by James A. Bacon

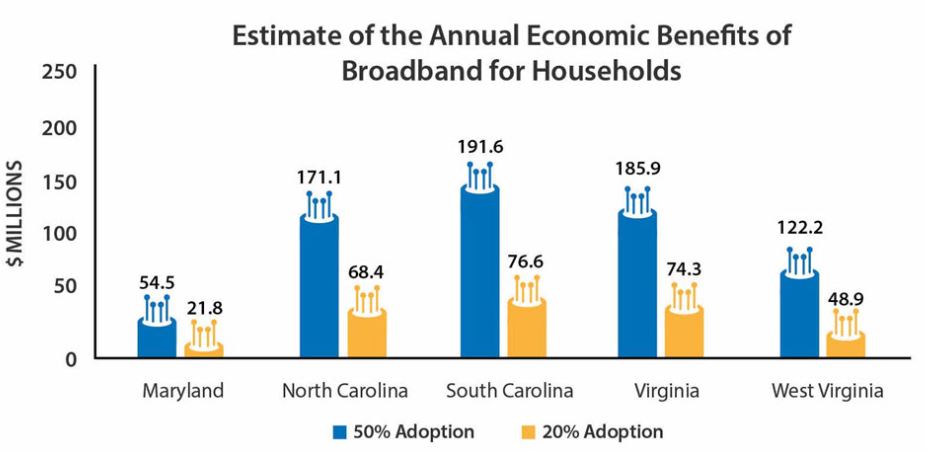

Reputable estimates of the cost of making high-capacity Internet service universal across the United States run in the $80-billion to $85-billion range, but the society-wide benefits may be worth the outlay, argues Alexander Marré, a Baltimore-based regional economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond in a recent paper.

There are multiple benefits, Marré contends. Broadband has positive effects for business-location decisions and employment growth in rural areas, research data shows (although effects can be stronger in rural areas that are closer to metropolitan areas than more remote regions). Broadband also enables rural consumers to choose from a wider array of goods and services, potentially saving more than $1,000 per household. High-speed Internet also can improve the efficiency of rural labor markets. It can improve access to healthcare via telemedicine and distance learning. And, as a desirable amenity, it can boosts home values.

The low density of businesses and households makes deployment of broadband infrastructure costlier than in metropolitan areas, and for-profit telecom companies can’t justify the low return on investment. But if the social benefits are as extensive as Marré contends, rural communities have a different cost-benefit calculus. His article explores several alternatives for bringing broadband to rural communities, including a Shenandoah Telecommunications (Shentel) projectin Virginia.

In his article, “Bringing Broadband to Rural America,” published in the Richmond Fed’s Community Scope December 2020 edition, Marré writes:

[Shentel] is beginning to offer fixed wireless service called “Beam Internet.”46,47 Shentel invested $17 million in spectrum licenses in Virginia, West Virginia, and Ohio and is providing 25 Mbps download speed service. The technology can support speeds up to 100 Mbps, which bodes well for the future as speed demands rise. The technology can be deployed in a matter of months rather than the years it takes to lay fiber. Each tower can serve customers within a five-mile radius if there are no significant obstacles in the way.

Another approach is letting electrical cooperatives the legal authority to extend broadband from the fiber-optic backbone installed along its electric distribution lines. The cooperatives’ easements and utility poles can significantly reduce the cost. Nationally, electric cooperatives could shave between $8 billion and $15 billion from the $80 billion tab of extending fiber to every unserved home. In the Fifth Federal Reserve district, the Choptank Electric Cooperative on Maryland’s Eastern Shore lobbied the Maryland legislature to let the cooperative provide broadband to 54,000 customers within its nine-county service area.

Marré also points to Public Private Partnerships, which can combine public and private funds, as a tool for financing rural broadband. In West Virginia, for instance, the Appalachian Regional Commission granted $2.35 million in seed money to a partnership that includes Marshall University, Marshall Health, and Mountain Health Network.

“It can be costly to get broadband to rural areas, but the potential payoff is high,” Marré writes. “Comparing the costs of expansion against the subsidies available today shows that more subsidies are needed to close the gap. Engaging electrical cooperatives, using alternative technologies, and, in some instances, public-private partnerships work best for getting the job done.”

Bacon’s bottom line: As a rule, I oppose government economic subsidies on the grounds that they misallocate resources from high-return investments to lower-return investments. Rural broadband, like rural electrification, might be an exception to the rule — especially if local communities have skin in the game.

It’s one thing to take federal and state government handouts. Free money? Sure, why not? It can’t hurt. Sorry, that kind of logic is not good enough. If communities believe strongly enough in the value of broadband, they should tap their own resources — electric co-ops, phone companies, municipalities, community foundations, universities, hospitals, and other major players — to make it happen.

One strategy that I never see mentioned is is rural densification. Rural settlement patterns in Virginia, as with the most of the U.S., is extremely dispersed. That requires more infrastructure per customer, which drives up-front capital costs. It would be interesting to compare broadband deployment in Europe where rural inhabitants cluster in villages, which in theory should drive down the cost per customer.

