by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon

Tax subsidies for businesses locating in the proposed 55-mile Route 460 Corridor-Interstate 85 Connector Economic Development Zone could add up to $50 million over 2015 and 2016, if HB 1183 is passed into law. Remarkably, no one seems to be questioning the propriety of such aggressive use of the tax code to promote industrial development.

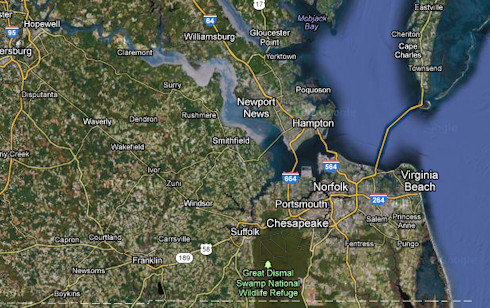

The bill would allow out-of-state companies to exempt taxes on income generated from activities within the zone, which includes the counties of Isle of Wight, Prince George, Sussex, and Southampton and the Cities of Chesapeake, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Suffolk, and Virginia Beach. Twenty-five percent of income would be exempted for companies employing at least 25 full-time employees, 50% for 50 employees, 75% for 75 employees, and 100% for 100 employees. Companies must be engaged either in maritime commerce or import-export manufacturing.

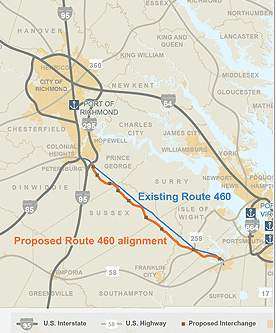

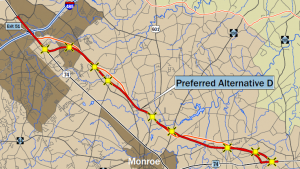

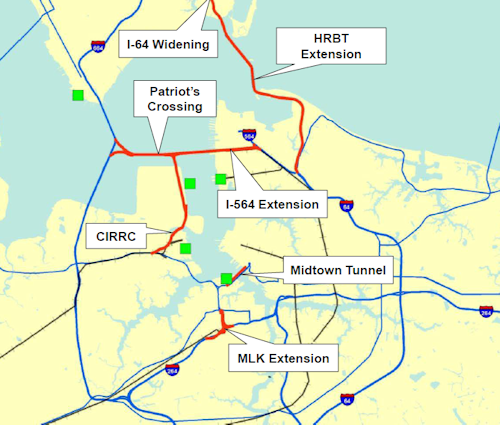

The bill, sponsored by Delegates Cosgrove, R-Chesapeake, and Bob Purkey, R-Virginia Beach, is part of a larger McDonnell administration initiative to stimulate commerce and manufacturing along the U.S. 460 corridor between Petersburg and Hampton Roads. (SB 578, sponsored by Sen. Frank Wagner, R-Virginia Beach, is the counterpart bill in the senate.) Gov. Bob McDonnell also has allocated $500 million toward the upgrade of U.S. 460 between Petersburg and Suffolk into an Interstate-caliber highway by means of a public-private partnership.

If Republicans want to establish their bona fides as fiscal conservatives, this is not the way to do it. Fifty million dollars in tax credits? No wonder tax revenues are stagnant — a multitude of credits, exemptions, deductions and carve-outs has shot Virginia’s tax code full of more holes than Bonnie and Clyde. If legislators want to subsidize corporate interests, then let them put a line item in the budget where it is highly visible to all. Don’t hide behind the tax code!

The General Assembly has already agreed to sweeten the pot of discretionary funds available to the governor to grease the skids for economic-development deals statewide. Now the governor needs more? Tax breaks for the Port of Virginia plus a 500 million state contribution to upgrade U.S. 460 isn’t enough? Surely the Governor’s Opportunity Fund should be sufficient to entice companies employing no more than 100 employees. It’s not as if we’re trying to land a new automobile assembly plant here — is it?

