by James A. Bacon

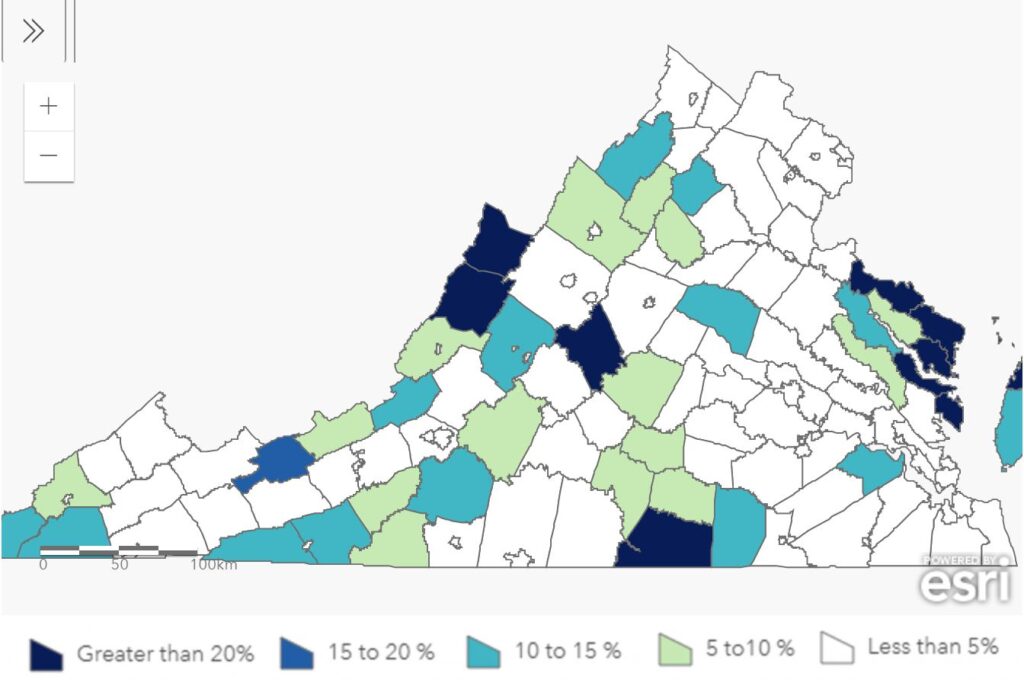

Virginia has more than 88,000 vacation homes, about 2.5% of all homes in the Commonwealth, according to the University of Virginia’s Demographics Research Group. These “seasonally vacant homes” intended mainly for recreational use are overwhelmingly located in amenity-rich rural locales along the Chesapeake Bay, the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains, or man-made lakes.

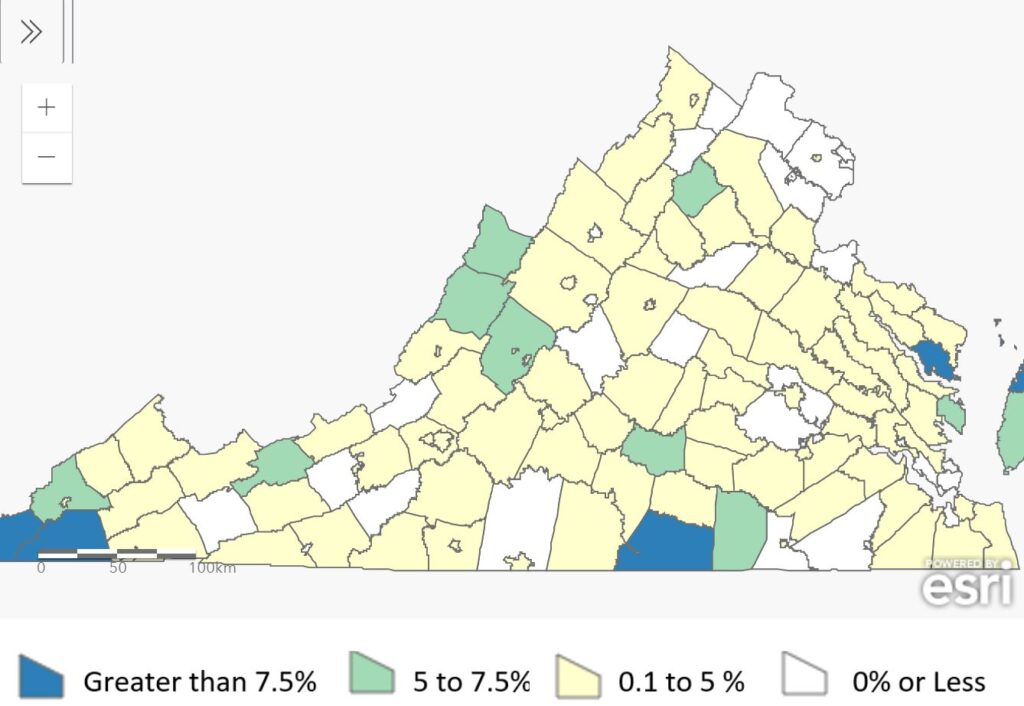

Moreover, reports StatChat, the vacation share of housing has increased since 2018 in most jurisdictions — more than 7.5 percent in some cases.

Bacon’s Rebellion has argued that Virginia’s rural counties should position themselves as destinations for retirement and vacation housing as an economic development strategy. Retirement and rental properties boost the tax base and create service jobs in localities where employment opportunities are otherwise scarce.

The StatChat numbers demonstrate how several localities have done so successfully already. I was unaware that these metrics even existed. It would be revealing to compare Virginia to neighboring states of Maryland, North Carolina, West Virginia and Tennessee to see the extent to which our rural communities are living up to their potential.

The StatChat article does suggest a potential downside to the retirement/vacation housing trend — rising real estate prices. In effect, some counties could see a rural version of urban gentrification in which affluent out-of-towners bid up the price of real estate and displace locals.

“Wealthy residents and retirees living in Northern Virginia, Richmond, Hampton Roads, and even Raleigh who increasingly desire a weekend or seasonal home may be attracted to the affordability and solitude of rural Virginia,” writes author Spencer Shanholtz. “As a result, demand and prices can be expected to continue to rise, creating affordability problems.”

However, the problem seems far less acute than in urban areas which combine fast-growing populations with strict land-use controls that limit the supply of new housing.

Shanholtz summarizes his findings as follows:

The high and rising share of vacation homes in areas of Virginia that are experiencing outmigration, aging, and low incomes may provide an economic boost, but it is important to take into account the unintended consequences of rising home prices. As destination areas become more popular, consumption, expenditure, and local tax revenue may get a boost. This creates more jobs, yet it may cause housing prices to escalate, making it difficult for local workers to find a place to live. Will vacation housing drive economic development in Virginia? Will additional vacation units raise affordability issues in those localities? Local government officials will need to address these questions moving forward.

From my vantage point, the upside looks a lot bigger than the downside for rural jurisdictions. Local government officials should be taking stock of their amenities — waterfront footage, mountain vistas, natural wonders (the Natural Bridge, Brinks Interstate Park), hiking and biking paths, cultural and historic assets (the Country Music trail), and charming small-town downtowns — and building on those.