by James A. Bacon

Yesterday my son and I visited the Man Ray exhibit at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Man Ray was the Annie Liebowitz of his day, photographing the celebrated poets, painters, novelists, singers, dancers, and composers of Paris in the 1920s, a time in which the City of Light was the world’s undisputed center of artistic ferment. The exhibit displays Man Ray’s black-and-white portraits ranging from American writers Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway to European painters such as Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dali. The exhibit portrays Man Ray himself as a creative genius who experimented with new photographic techniques and used cinema to explore the interplay between movement and light.

All in all, the exhibit was informative and well done. It illuminated a period of history for which I had little appreciation, providing context for America’s famous “Lost Generation” of expatriate artists, as well as dozens of Frenchmen, Spaniards, Englishmen, Latin Americans, and even Romanians of great renown and modern-day obscurity. (Who knew there were so many celebrated Romanian artists in the 1920s, certainement pas moi.) The exhibit also highlighted the role of women in the intellectual movements of the day. Paris in the 1920s was a crucible for women’s emancipation.

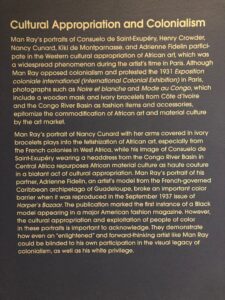

But there was one spoiler — a cringingly awkward placard about cultural appropriation. Man Ray, you see, had committed the cardinal sin of appreciating African art and incorporating it into some of his photographs. That, lecture the exhibit’s curators, amounted to “a blatant act of cultural appropriation,” which showed how “even an ‘enlightened’ and forward-thinking artist like Man Ray could be blinded to his own participation in the visual legacy of colonialism, as well as his white privilege.”

Are these people serious?

France was indeed a colonial power, but the French were not racially segregated as most of the United States was at that time. Paris was the center of a vibrant community of Blacks of American and Caribbean origin who were widely celebrated for their jazz, song and dance. The American-born Josephine Baker is the best known, but there were many others. Man Ray photographed many of them.

The exhibit credits Man Ray for opposing colonialism, protesting the 1932 International Colonial Exhibition, and breaking the U.S. color barrier by placing a photograph of a Black woman in Harper’s Bazaar — the first time a Black model appeared in a major American fashion magazine. He also gave visibility to African artistic traditions by placing masks and headdresses prominently in some of his compositions.

Regardless, states the exhibit, “the cultural appropriation and exploitation of people of color in these portraits is important to acknowledge.”

The placard reflects far more poorly on the intellectual poverty of our own time than it does on Man Ray or 1920s France. Contemporary Americans, it seems, are far more fixated on race as a defining personal characteristic than the avant garde artists in Paris a century ago.

The concept of “cultural appropriation” is absurd. The history of humanity is the history of the dissemination of technological, institutional, philosophical and artistic innovations. Civilizations and societies have borrowed from one another since the dawn of time, adapting and reshaping other cultures’ innovations to their own purposes. Societies that have been open to other cultures’ innovations have prospered; those that have closed themselves off stagnate or decay. For non-European examples in the 19th century, compare Meiji-era Japan, which embraced Western technologies and ideas, with imperial China, which walled itself off.

As Frans Johansson, the bi-racial author of “The Medici Effect,” has written, innovation occurs at the intersection — the intersection of technologies, of disciplines, and of cultures. Innovative societies borrow elements of other cultures, combine them, and reshuffle them with elements of their own. To accuse Man Ray of cultural appropriation for featuring African masks in his photographs is as obtuse and wrong-headed as criticizing African-American musicians of culturally appropriating European-invented trumpets, trombones, clarinets and pianos into their jazz compositions. Without cultural borrowing, jazz never would have been invented!

Apologizing for borrowing from other cultures is crimped, narrow-minded, retrograde, and harmful. It is a recipe for stasis and stagnation. It is divisive. It feeds grievance and resentment. It drives wedges between the races. And what possible good does it accomplish? Does the decrying of cultural appropriation make anyone, anywhere, better off? No, it doesn’t.

The United States is comprised of peoples from across the globe. We are the world’s greatest mixing bowl of cultures. The innovation that results from all the cross-borrowing is a major source of vitality. What a sad commentary it is that so many in our intellectual class are so obsessed with signaling their virtue on matters of race that they fail to appreciate this fundamental truth. Shame on the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for injecting such contemptible thinking into an otherwise marvelous exhibit. Shame!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.