by Dick Hall-Sizemore

Probably the most important set of budget proposals made by Governor Youngkin for the upcoming General Assembly has been in the area of mental health. It has already been discussed generally on this blog. (See here and here.) It might be helpful to examine the details of the proposal.

The Governor, and others, have called his proposals “transformational.” That borders on the hyperbolic, but every governor engages in hyperbole in describing his proposals. His proposal actually accelerates a transformation begun several years ago, while placing additional emphasis on one aspect of government’s reaction to mental health needs—crisis management. Therefore, his description of his proposal as moving “from slow evolution to accelerated revolution” is entirely appropriate.

There is another aspect of the Governor’s proposal that is unusual and admirable—a three-year plan. Most Virginia governors wait until their second year in office and their first biennial budget bill before advancing any major initiatives. As a result, they actually have only a year and a half to implement it before leaving office. In contrast, Youngkin has proposed funding for the second year of the current biennium, to be followed up with additional funding in the 2024-2026 biennial budget bill. Therefore, his administration will be in a position to get the major components of his proposal well established during his term.

Background

A little background will probably help put the Governor’s proposals in perspective. In the simplest terms, mental health services can be divided between (a) inpatient services provided by traditional hospitals for the mentally ill and institutions for persons with developmental disabilities; and (b) outpatient services provided at the community level.

Up until about 50 years ago, the Commonwealth treated mentally ill persons only in residential facilities, such as Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg and Central State Hospital in Petersburg. Responding to advocates for the mentally ill, who contended that many individuals committed to the mental hospitals did not need to be institutionalized and, in effect, were being “warehoused,” the General Assembly, in 1968, created the community service boards (CSBs). These agencies, designed to provide mental health services to newly- “deinstitutionalized” individuals, as well as to persons needing outpatient services, were established at the local or regional level. The governing bodies of the agencies were appointed by the governing bodies of the local government or governments served by the CSB.

Funded by state appropriations and any local funding provided by their local governments, the CSBs were largely autonomous. By law, they were required to provide only emergency services and, to the extent supported by available funding, case management services. The state statutes did authorize CSBs to provide a wide range of services.

The services provided by CSBs varied widely throughout the state. For example, when asked about the degree of cooperation they got in providing mental health services to offenders on probation or parole, some chief probation officers had nothing but praise for the CSB in their jurisdictions, while other chiefs would say they got cooperation only grudgingly, if at all.

Most of the attention of the Dept. of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (DBHDS) and the General Assembly was directed at the residential institutions, because of their visibility and their problems. As their populations declined, some of the institutions were closed. Then, with the reform of the temporary detention order (TDO) and involuntary commitment laws in 2014, even more attention was paid to the hospitals as they began to fill up, and to individuals who needed inpatient services who had to wait for admission.

In the meantime, a major transformation in the delivery of mental health services in the Commonwealth was underway. It began with Governor McAuliffe’s budget proposals for the 2016-2018 biennium. As part of a settlement agreement reached by the Commonwealth with the U.S. Dept. of Justice over the delivery of mental health services in Virginia, he proposed appropriating $9.6 million over the biennium for crisis stabilization services. In 2017, McAuliffe and the General Assembly went further, enacting legislation that required all CSBs to provide an expanded range of services.

This new requirement for CSBs was called “System Transformation Excellence and Performance” (STEP-VA). It was to be implemented in phases. When fully implemented, each CSB is to provide the following:

- Same-day access

- Primary care screenings

- Outpatient behavioral health services

- Behavioral health crisis services

- Peer/family support services

- Psychiatric rehabilitation

- Veterans’ behavioral health

- Case management for adults and children

- Care coordination

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission has been charged with providing periodic reports on the implementation of STEP-VA. Its latest report can be found here.

In the ensuing years, the Governor and General Assembly have proposed, and provided, significant appropriations to implement STEP-VA, including the crisis services. In his outgoing budget, Governor McAuliffe proposed $5.5 million for the 2018-2020 biennium for crisis services. For the 2020-2022 biennium, Governor Northam proposed $50 million to implement STEP-VA, including the establishment of mobile crisis teams. In his outgoing budget for the 2022-2024 biennium, in addition to $50 million for implementation of the final phases of STEP-VA, Governor Northam included $24 million for the “continued implementation of the crisis system transformation” as well as $20 million in federal ARPA funding the first year.

