by James A. Bacon

One of the central debates about poverty in the United States has been the degree to which public policy should promote marriage. Children raised in two-parent families are less likely to grow up in poverty, goes the conservative argument. It’s not the marriage but the higher levels of education and income associated with marriage that make the difference, couner the liberals. (See my spin on a new reported issued by the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, “Who Needs Dad When You’ve Got Uncle Sam?“)

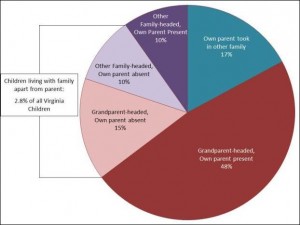

In an update to its original report, Weldon Cooper has published an amazing statistic: In 2011, one in ten Virginia children lived in a residential extended family — most often in the household of a grandparent but often with an uncle or aunt. These arrangements, which typically in response to a major life event such as a job loss, illness, divorce of break-up, are usually temporary. Half end within a year. Megan Juelfs-Swanson, author of the blog post and co-author of the study, acknowledges the value of extended families:

By banding together, the members of extended families pool economic resources, which may help to keep them above poverty. Furthermore, combined human resources can reduce other costs. For example, when grandma and grandpa watch minor grandchildren, it not only frees other members of the household to work but also eliminates the need for paid childcare. In these ways, extended families can act as a buffer against poverty.

But there are limits to what extended families can accomplish, the blog post says: “While forming extended families undoubtedly improved the economic conditions of some children, two out of five children in extended residential families live in households that struggle to make ends meet.”

Along those lines, the Times-Dispatch published a poignant story Sunday recounting the travails of two homeless Richmond teens who bounced between mother, father, aunts, cousins and grandparents, all with varying ability and willingness to care for them. Both teens rotated between relatives to spread the burden. The Richmond school system has identified enough children living this way — 34 at present — that it has developed a classification for them — “independent, unaccompanied youth.”

Although I disagreed with the thrust of the original study, I applaud Juelfs-Swanson for publishing this new data. It steers the debate away from simplistic discussions of the role of the nuclear family in combating poverty to a more complex, more nuanced discussion of the role of the extended family. Nuclear families — single mothers and their children — are embedded within a larger network of family relations. The debate about poverty needs to take that reality into consideration.