There are at least three points worth making.

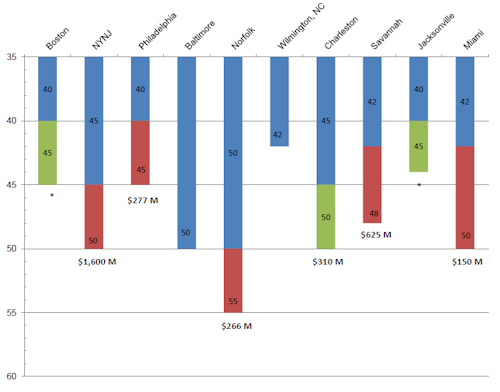

First, if the Port of Virginia is so well positioned to attract new cargo traffic when the Panama Canal widening is complete in two years, and if the state is already subsidizing construction of a new stretch of Interstate-quality highway, why do we need to subsidize corporate investment to the area? Is Virginia that uncompetitive?

One possible response is that other states are subsidizing new corporate investment, so we need to as well. That logic fails utterly, too, as I shall explain in the second point:

Do we really want to create an expectation among companies investing in Virginia that subsidies are there for the asking? That just encourages them to press for more, whether they need the assistance or not. The giveaways vitiate the fiscal conservative’s ideal of creating a level tax playing field for everyone. Our goal should be to make the tax base as broad as possible in order to set rates as low as possible. Tax subsidies may create short-term job gains — jobs that might have come to Virginia anyway — but they are the ruin of tax policy. The existence of tax loopholes keep rates higher, thus discouraging economic activity in sectors not favored by politicians. Trouble is, we never see the jobs not created, so we never know what we are losing.

Thirdly, the argument for subsidizing job creation ignores the impact of those jobs on the demand for infrastructure and government services in areas now lacking them. It’s one thing to land jobs in a population center like Norfolk-Virginia Beach where thousands of unemployed factory workers could be put back to work without relocating or straining public services. It’s another thing to bring the jobs to out-of-way places like Sussex and Isle of Wight counties.

Why do I mention Sussex and Isle of Wight? Because those are the counties where, according to a recent McDonnell administration-funded economic impact analysis, two new “mega manufacturing” industrial sites are planned. (See “U.S. 460 Project as Economic Development Powerhouse.”) The new manufacturing firms have the potential to support 2,635 permanent jobs directly and thousands more indirectly.

Perhaps someone deep in the bowels of the McDonnell administration has addressed the implications, but I have seen nothing. How well equipped are Sussex County (population 12,056) and Isle of Wight (population 35,457) to handle the influx of jobs and population? How much will the state have to spend on new roads? How much will the counties have to spend on new schools, utilities and public services?

Meanwhile, the McDonnell team would make matters worse with another piece of legislation that would capture new state revenue attributed to a transportation project, siphon it out of the General Fund and into the Transportation Trust Fund, and thus weaken the ability of the General Fund to pay for education, Medicaid, corrections and other things that only the General Fund can pay for.

This welter of economic development initiatives may burnish McDonnell’s credentials as “the jobs governor,” but it is not well thought out from a tax perspective. Virginia is becoming as bad as the federal government. We are creating so many subsidies and tax loopholes that it’s impossible to keep track of it all, much less to make economic decisions based on economic fundamentals. Conservatives have a name for this kind of boosterism. It’s called “industrial policy.” It is antithesis is small government and free markets.

Gov. Bob has aspirations, it is said, to be selected as a vice presidential running mate. Really? For which party?

Update: A reader reminds me that the Virginia Port Authority board agreed in principle back in September 2011 to chip in $5 million a year in state port funding to help pay for up to $250 million of the road. That would represent yet another subsidy, although a defensible one. The ports are the No. 1 beneficiary of the highway project and should be expected to contribute. Meanwhile, the Virginia Department of Transportation has applied for a $20 million federal TIGER grant and $200 million in federal TIFIA loan guarantee financing.