If you want a case study in why much of the public believes nothing emanating from the mainstream media, read The Washington Post’s latest smear job on the Virginia Military Institute. Staff muckraker Ian Shapira slams the Institute for the misogyny and sexual assault that he, like the Barnes & Thornburg report published in June, alleges to be pervasive there.

I shall delve into the particulars in a moment, but bear in mind a few key points. First, Shapira indicts an entire higher-ed institution on the basis of interviews with “more than a dozen women” who attend or attended VMI in the recent past and implies that their experience is typical. Second, he presents only their side of the story. Third, he does not quote a single woman who describes having had a positive experience at VMI, although there are many who would have gladly obliged. Fourth, he seeks to hold the VMI administration accountable for the fact that young adult males express misogynistic views — in other words, for the administration’s failure to function as thought police. Fifth, he omits statistical evidence showing that assault and rape are less prevalent at VMI than at other higher-ed institutions.

In short, Shapira’s article can be considered journalism only to the extent that he actually talked to some real people instead of making stuff up. His framing of a pre-determined narrative, his cherry picking of anecdotal evidence to support that narrative, and his exclusion of perspectives that would contradict his narrative (other than responses to specific allegations from VMI) can better be classified as propaganda.

Let us start by examining how Shapira presents data. “Fourteen percent of female cadets surveyed by the [Barnes & Thornburg] law firm,” he writes, “reported they’d been sexually assaulted at VMI and 63 percent said another cadet had confided being sexually assaulted.”

Sounds horrifying. Here is the critical context that he omits: In the largest-ever survey of sexual assault and misconduct on college campuses — 182,00 students on 33 campuses — the Association of American Universities found in 2019 that the rate of nonconsensual sexual contact was 26.4% for undergraduate women. In other words, the problem of unwanted sexual contact is ubiquitous on college campuses, as it is in American society (and most societies), but at VMI the incidence of such contact is half the rate (53%) that it is elsewhere.

Shoe-horning the facts into his narrative, Shapira recounts VMI’s resistance to admitting women until 1997 and draws a straight line to rapes and assaults that have occurred in recent years. He tells the reader next to nothing of what the administration does to combat sexual misconduct. Throughout the article, he is unable to distinguish between views expressed by immature male cadets on the anonymous Jodel social media app and the policies and practices of the academy’s leadership.

Let me be clear about one thing. I do not deny that rapes and unwanted sexual assault have occurred at VMI. Rape and assault, sad to say, are found on every college campus. Some men do terrible things. That’s why society enacts rules and laws to tame the savage beast.

The lower rate of sexual assault at VMI likely can be attributed to strict policies prohibiting the use of drugs and alcohol on post. There are good reasons for the prohibitions. One is that many, if not most, instances of assault and rape occur when one or both of the individuals involved are drunk. VMI is the only public higher-ed institution in Virginia where students can be punished for drug or alcohol offenses that come to light during a report of a sexual assault.

But rather than praise VMI for its strict policies on drugs and alcohol, Shapira implies that the Institute is not tough enough. During a series of annual dances held at the school, he says, students book up to 200 hotel rooms for raucous after-parties involving heavy drinking. To prevent drunken driving, VMI arranges shuttle buses and vans to ferry students between the dances and the hotels. A team of cadets roams the hotel hallways to monitor for public drunkenness and disorderly behavior.

“The alcohol-fueled parties have led to predatory behavior,” writes Shapira.

He proceeds to describe the experience of one woman who had gone to bed intoxicated and woke up with a male cadet she barely knew. Finding bruises on her hips, she suspected she’d been raped. The male cadet confessed to having sex with her but implied that the act was consensual. She couldn’t remember having sex, she thought, so how could it have been consensual?

That incident could have happened on any college campus in the country, where drunken hook-up sex, drunken regret sex, and drunken men-crossing-the-line sex occur with great frequency. These he-said/she-said incidents are difficult to sort out, especially when one or both of the parties were so blotto they can’t remember what happened.

The difference between VMI and other institutions is that VMI goes to greater lengths to curtail alcohol consumption than other universities, most of which take a laissez-faire attitude toward drinking. What is the alternative to VMI’s policy — to prohibit off-campus partying altogether? Does a higher-ed institution even have the legal right to do that? If so, does any institution have the means to enforce such a restriction? And is it not preferable to maintain a modicum of control? Shapira doesn’t bother with such questions.

Shapira also finds fault with the misogynistic attitudes of some male VMI cadets. VMI does conduct “extensive sexual assault training,” he quotes the Barnes & Thornburg investigation as writing, but male cadets “treat it as a joke and an opportunity for misogynistic humor, without consequence.”

When VMI issued a federally mandated Clery Crime Alert to the campus about a male cadet who allegedly “inappropriately touched several females” inside the barracks, Shapira adds, the incident became fodder on Jodel for sexist jokes about the “sheed didler.” (“Sheed” is short for “she-det,” or a female cadet.) Jodel commenters complained that men are presumed guilty, and went so far as to lament the presence of women at VMI.

Shapira provides no evidence that such thought crimes are any more prevalent at VMI than they are on other campuses, much less suggest what the administration is supposed to do about it. He does quote a VMI spokesman as saying that the First Amendment protects the speech on Jodel, and the anonymity of the app makes it nearly impossible to identify the students in any case. But such complexities do not dissuade him from his disapproving tone.

