by James A. Bacon

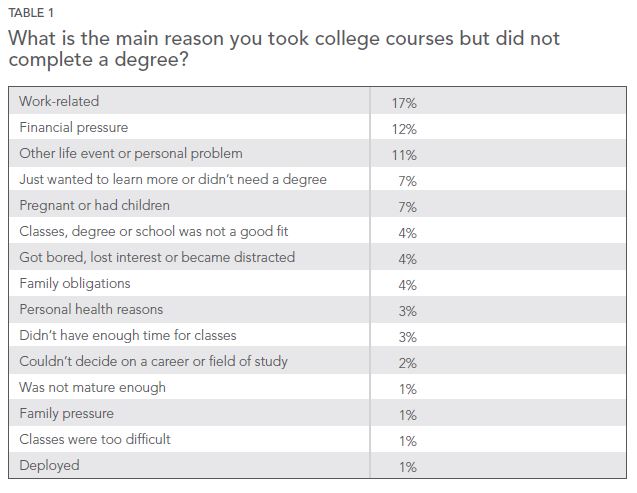

The biggest reasons students take college courses but fail to complete a degree are work-related, according to a Strada Education Network survey of more than 42,00 adults nationally with some college but no degree. Seventeen percent cited “work-related” reasons for ceasing their studies. The second mostly commonly cited reason was financial pressure, followed closely by life events/personal problems.

When people rack up thousands of dollars in student loans without obtaining an educational credential that will enable them to qualify for a better job, it is both a personal setback and a waste of social resources. The Strada study is important because it helps identify the reasons why many students fail to get degrees, and it provides lawmakers and colleges guidance in how to address the college dropout issue.

Governor Ralph Northam has budgeted $145 million to make community college tuition-free for low- and middle-income students pursuing jobs in high-demand fields. He cited numbers from Reynolds Community College showing that full-time students who dropped out before completing their degrees “usually had earned a 3.1 grade point average when they left school.” If they didn’t leave for academic reasons, the Governor surmised, they must have left for a lack of money.

After checking the Reynolds data, I found that conclusion was unwarranted. Although the data ruled out low GPAs as a reason for at least 40% to those who did not return for a second year of study, it did not address what their motivations were. I suggested that one other reason might be because they had found a job. There could have been other reasons.

However, the Strada data provides some evidence in support of Northam’s position.

When asked the main reason why they did not finish a degree, 12% of survey respondents cited “financial pressure.” When asked why they were not currently taking college courses, 12% said, “too expensive.” So, it’s fair to say that the financial barrier is a factor for one in eight college dropouts. When asked what would impact the likelihood of them re-enrolling, 52% of all respondents said free community college tuition would make a “great deal” of difference. So, it’s also fair to say that providing more financial support would encourage some to finish their studies.

But the Strada survey makes equally clear that there are many other obstacles, the biggest of which is work/life balance. Says the report: “Difficulty balancing school and work is a key reason people stop out of college. Educational providers need to acknowledge that a high percentage of their students will be working and going to school — and provide the flexibility to make it possible for these students to do both.”

Forty-seven percent of those surveyed said that courses and training that fit their schedule would make “a great deal” of difference in their decision to re-enroll. Another 47% said having guaranteed employment upon earning their degree would make a great deal of difference. Other important factors were “low-cost tuition” (as opposed to free tuition), courses and training that employers needed, and locally accessible learning centers. Les important factors were availability of distance learning and support for child care.

As Strada interprets the data, education must (1) be affordable, (2) fit education into the work/life balance, and (3) provide students “a clear career benefit to invest the time and money in further education.”

Now, let’s circle back to Northam’s $145 million plan. Low-income students already qualify for federal Pall grants, federal loans, and state financial aid. But, as the Governor says, “life gets in the way.” Student loans don’t cover the cost of child care or cars with busted radiators. His plan, which would include cash grants of up to $1,000 per semester and $500 per summer term, would help low-income students with no spouses or family members to fall back on. Will the sum be enough to get them over the hump? That’s unknown.

The Strada survey suggests that Northam’s G3 program will do nothing for the seven-eighths of students who did not cite financial issues. However, if it promotes upward income mobility for students from low-income households, it may prove worthwhile. If low-income students get better jobs, pay more in taxes, and consume less in government benefits, the state may even get a return on its investment. Undoubtedly, it’s preferable to spend public funds on education that helps people escape poverty than to spend money supporting them in proverty.

Whether G3 makes a measurable difference in the number of lower-income Virginians getting degrees, we’ll have to wait to find out. Let’s hope someone is measuring the impact of the program to see if it does what it’s intended to do.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.