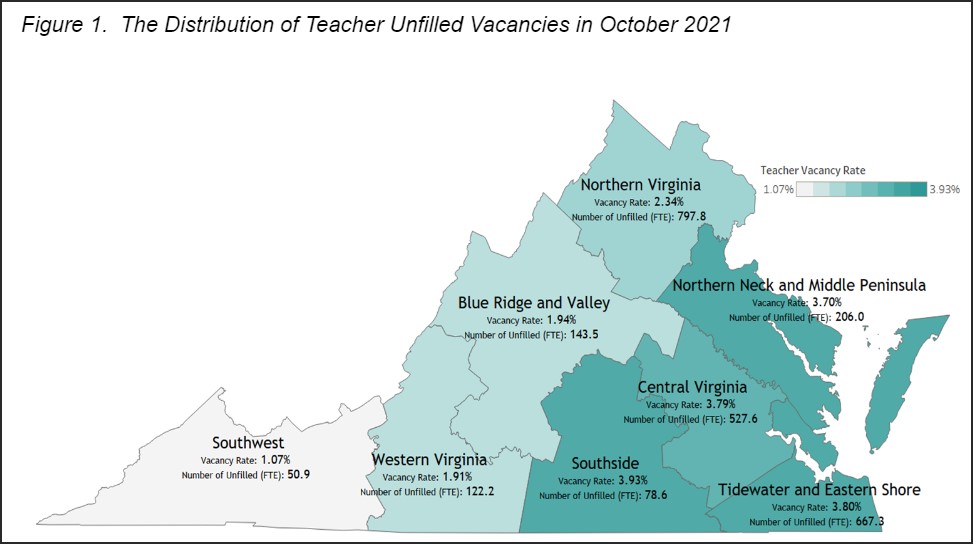

Many prerequisites must be in place to ensure positive student outcomes, not least of which is a teacher in the classroom. As of October 2021, 2.83% of teaching positions in Virginia remained unfilled, according to statistics conveyed to the Board of Education on September 15, 2022. The image below was shown to illustrate how the unfilled teacher positions were distributed throughout the state.

The Virginia Department of Education recently launched a new data tool (Staffing and Vacancy Report Build-A-Table) which allows anyone to view the number of positions as well as the number of positions that were unfilled at the time the data were collected. This tool should prove useful to track this problem over time, as well as to measure the impacts that this problem has on student outcomes.

Based on the statistics provided in the staffing and vacancy dataset as well as the SOL Build-A-Table data from 2022, there was a significant, negative relationship between those statistics. The rate of teacher vacancies accounted for 22% of the variance in SOL pass rates among the divisions in Virginia in 2022. This was greater than the relationships that many folks typically think impact scores the most, such as economically disadvantaged enrollment (18%), black student enrollment (17%), and white student enrollment (19%- positive correlation).

Given that it is statistically (as well as intuitively) consistent that fully-staffed classrooms ensure more successful student outcomes, it is important that we effectively address this issue. Unfortunately, this problem has two components, which makes it more difficult to deal with. First, there are fewer candidates who choose to enter the field than before. Second, we’re really struggling to retain teachers who are already in the field.

Teachers and prospective teachers, like every other human, respond to a variety of incentives when making decisions. Unfortunately, I am not aware of any published statistics which explains the effect sizes of the incentive structures in Virginia, and I doubt that we could ever produce any that demonstrate a great deal of reliability. However, there are certainly a number of factors that very likely play a role.

First, salaries likely play a large role in attracting prospective teachers to the field and retaining those already in place. For whatever reason, it seems that the COVID pandemic has significantly drained the worker pool, and the demand for labor has skyrocketed. One can’t travel past more than two businesses before seeing a help-wanted sign. This labor market problem is a real issue in Virginia. For years, we have witnessed the stream of teacher candidates decline to a trickle in our teacher colleges. Since the pandemic, teachers have been leaving the profession in the middle of the year at a higher rate than before. It seems that they now have more opportunities in other fields than before.

When compared to every other state in the union, Virginia teacher salaries are the least competitive. When compared to average household incomes, Virginia’s teacher salaries are the most negative outlier in the country. For example, New York’s average household income is $199 more than Virginia’s. However, New York’s teachers earn on average $32,622 more per year. These figures suggest to me that New York is more likely to recruit and retain teachers than Virginia. In Virginia, there are much more likely other opportunities that are more lucrative than teaching.

A good example of this is when we compare highly successful schools to schools that are not fully accredited and are involved with VDOE’s Office of School Quality. The highly successful schools have significantly less difficulty filling vacant positions, as they have a waiting list of teachers from other schools who want to be part of their team. Those schools which are not fully accredited consistently have higher turnover rates, and unfortunately tend to have more unfilled positions. One of the reasons (aside from the additional paperwork and training required of schools not fully accredited) seems to be trust.

Highly successful schools trust their teachers to get the job done with their students. The expectation is to make their kids successful. In the other schools, teachers are not as likely to be trusted to make instructional decisions. They are expected to do as they’re told — use this resource, implement this strategy, etc. When a teacher from an unaccredited school goes to one of those successful schools, they gain that trust and are more successful.

Third, teachers do not go into teaching to get rich, but rather to ensure great outcomes for their students. In successful schools, the outcomes are better, so teachers gain a significant amount of personal satisfaction which seems to negate the lure of more lucrative opportunities elsewhere. In a struggling school, not only are teachers not making the money they could in other professions, but they’re also not producing positive results for their students. In these instances, many don’t have sufficient incentives to remain. They feel they aren’t making enough money, and they’re not making a difference with their kids, so why deal with all of this?

I have spoken with a researcher from a Virginia university who has been working on the issue of teacher burnout since the pandemic. He tells me that the biggest factor they have found is the loss of self-efficacy. In other words teachers feel like they aren’t being successful as was discussed in the previous paragraph, and thus leave the profession. Unfortunately, this study has not yet been released.

In conclusion, the rate at which we fail to staff our classrooms has a significant and deleterious effect on our student outcomes, and there seems to be no sign of this problem getting better. While it is difficult to measure the effect of different incentives to attract and retain educators in the field (and there are certainly more than were discussed in this essay) common sense tells us that the current conditions are not consistent with fully staffed classrooms. At this point, we have two choices — we can whistle by the graveyard as the problem worsens, or we can proactively improve the incentive structures to ensure a teacher in every classroom.

Matt Hurt is director of the Comprehensive Instructional Program, a coalition of non-metropolitan school districts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.