In a segue to the next anecdote, the WaPo writer says, “Comments denigrating women aren’t limited to Jodel.” He cites the example of a talent show in which a male cadet performed a stand-up comedy routine and joked about sexual misconduct at VMI. Once upon a time, making transgressive jokes about male-female relations was the stock in trade of comedians. But someone in the audience took offense and reported the routine to school officials. The student was punished: he lost his rank, was given a written reprimand, was confined to campus, and ordered to make penalty marching tours. Some students also took offense at the fact that the Commandant clapped at the end of the set. The Commandant was not disciplined.

This is remarkable stuff. What else was the administration supposed to do? Expel the student? Put him up against a wall and shoot him? For what — for triggering people with his offensive humor? The implication of Shapira’s tract is that the Institute should act to eradicate all politically incorrect thinking.

Shapira does recount episodes which, if fairly and accurately portrayed, would be considered deplorable by everyone. One woman described how an older student approached her from behind, kissed her and groped her butt and crotch against her will. Another woman described how she’d been raped by a friend she’d invited into her room to help with homework.

Yet another woman told of sleeping alone in her barracks room and waking up to find a student, Boris Rodrigo Lopez, in the room. She told him to leave, then fell back asleep. She woke up again to find him on top of her. She struggled and told him to stop. In this case, Lopez was arrested and criminally convicted. At his sentencing he said he couldn’t remember much about the attack because he’d been so intoxicated. That excuse did not get him off the hook. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

Needless to say, the administration did not condone those incidents. Still, Shapira quoted a few women as saying the administration had not done enough to help them and/or punish the men who abused them. Between 2017 and 2019, he writes, VMI reported 14 rapes, 14 incidents of “forcible fondling” and four cases of stalking. But how representative was the view that VMI could have done more? The Barnes & Thornburg investigators asked a survey question that Shapira did not deem worthy of including in his article.

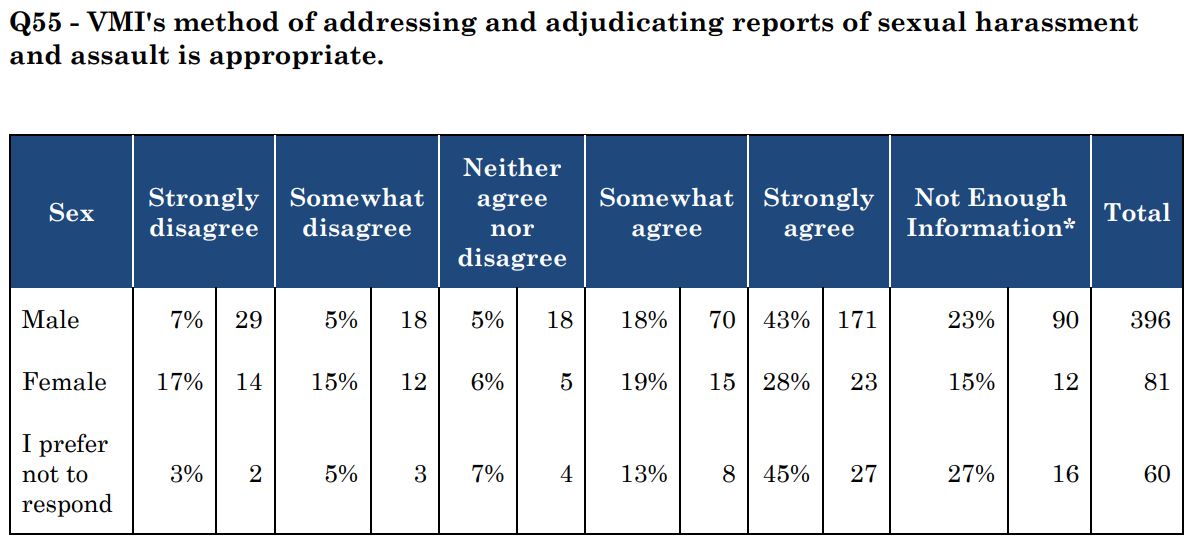

Thirty-two percent of female cadets disagreed somewhat or strongly with the statement that VMI’s approach to addressing and adjudicating reports of sexual harassment and assault are “appropriate.” But 47% responded that they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement. (Another 15% said they did not have enough information to make a judgment, and 6% were down the middle.)

In this anonymous survey, far more women supported VMI than disagreed with it. Shapira couldn’t bestir himself to quote a single one of those women.

I know for a fact that Shapira did talk to women who experienced sexual assault but did not fault VMI or the administration. I know because reports of Shapira’s inquiries filtered back to me. Despite his repeated unwanted approaches, multiple women refused to detail their stories – not because they were afraid of retaliation but because they did not want to talk about their experiences or because they did not trust him to tell their stories fairly.

These women expressed their concerns to VMI officials, family members and others that Shapira knew of their history as assault victims. They questioned how he had obtained their stringently protected personal contact information, including cell phone numbers.

Ironically, these women believe that Shapira harassed them through his multiple attempts at unwanted contact. It goes without saying that none of this appears in his propaganda piece.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.