Governor’s Proposal

Crisis Services

In his budget proposal, Governor Youngkin has chosen to focus on the front-end of the process—when people experience a mental illness crisis. Most importantly, responding quickly to these people can result in getting them the help they need and preventing their condition from deteriorating. Also, it can avoid their being placed in jails or committed to inpatient psychiatric facilities.

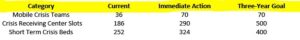

To its credit, in its summary of its proposal, dubbed “Right Help, Right Now,” the administration acknowledges the base that has been laid by prior administrations. Rather than build upon this base incrementally, as has been the practice in the past, the Governor is proposing to build the system out by the end of his administration. This chart shows the current number of facilities, the proposed addition (immediate action), and the goal at the end of three years:

To pay for these initiatives, the Governor has proposed the following budget amendments:

- Crisis receiving units and stabilization units–$58.3 million in the second year;

- Mobile crisis units–$20 million in the second year in one-time funding to contract with private providers.

The funding provided for the crisis receiving units and stabilization units will not be enough to reach the three-goal. Therefore, additional funding will be needed in the 2024-2026 biennial budget to be considered next session.

This proposal raises some unanswered questions:

Amount of funding–$78.3 million is a lot of money to dump into a system in one year. There is a question as to whether the system can effectively and efficiently absorb this sudden influx of funding. The location of all those receiving units, stabilization units, and mobile crisis units will need to be identified. Directors will need to be identified, facilities identified and rented, staff hired, equipment ordered, procedures developed, and coordination with local authorities (police, etc.) established. All this takes time. It is not known if the amount of funding provided represents the estimated annual cost or if the amount was calculated by building in the inevitable time lags. If all the funds provided cannot be spent in FY 2024, there is a general provision in the Appropriation Act that authorizes the Governor to reappropriate general fund balances.

Administration—In the past, appropriations for crisis services were made for grants to the CSBs. There was a general feeling by some budget analysts that CSBs were a “black hole” for appropriations because they were not accountable for how the money was spent. The new STEP-VA requirements undoubtedly have brought more accountability into the system. Nevertheless, as the JLARC report makes clear, some CSBs are more capable of implementing new programs than others. Although the main documents are not explicit, the underlying budget documents indicate that these programs will be contracted out by the central office. When asked who would have the responsibility for implementing these proposals, CSBs or the DBHDS central office, the folks in the Office of the Secretary of Health and Human Services did not respond.

One-time funding—The Governor’s budget document specifies that the $20 million for mobile crisis centers is one-time money “to contract with private providers to establish mobile crisis units in underserved areas.” This provision also raises questions. Why only one-time money? How will the on-going operating costs be funded? The Secretary’s office had no response to these questions, either. On the other hand, the $58.3 million budget request submitted by DBHDS for crisis services was comprised of $18.5 million in one-time federal COVID funds to be used for enhancements to existing crisis receiving units and stabilization units and $39.8 million in general fund appropriation. However, the Governor’s budget proposal was for $58.3 million in general fund appropriation, with no indication that any of it was one-time funding. (Admittedly, this analysis is getting into the budget weeds, but the details have implications for the following biennium and how much additional funding will be needed then. The money committees will be paying attention.)

Other services

In addition to the funding to expand crisis servicers, the Governor has proposed additional funding in the second year of the biennium to include the following:

- $15 million to expand the elementary, middle, and high school-based mental health program to additional school divisions;

- $9 million to expand tele-behavioral health services in public schools and on college campuses;

- $20 million for partnerships with hospitals for alternatives to emergency departments for crisis;

- $9 million for transportation and in-hospital monitoring by law enforcement and other personnel;

- $8 million for Serious Mental Illness housing, creating 100 new placements for SMI patients with extraordinary barriers to discharge;

- $15.1 million in general fund appropriation for 500 additional Medicaid developmental disability waiver slots;

- $41.6 million in general fund appropriation to increase Medicaid provider rates for agency- and consumer-directed personal care, respite, and companion services by five percent.

My Soapbox

Notwithstanding some pending questions, which, in truth, are more technical than substantive, Governor Youngkin deserves a lot of credit for taking on this issue that is important to a large segment of the Commonwealth’s population. The amount of money proposed is certainly important, but, perhaps more important is the focus of the Governor’s proposals—getting help quickly to folks undergoing a mental health crisis. That kind of help will save many people from having to undergo additional, deeper mental health anguish. It will have the additional benefit of long-term savings for the Commonwealth. If it can be implemented as planned, this proposal will be an important component of the Governor’s legacy.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.