Perhaps rural Americas should embrace village-like settlement patterns. Twelve years ago Bacon’s Rebellion highlighted the thinking of Claude Lewenz, an American-turned-New Zealander, who had written a manual on “How to Build a Village.” His vision offered several distinct advantages, among them a sharp reduction of infrastructure costs — roads, utilities, broadband — per household. I still think it’s a brilliant idea. Such a community might need zero subsidies to support state-of-the-art Internet connectivity.

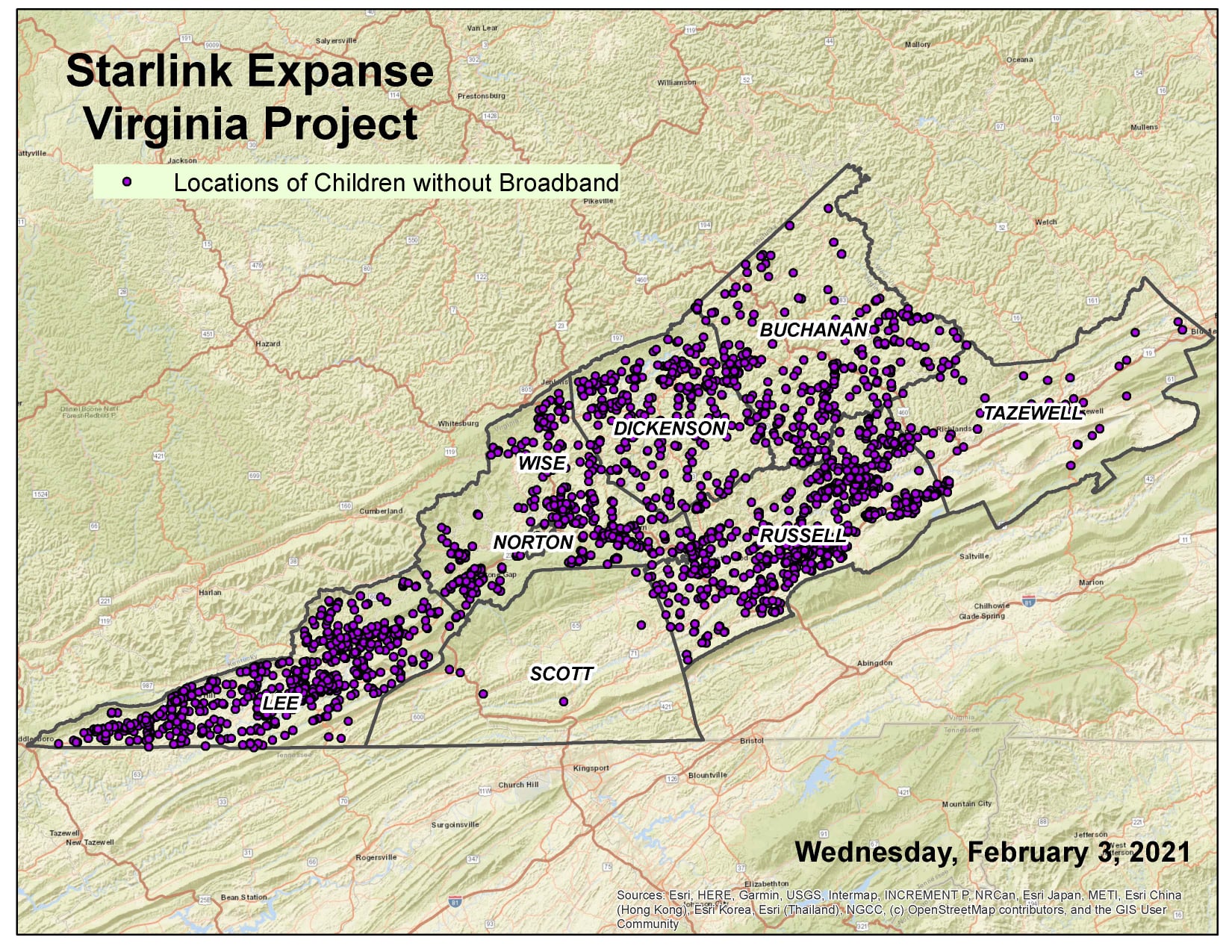

Update: One big hole in the paper was any discussion of low-earth-orbit satellite broadband. Elon Musk’s StarLink could be such a game changer that it could render earth-based alternatives irrelevant. On Facebook Jack Kennedy posts the map shown above. “Space-based broadband can eliminate this need in this calendar year,” he writes. “Want not for expensive fiber expansion with a Starlink connection.”

Update: One big hole in the paper was any discussion of low-earth-orbit satellite broadband. Elon Musk’s StarLink could be such a game changer that it could render earth-based alternatives irrelevant. On Facebook Jack Kennedy posts the map shown above. “Space-based broadband can eliminate this need in this calendar year,” he writes. “Want not for expensive fiber expansion with a Starlink connection.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.