by Dick Hall-Sizemore

by Dick Hall-Sizemore

The 2020 and 2021 sessions of the General Assembly enacted numerous bills that made it easier for citizens of the Commonwealth to exercise their right to vote. This article will outline the major changes, analyze their effects, and discuss efforts to repeal or modify these changes.

Following is a summary of the changes:

Voter ID

- Photo ID requirement eliminated;

- Voter must still present ID. In addition to the existing alternative forms of identification, driver’s license, DMV identification card, and student ID, the legislature added current utility bill, bank statement, paycheck, government check or other government document as acceptable forms of identification;

- Anyone not able to present any approved form of ID still allowed to vote, but must sign statement, under penalty of felony if false, that he is the named registered voter;

- Provided for DMV to issue identification privilege card that could be used as ID for voting.

Registration

- Provided for same day registration, effective Oct. 1, 2022;

- Authorized persons 16 years old or older who will not turn 18 before the next general election to pre-register. Required automatic registration of such person when he or she becomes eligible for registration or becomes 18 years old;

- For any person, who is an American citizen, performing any transaction at DMV, who does not exercise an option to decline, DMV required to forward the person’s name, address, etc. to Dept. of Elections who shall register person to vote, if not already registered.

Absentee Voting

- Provided for “no excuse” absentee voting;

- Allowed any voter to request to be on a permanent absentee voter list (used to have to renew annually);

- Registrar required to furnish postage prepaid envelope for return of absentee ballot;

- Required registrars to notify voters if affirmation not correctly or completely filled out and give voter chance to make corrections;

- Provided that any absentee ballot, postmarked on or before the date of the election, but received by the registrar after the closing of the polls and before noon on the third day after election, shall be counted.

Early Voting (voting absentee in person)

- Allowed absentee in person voting for anyone;

- Allowed localities to establish satellite office for voting absentee in person;

- Authorized registrars to provide for absentee in-person voting on Sundays.

Drop-Off Boxes

- Required drop-off location for absentee ballots at registrars’ offices, satellite offices, and polling places; and authorized the establishment of additional locations.

Virginia Voting Rights Act

- Prohibited changes to a “covered practice” unless it is indicated that the change does not have the “purpose or effect of denying or abridging the right to vote based on race or color or membership in a language minority group.” Local governing bodies are required to present any proposed changes to a “covered practice” in advance for public comment for a minimum of 30 days, with a 30-day waiting period following the public comment. There are five covered practices, which include any change that reduces, consolidates, or relocates polling places in a locality except in the case of an emergency; and any change that limits or impairs the creation or distribution of voting and election materials in any language other than English. Additionally, it empowers voters and/or the Attorney General to sue in cases of voter suppression. Virginia was the first state to pass such legislation.

EFFECTS

The original impetus for these changes was the need to make it easier for residents to vote due to the restrictions imposed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. However, because the changes were not enacted on a temporary basis, there obviously was a general desire by the Democratic majority in those two sessions to make voting more accessible and easier for more residents on an ongoing basis.

Although there have been only three general elections since the enactment of the changes—the 2020 Presidential election, the 2021 gubernatorial election, and the 2022 elections for the U.S. House of Representatives—it is not too early to draw some conclusions about the effects of these changes. Based on results so far, more people are registered to vote, a larger percentage of registered voters cast votes, and lots of voters chose to vote absentee. (All election and registration data used in the analyses that follow are derived from data on the Dept. of Elections website. The source of population figures is the U.S Census.)

Registration

The number of registered voters has increased each year. Increased population was one major factor in the increase. Another factor has been the presence of candidates who provide incentives to people, not formerly registered, to register and vote. Barack Obama and Donald Trump are prime examples.

There has been a pattern in registration changes. In a Presidential election year, there will be a surge in the number of registered voters. In the year following the Presidential election, there is usually a slight decrease, followed by modest increases or decreases in the next years before the surge in the next Presidential year. This pattern has resulted in an overall increase in the number of registered voters relative to the population.

