Last month the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) released its Nation’s Report Card, which showed that the average math test scores declined by eight points nationally. It was difficult for most Americans to know what to make of the loss. The scores were an abstraction. How bad was the loss of five points?

The Education Recovery Score Board, a collaboration between Harvard University and Stanford University, has devised an answer. Drawing upon the NAEP scores and standardized test scores from 29 states, the Harvard-Stanford team translated the drop in NAEP scores into years of education lost. The average U.S. public school student fell behind a half year in math, and a quarter year in English.

The Education Recovery Score Board performed another valuable service. Where the NAEP published state-average scores, the Harvard-Stanford project mapped the NAEP scores to the school-district level, providing greater granularity in the data and exposing wide differences between school districts within states.

“The pandemic was like a band of tornadoes that swept across the country,” said project co-director Thomas J. Kane. “Some communities were left relatively untouched, while neighboring schools were devastated.”

Judging by NAEP’s state-level data, Virginia got hit by more than its share of tornadoes. The decline in math scores between 2019 and 2022 was the worst in the nation, and in English almost as bad. But the Education Recovery Score Board data show enormous variability within the state. Some school districts survived with modest damage; others were flattened.

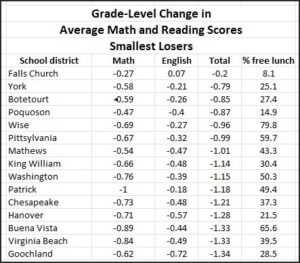

The cities of Falls Church and Poquoson and the counties of York, Botetourt and Wise survived the COVID pandemic in comparatively good shape, losing in the realm of a half year in math on average and two-tenths of a year in English — roughly in line with national averages. Falls Church actually saw a tiny gain in English scores — the only locality in Virginia to do so.

The cities of Falls Church and Poquoson and the counties of York, Botetourt and Wise survived the COVID pandemic in comparatively good shape, losing in the realm of a half year in math on average and two-tenths of a year in English — roughly in line with national averages. Falls Church actually saw a tiny gain in English scores — the only locality in Virginia to do so.

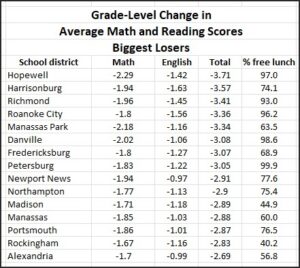

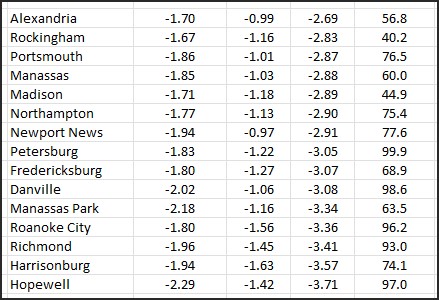

Conversely, the three years between 2019 and 2022 were catastrophic for the older, predominantly minority urban centers of Hopewell, Harrisonburg, Richmond, the City of Roanoke, Manassas Park and Danville. Those school districts lost roughly two years of ground in math and nearly a year-and-a-half in English.

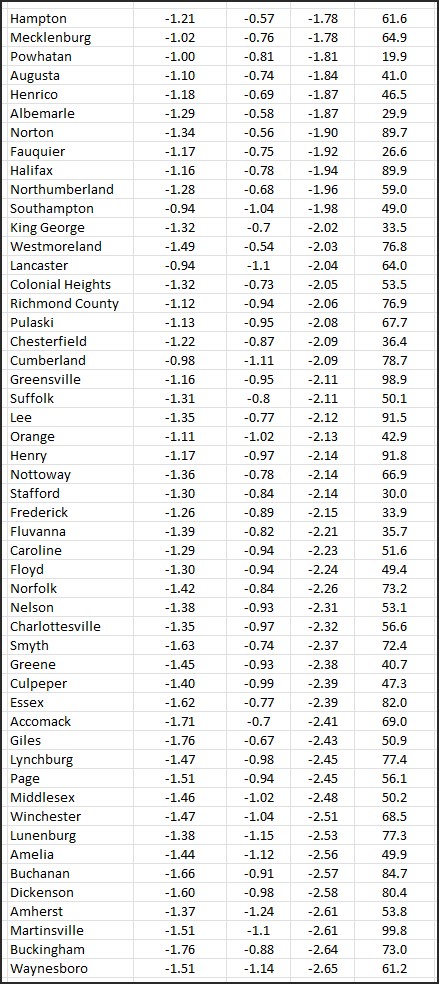

(Score summaries for all Virginia localities appear at the bottom of this post.)

