By Derrick Max

Tuesday, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) warned that without substantially greater subsidies from DC, Maryland, and Virginia, they would be facing a $750 million annual shortfall that would require draconian cuts in services, including closing 10 stations, cutting 67 bus lines, and laying off 2,000 employees. They would also freeze salaries, raise fares and parking fees, reduce bus and train frequency, and close all stations at 10 p.m.

The threat of such cuts was meant to be a bargaining chip for more funding rather than a true plan to save WMATA, as any such cuts would just accelerate, not slow, the demise of WMATA. It is time for Governor Youngkin and the two other regional funders, all of whom are facing reduced federal aid in their own budgets, to seriously consider forcing WMATA into bankruptcy. And if WMATA’s unique structure as a bi-state compact agency makes it ineligible for Chapter 9 bankruptcy — a complete restructuring and rethinking of WMATA along a similar line as Chapter 9 bankruptcy are in order.

The truth is that bankruptcy is not a new idea. In 2016, WMATA hired one of the nation’s top bankruptcy lawyers, Kevyn D. Orr, to advise the agency on fixing its troubled finances. At the time, WMATA had a $1.8 billion operating deficit (a loss of over 200 percent of operating revenue) with $917 million in long-term debt (not counting pension and other benefit liabilities). The hope was that Mr. Orr’s expertise would help WMATA restructure its debt without resorting to bankruptcy, take a tougher line on labor negotiations, and wrest more money from the three Washington-area funding jurisdictions. Sadly, whatever reforms were implemented have had little, if any, impact on WMATA’s financial situation today.

Even before the pandemic, WMATA continued to run massive operating deficits. In 2019, the year before the pandemic, WMATA’s deficit had ballooned to 291 percent of operating revenue, and revenue from passengers had dropped to 25.1 percent of total revenue. Ridership had dropped in seven of the eight years before the pandemic. Then came Covid-19.

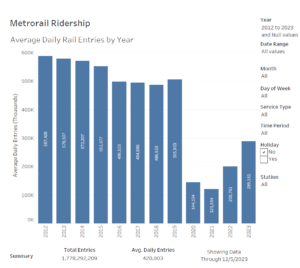

WMATA rail ridership dropped from 505,903 average daily rail entries in 2019 to a low of 121,544 in 2021. While WMATA brags that 2023 rail ridership more than doubled from the pandemic low, it is still only 289,151 daily entries now. For perspective, passenger revenue (both rail and busses) now only accounts for 4.8 percent of total revenue of $364 million, with expenses of $3.7 billion. Annual operating losses are now $3.3 billion or 916 percent of operating revenue. Debt has risen to $3 billion, again, before counting pension and benefit liabilities. This is not just unsustainable — it is a bankruptcy-level failure.

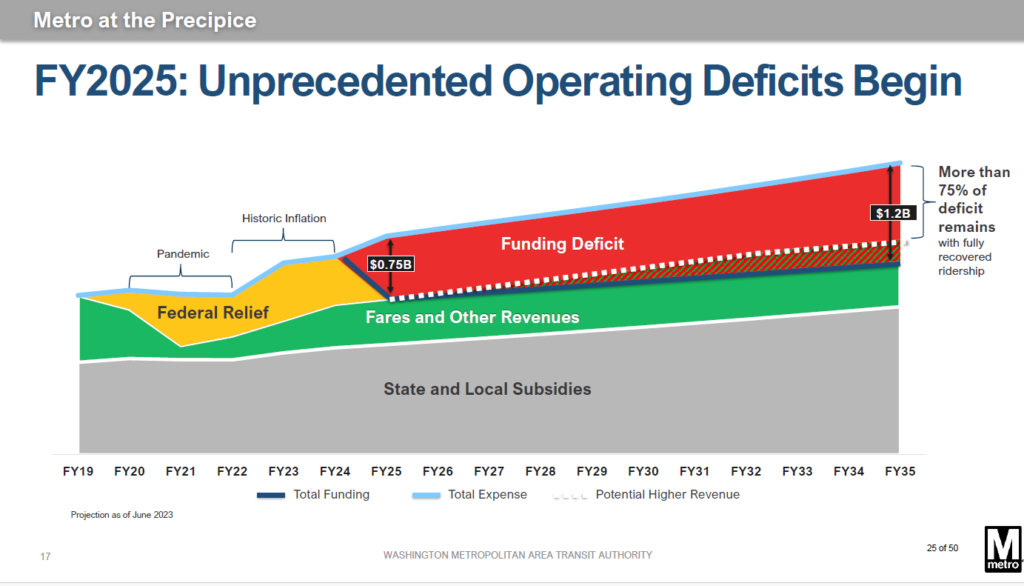

Of course, operating revenue is only a small part of WMATA’s finances. The vast majority of WMATA revenue comes from state and local subsidies. The best way to understand this is to look at a chart in WMATA’s planning document.

As you can see, WMATA’s operations have always relied on a growing base of government subsidies — subsidies that grew substantially during the pandemic (yellow Federal Relief on the above chart, plus the grey base). More interesting is that expenses barely went down during the pandemic, despite ridership collapsing. Worse, as the chart shows, due to the historic inflation of the last two years, labor costs (which under union contracts rise with inflation and currently make up 48 percent of WMATA expenses), grew by 20 percent over the last two years. This growth in wages will drive up expenses, as seen in the chart, and will carry forward indefinitely.

While Governor Youngkin and others have urged the Office of Personnel Management to issue a “return to work” order for Federal employees in hopes of driving ridership back up, as this chart shows, even if ridership returns to pre-pandemic levels, 75 percent of WMATA’s deficit will remain. In fact, you could double pre-pandemic ridership and WMATA would still be in financial deficit. Ridership was trending down before the pandemic, and realistically, the world today is far different. The odds of ridership hitting 2019 levels are very low. If you drew a trend line from the prior 8 years of pre-pandemic ridership, the 2023 level is only slightly lower than would have been expected absent the pandemic. It is also important to know that the miles of rail in WMATA have increased with the addition of phase two of the Silver Line, meaning ridership per station or per mile of track has tanked. WMATA has yet to learn it can’t build itself out of financial collapse.

Setting aside the growing issues of fare jumping, crime, broken 7000-series train cars, and resigning Inspector Generals — the issues with WMATA are far deeper than can be explained by those headline-grabbing problems. The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority is a failing institution in need of a bankruptcy filing if possible, or, at a minimum, a total restructuring.

At a minimum:

- WMATA must find authority to restructure its debts and negotiate new labor contracts which account for almost half of all their expenses;

- WMATA must shed its old management and start over with new leadership;

- WMATA must free up resources for greater innovation and restructuring in line with the post-pandemic transportation needs of the region (more buses, less trains?);

- WMATA must halt all expansion plans, like the tunnel to Georgetown and the Blue Loop that were designed for a different time;

- WMATA must take time to value its assets and ensure it is maximizing income from both operating and non-operating income;

- Any investments in expensive and unreliable electric buses and charging stations must be put on hold until the system can sustain the buses it has (it is a curious fact that the most recent study of Metrorail showed that its carbon-reducing benefits were outweighed substantially by the carbon expended to run the system. Metro stopped producing this statistic after the pandemic, as I am sure Metro’s carbon reduction estimates have crashed with reduced ridership).

Governor Youngkin, with his background in private equity, surely understands the power of bankruptcy as a means of saving important businesses. Let’s hope he applies this wisdom to WMATA before it is too late.

Derrick Max is President and CEO of the Thomas Jefferson Institute, which first published this yesterday.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.