To compare the growth in registered voters to the growth in population, it is best to use the estimated number of residents eligible to register, i.e., persons 18 years old and older. This number will be an inexact estimate of those eligible because it includes persons not eligible to register, primarily felons and noncitizens. Therefore, the estimated number of persons eligible to vote is overstated; therefore, the actual percentage growth in that population is probably lower than stated.

Keeping that caveat in mind, for the period 2010-2019, the Commonwealth’s population of residents eligible to register to vote was estimated to have increased by 8.6 percent, but the number of registered voters increased during that period by 11.8 percent. From 2019 to 2022, the proportional increase in registered voters was even higher. The number of persons eligible to register is estimated to have increased by 2.1 percent during that period, while the number of persons registered increased by 9.0 percent.

Voter turnout is usually expressed in terms of registered voters. Knowing how much of the state’s population is registered to vote can put the turnout numbers in perspective. The percentage of how many people eligible to register to vote who are actually registered has been growing in the last two decades. By 2019, the number of registered voters was 84.3 percent of the estimated number eligible to register. At the end of 2022, it is estimated that 90 percent of the eligible population in Virginia was registered to vote. This last increase in the number of registered voters, spurred by the presence of Donald Trump on the ballot in 2020 and aided by the legislative changes in 2020 and 2021, was a major factor in the large increase in turnout in the 2021 gubernatorial election.

Turnout

Historically, voter turnout in Virginia was low. That has changed in recent years.

Presidential elections—Since 1996, when the National Voter Registration Act (“Motor Voter”) was enacted, thereby significantly increasing registration, with a couple of exceptions, the percentage of registered voters voting in presidential years has hovered around 70 percent. The exceptions were 2000 (67 percent) and 2020 (75 percent). The increase in 2020 was probably more attributable to the presence of Donald Trump on the ballot than it was to the changes made in the laws regarding elections.

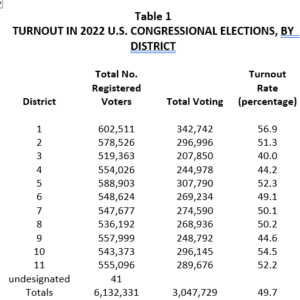

Congressional elections—The statewide turnout of registered voters in the 2022 elections for the U.S. House of Representatives was 49.3 percent. For the sake of comparison, one would have to go back to 2010, the most recent year prior to 2022 when there was not a statewide contest, Presidential, U.S. Senate, or governor, on the ballot with the candidates for House of Representatives. The turnout in 2010 was 44 percent, significantly lower than in 2022. It could be argued that the higher turnout in 2022 was driven by national publicity about whether there would be a “Red Wave” in which the Republicans gained a decisive majority in the House. However, only three districts in Virginia were thought to be competitive: the Second, Seventh, and Tenth. Yet, none of those districts had the highest turnout; that honor went to the First District, with a turnout rate of 56.9 percent. Furthermore, seven of the eleven Congressional districts had a turnout rate of 50 percent or higher. It would seem that the 2020 and 2021 changes that resulted in higher registration and made it easier to vote resulted in higher turnouts for what is usually a low-key election. The turnout rate for each district is shown in the table below:

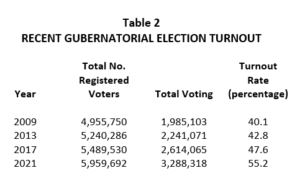

Governor’s race—The significant increase in turnout for the 2021 gubernatorial election, shown in the table below, is probably one of the clearest indicators of the effects of the changes in the law.

Absentee Voting

One of the areas in which the greatest change in law occurred and which showed the greatest impact was that of absentee voting. Based on the data so far, Virginia voters like being able to vote absentee, with about one in three Virginia voters not going to the polls on Election Day.

