by James A. Bacon

In an essay posted earlier this week on the StatChat blog, Spencer Shanholtz with the Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia explored the relationship between housing values and school quality. He documents the reality that children living in census tracts with low-value housing are more likely to attend low-performing schools. He finds this disturbing. “Children in lower-cost housing should be able to attend good schools,” he says.

I quite agree. Every child should be able to attend a good school. The pertinent question is whether it is necessary for a school to be located in an affluent neighborhood and have students from affluent families in order to accomplish that goal.

In this, first of two blog posts, Shanholz provides some useful data. It would unfair to critique his argument until he publishes the second post. For now, let’s take a look at the case he makes and raise some questions for him to answer in his follow-up post.

The first challenge is to measure school quality. Shanholz uses a school proficiency index developed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development designed to “help communities analyze challenges to fair housing choice” and “address the fair housing barriers in their community.” Percentile-ranked values range from 1 to 100. Higher scores indicate higher qualities schools.

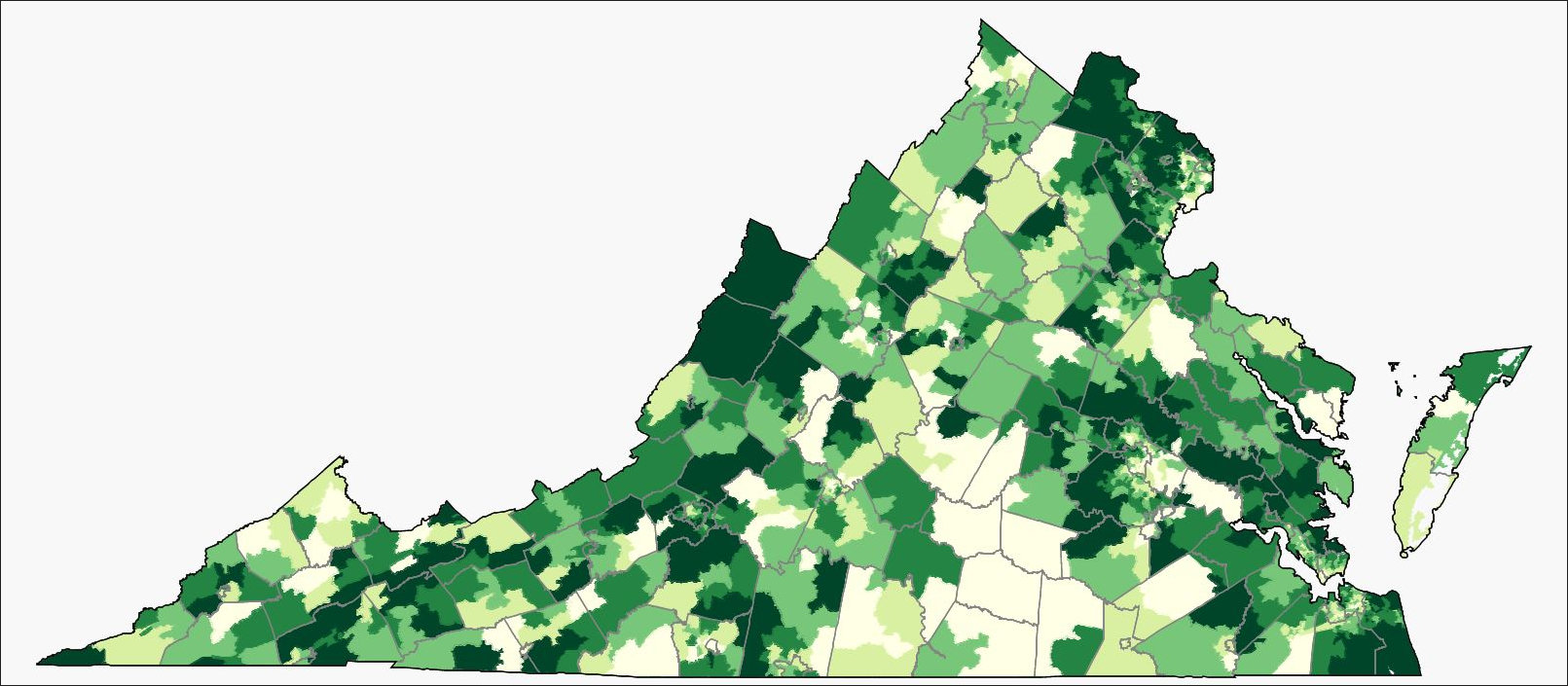

School proficiency levels vary widely across Virginia, Shanholz writes.

High-performing schools tend to be clustered in the suburbs around the state’s major metro areas and in certain rural neighborhoods. Regionally we see the highest average school proficiency index in the Hampton Roads region at 59, followed by Northern Virginia at 53. The West Central and Valley regions are also above the state average of 45. Southside has the lowest mean school proficiency score by far at 21.

Some rural areas buck the larger trend. Rural Bath County scores highest in the state with a school proficiency index of 92, followed by exurban New Kent County at 91, and urban Falls Church at 91. Then come suburban Loudoun, rural Highland, and Covington, a small city in a rural setting, at 82.

Despite the exceptions, Shanholz notes that average school proficiency index increases with median housing values.

Shanholz argues that the high price of housing in census tracts with the best schools essentially price poor households out of neighborhoods with good schools — a defensible proposition. He then concludes, “The anecdotal relationships presented here demonstrate the difficulty of obtaining low-cost housing in an area where a family can send their children to a quality school.”

Bacon’s bottom line: Big question: Are the high-performing schools high-performing because they have better teachers, newer buildings, and more resources — advantages that can be transferred to students from poor families? Or are they high performing because the students attending the schools come primarily from families with educated parents of financial means who pass on their learning to their progeny — advantages that cannot be transferred to students from poor families?

The exceptional performance of places like Bath County, Highland County, and the City of Covington are proof positive that, while more resources might be helpful for creating a high-performing school, they are not essential. Conversely, there are school systems with ample financial resources (the city of Richmond comes to mind) where poor students perform abysmally.

A final observation: Shanholz presents no evidence here that transferring a poor kid to a great school in a wealthy neighborhood will improve that kid’s academic performance. But let’s wait and see what he has to say in Part 2 of his essay. Perhaps he will address these points.