by James C. Sherlock

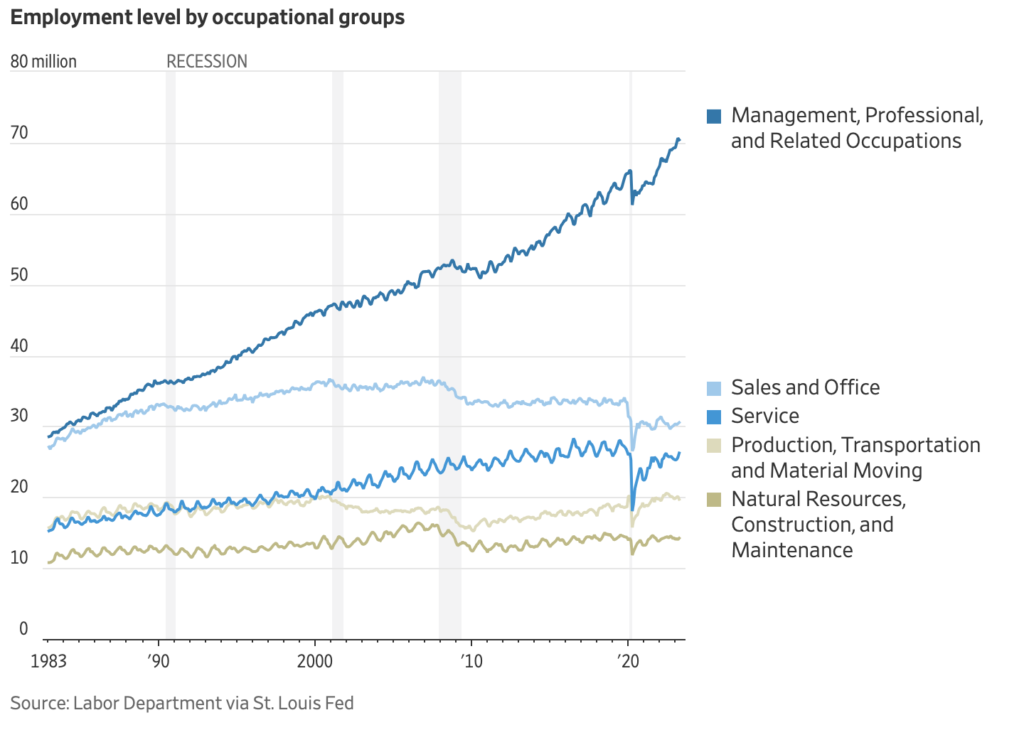

The chart above shows that management and administrative overhead growth has been a trend not limited to government. The difference is that corporations are making quick and decisive strides in reversing the trend.

It is axiomatic that government should minimize overhead to maximize efficiency in delivery of services. And to lower its costs.

Efficiencies need to be found:

- to maximize value for citizens;

- to speed decision-making;

- to minimize administrative consumption of the time and attention of front line workers; and

- to restore freedom of speech suppressed by government bureaucracies assembled for that purpose.

All senior government managers would sign up for those goals — as theory. But execution is hard. Internal pressures against change are seldom exceeded by external ones that demand it.

An excellent report in the Wall Street Journal makes an observation that they may wish to consult for inspiration.

Companies are rethinking the value of many white-collar roles, in what some experts anticipate will be a permanent shift in labor demand that will disrupt the work life of millions of Americans whose jobs will be lost, diminished or revamped partly through the use of artificial intelligence.

‘We may be at the peak of the need for knowledge workers,’ said Atif Rafiq, a former chief digital officer at McDonald’s and Volvo. ‘We just need fewer people to do the same thing.’

Corporate leveraging of technology.

Then comes the part to which government leaders need to pay close attention:

Long after robots began taking manufacturing jobs, artificial intelligence is now coming for the higher-ups—accountants, software programmers, human-resources specialists and lawyers—and converging with unyielding pressure on companies to operate more efficiently.

The marketplace is the source of that pressure.

Lyft, used in the Journal article as an example of corporate response to management and administrative bloat, just cut its numbers of management layers from eight to five. Lyft is a resource-light company — its drivers use their own cars — so the job trimming cut the company headcount by 25% in a single move.

Facebook parent Meta Platforms cut 21,000 jobs in six months. Again, about a quarter of its workforce.

How, other than the headline firings, are they lowering overhead?

- Many companies hiring white-collar workers are using contractors to fill their needs, freeing them to cut back as needed without staff rent-seeking and HR nightmares;

- Others, like McDonalds, are asking staffers to take pay cuts if they want to keep their jobs.

The applicability of all of those technology-enabled actions to government overhead reductions jump off the page.

The government of Virginia is relatively immune from market pressures, most often finding efficiencies only in response to lack of money. In the Great Recession, state government implemented unplanned personnel and pay cuts that were tactical, not strategic, and often unwisely distributed.

Government at all levels fails to match capital investment in information and process management systems acquired to increase efficiency with process, and thus staffing, changes. That means that the investment, even on the occasions that it brings improved customer service, does not capture value in reduced personnel costs.

The pressure senior government managers feel internally to maintain jobs comes from their own staffs.

In the corporate world that factor is overcome by competitive pressures across proprietary companies and IRS regulations limiting the overhead of non-profits.

At the colleges, is an underemployed deputy assistant dean or administrative staffer going to jump ship if a 10% pay cut is offered in exchange for keeping the job?

If they do quit, many will need not be replaced. Resignations from overhead jobs that need to be filled can be staffed with contractor-provided employees pending the implementation of more efficient technologies.

All of that can be done without changing the student-facing offerings and research efforts of those institutions, except to free their speech and inquiry and demand less of their time for endless meetings with layers of management and administration in support of issues that they either do not care about or personally oppose.

UVa. No other Virginia-funded college or university equals UVa, with its eleven-figure endowment to buffer bad management.

UVa has admitted publicly that it does not even know what many of its employees do. Or why they are paid what they are paid. Or whether a job in one department is really the same job as one in another department paid at a different rate.

The University has identified a couple of thousand such positions. In an attempt to gain staff participation in the sorting process, University leaders have promised no layoffs while they take several years in the attempt.

Easy prediction: some employees will work harder than they did at their actual jobs to never let them sort it out internally. External contractors will have to do it.

Bottom line. “We just need fewer people to do the same thing.”

But pressure will need to come from taxpayers and tuition payers to their representatives in the General Assembly and governor’s mansion for those savings to be realized in government.

For the most necessary government employees (think the nurses who inspect hospitals and nursing homes) part of the savings can be used to increase pay and fill the gaping vacancies in those critical jobs.

The best government workers will welcome increased efficiency to make their days more productive and thus more satisfying.

It should be hard to find a political divide in making government more efficient. The left will want the savings to expand the scope of government. The right and center will want the savings to decrease its costs and intrusion.

But I comfortably predict we will discover a divide in this matter nonetheless.

Quickly.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.