Prior to 2020, anyone wishing to vote absentee had to request a ballot for each election in which he wished to vote absentee. Furthermore, the Code specified a list of conditions under which absentee voting would be allowed, such as disability or out of town on business on Election Day, and anyone wishing to vote absentee had to qualify under one of those conditions.

The changes in 2020 did away with any required conditions and allowed any registered voter to request an absentee ballot without specifying any reason— “no-excuse” absentee voting. Also, it allowed any registered voter to request that his name be permanently included on the absentee voting roster, eliminating the need to request a ballot for each election. The prior year (2019), the law had been changed to allow absentee voters to cast their ballots in person, rather than mailing them, up to 45 days prior to the date of the general election. The cumulative effect of these changes was that any registered voter had a 45-day window in which to cast a vote. Coupled with the existing requirement that each registrar’s office be open the first and second Saturdays prior to Election Day and the authorization of registrars to open on Sunday, significant flexibility had been provided for residents to vote.

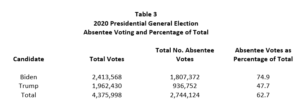

Prior to 2020, for non-Presidential years, the number of persons voting absentee, with one exception, was less than 200,000 and was often less than 100,000. In Presidential years, the number increased, especially in more recent years, to around the half million mark in 2008, 2012, and 2016. In 2020, after the changes in law were enacted, the number of absentee voters soared to 2.7 million, which was more than 60 percent of the total number of ballots cast. This large number of absentee ballots doubtless can be attributed largely to the effects of the pandemic and having Donald Trump on the ballot.

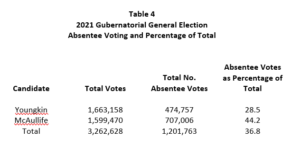

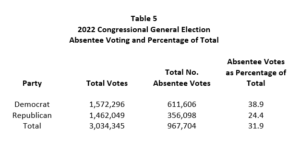

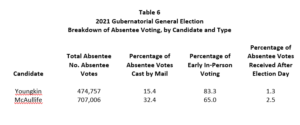

Even without the twin forces of the pandemic and Trump, more than 1.2 million voters voted absentee the next year in the gubernatorial race, constituting almost 36 percent of all ballots cast and almost one million voted absentee (approximately 32 percent of all voters) in the U.S. House races in 2022. (The Virginia Dept. of Elections considers voting in person early as voting absentee and reports mailed in absentee ballots and early in-person voting separately.)

The significant increase in turnout for the 2021 gubernatorial election may be attributable, at least in part, to the increase in absentee voting.

Breakdown by Parties

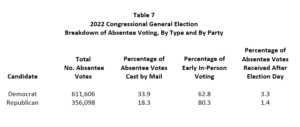

Both Democrat and Republican voters voted absentee. However, as with most political issues, there were differences between how Democrats and Republicans used absentee voting. (The data in the following analyses and tables are for the candidates of the two major parties only. Votes cast for independent and write-in candidates are not included.)

Absentee votes constituted a larger percentage of the total votes for Democratic candidates than they did for Republican, as shown in the tables below:

Both Democrats and Republicans were more likely to vote absentee in person than by sending in their ballot in the mail. However, voters for Republican candidates relied more heavily on the early voting than the traditional casting of absentee ballots by mail, with about 80 percent of those absentee votes being early in-person voting. The breakdown by type of absentee voting and party is shown in the tables below (the Dept. of Elections did not have the breakdown by type of absentee voting for the 2020 Presidential election):

Specific Areas

The foregoing analysis was on a statewide basis. It is likely that the legislative changes had even more marked effects on certain regions or populations. However, analyzing those effects at those levels would require a great deal of time, access to data that are not readily available, and probably more computer capacity than I have. That would be good topic for a senior or master’s thesis.