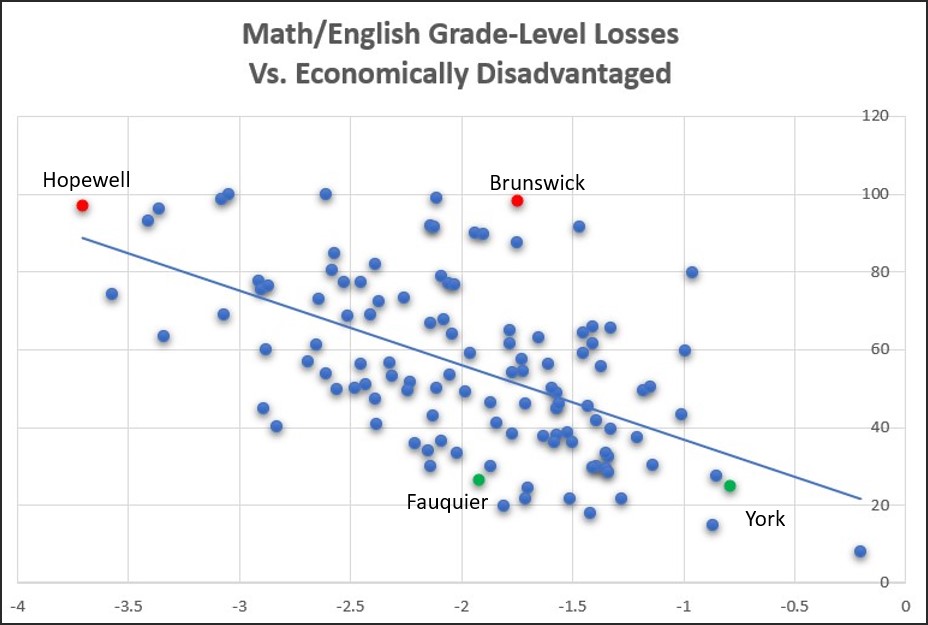

An interesting finding from the Harvard-Stanford exercise is the wide variability between school districts with similar socioeconomic profiles. Overall, school districts serving economically disadvantaged student populations (qualifying for subsidized lunch programs) fared worse during the pandemic and its aftermath than districts serving non-disadvantaged students.

That disparity comes as no surprise to anyone, as it has been replicated by state Standards of Learning (SOL) pass rates, early childhood literacy assessments, and other tests. Likewise, there is abundant anecdotal evidence to suggest that students from poorer neighborhoods had issues not only with Internet access but also with family situations — single-parent households in which that parent had to work — that resulted in desultory participation in online learning.

The trend line in the scatter graph below shows the significant correlation between “economic disadvantage” of district student populations (vertical axis) and the number of years of grade loss (horizontal axis).

Clearly, socioeconomic status is an important variable. Just as clearly, however, that factor accounts for only about a third of the variability. One might surmise that policies and practices of local school districts were equally important, if not more so.

For example, compare the two red dots on the graph: one representing Hopewell, a small city in the larger Richmond metropolitan region, and one representing Brunswick County in rural Southside Virginia. Both had very high percentages of lower-income students: Hopewell 97% and Brunswick 98.4%. But Hopewell experienced a total of 3.7 years of learning loss (2.3 years for math and 1.4 for reading) compared to only 1.7 total years of learning loss (1.2 in math and 0.5 in reading) for Brunswick.

It might be instructive to compare the respective approaches to education in Hopewell and Brunswick.

As another example, compare the green dots: Fauquier County and York County. Both are relatively affluent localities, with only 27% economically disadvantaged students in Fauquier and 25% in York. But Fauquier students lost 1.9 years combined in math and English; York lost only 0.8 years. Again, it might be worthwhile to compare and contrast philosophies and policies.

Bacon’s bottom line: The Harvard-Stanford project does nothing to contradict the Youngkin administration’s conclusion that catastrophic learning loss has occurred in Virginia. But it makes clear that the backsliding was far worse in some districts than others. School boards should take a look at their district’s relative standing to diagnose what went wrong, fix mistakes and share best practices for setting things right.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.