EFFORTS TO ROLL BACK CHANGES

In the 2022 General Assembly, Republican legislators introduced 30 bills to repeal or roll back the changes made in 2020 and 2021, or otherwise make voting harder. Most of the bills were killed in committee or, if reported by the House, were killed in the Senate. In the just-concluded 2023 Session, there was less activity—only 19 such bills were introduced, with four passed in the House, only to be killed in the Senate. In both years, the total included duplicate bills and overlapping bills. Furthermore, some legislators introduced more than one bill.

My Soapbox

I admit that I am something of a traditionalist. Many, many years ago, I was stirred by Theodore White’s description, in The Making of the President 1960, of election day. “They had begun to vote in the villages of New Hampshire, at midnight….” Voting then spread across the country “in schools, libraries, churches, stores, post offices…. All of this is invisible, for it is the essence of the act that as it happens it is a mystery in which millions of people each fit one fragment of a total secret together….”

The idea of citizens of a country or a state coming together on a single day to elect their leaders is romantic and inspirational. But, I have to admit, not realistic. Nor is it in keeping with the idea of a participatory democracy, in which the people who are being governed get to participate in choosing who governs them. Many people must work on Election Day and do not find it easy to get time off to vote. Others may find out a few days before Election Day that they must be out of town on that day or some other obligation looms.

Other than sentimentality, I do not understand why anyone would object to extending the time in which one has to cast a ballot. Nor do I understand most of the objections to other provisions intended to make it easier for folks to vote. Of course, those objecting to the changes usually raise the fear of fraud. However, there have not been any verified instances of anything more than an occasional instance of fraud, only allegations.

There is one hot-button issue on which I can see some validity—voter ID. Virginia does require that voters present some form of ID. Many legislators, however, want to require some form of photo ID. I think their fear is overblown, but it is not totally unreasonable. However, I have heard people more knowledgeable than I am explain that there are a significant number of residents, particularly older Black people, who do not have photo IDs. In order to have some idea of what effect a requirement for a photo ID would have, it would be helpful if the Dept. of Elections could provide data on how many people voted in the last three general elections while showing some ID other than a photo.

One of the new provisions that I have doubts about is the ability to vote absentee in person up to 45 days prior to a general election. Aside from it being foolish for one to cast a ballot that early because a lot can happen in the run-up to Election Day, I suspect that it is a waste of time and money. It would be instructive if the Dept. of Elections could tell us how many people voted in the first half of that 45-day period, together with the costs incurred by having registrars on duty during that period. I would think that a 21-day period before Election Day, coupled with a requirement that registrars stay open on Saturdays and, perhaps, one Sunday, during that period, would provide sufficient flexibility for everyone.

I am not the only one to advocate reducing the time for in-person early voting. Several of the bills introduced in 2022 and 2023 would have reduced this period. The Washington Post reports that a major Republican operative, in comments to attendees at a Republican National Committee donor retreat this week, focused on this issue, hoping for a Republican take-over in the Virginia legislature that could lead to the elimination of early voting. “Forty-five days!” she said in a reference to Virginia’s early voting period. “Do you know how hard it is to have observers be able to watch for that long a period?

The irony of this is that the 45-day provision for in-person early voting was enacted in 2019 when Republicans were in the majority in both houses of the General Assembly. Furthermore, one of the bills that contained the provision (HB 2790) was introduced by a Republican, Del. Nick Rush (Montgomery). It passed on strong bipartisan votes in the House (89-10) and Senate (34-6).

The staff at the Virginia Department of Elections provided invaluable assistance to me in my research for this article for which I am most grateful. They responded promptly to my seemingly endless questions, clarifying some of the data and pointing me to the location on the agency’s website in which I could find the details I needed. (That location is not obvious.) Just so there is so misunderstanding, I want to emphasize that much of the data presented, especially in Tables 3-7, is not set out on the website in that manner. I calculated the statewide breakdowns of the absentee voting, using data on the agency website. Consequently, I bear responsibility for those calculations, not the Department of Elections. Likewise, any conclusions are mine alone. The agency staff made no effort to influence this article.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.