David Shephard, publisher of The Virginia Gentleman blog, has followed politics in the Old Dominion for many years, and he has long admired the Garrett Epps novel, The Shad Treatment, a fictional rendering of the 1973 gubernatorial contest between Mills Godwin and Henry Howell. Shephard’s recently published book, Elections Have Consequences, is his effort to follow in the Epps tradition.

Set circa 2021, the election Shephard recounts is a contest between Democrat Ronnie Norton and Republican Angela Parrish. It’s not a spoiler to tell the reader that Norton wins, for Shephard devotes the second half of his tale to what follows: the newly-elected governor is engulfed in scandal — a yearbook photo surfaces of Norton in blackface standing next to someone in Nazi regalia. To survive politically, he capitulates to the militant left wing of the Democratic Party and presides over a wave of social-justice legislation.

In his preface, Shephard swears that Ronnie Norton (initials R.N.) is purely a figment of his fertile imagination, thus waving off any comparisons with Ralph Northam (initials R.N.). He makes the same claim of his dean of the capitol press corps, Steve Cohen, who bears passing similarities to the Richmond Times-Dispatch’s Jeff Schapiro. Presumably, we are to view as no more than coincidental resemblance his introduction of Republican campaign consultant Mark S. Boyd, whose name bears a remarkable resemblance to Republican campaign consultant Boyd Marcus.

But the deliberate similarities — mixed with innumerable references to real governors such as Jerry Baliles and George Allen; to real Virginia cities, towns and places; to real Virginia higher-ed institutions from Hollins and Mary Baldwin to the University of Virginia; and to uniquely Virginia effluvia from the Ask the Governor radio show to the burial of Stonewall Jackson — are all part of the fun.

Elections Have Consequences is not a great work of literature. The language and characters are pedestrian, and the plot is not especially compelling. But if you enjoy following Virginia politics — especially if you follow Virginia politics from a conservative perspective — you will find the book an entertaining read. Shephard has a deep knowledge of Virginia history, places and culture, a keen sense of how politics works in Virginia, and a sharp eye for politicians’ weaknesses and hypocrisies. Especially politicians on the left.

How can a conservative not read and fail to appreciate these words put into the mouth of the novel’s insufferable Episcopal-priest-turned-militant-leftist Ann Lee Brand: “It isn’t right versus wrong, it’s good versus evil. Conservatives are evil; they are against progress and equality. They must be destroyed, not just defeated. That is, defeated and silenced. They can live, but they must pay a price for spreading their views.”

Then there’s this description of Norton’s wife: “Paula longed to be a social justice warrior. She felt bad because she had never really had a Hispanic friend, an African American friend, a Jewish friend, a Muslim friend, a gay friend, or a transgendered friend. While she was good at all the virtue signaling, deep down she felt that she was just a phony, wealthy white Mclean liberal.”

In Elections Have Consequences, conservatives are the good guys and liberals and progressives are the bad guys — a counterpoint to 99% of the novels, movies and television shows produced in America today. Shephard is no more fair when he portrays his lefty characters either as zealots or craven opportunists than most popular media are in depicting conservatives as bigots and ignoramuses.

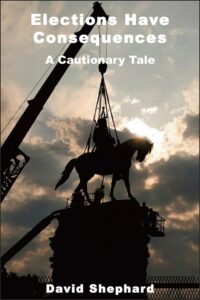

While his characters may lack nuance, Shephard excels in capturing the tenor of the times, consumed as it is by debates over race and gender. The politicians in Elections Have Consequences grapple with renaming schools, combating microaggressions, banning racist and sexist speech, admitting transsexuals into beauty pageants, raising the threshold for shoplifting charges, and, presciently, appointing candidates to the Virginia Commission on Fine Art and Historical Sites. It becomes a minor plot point when three members of the commission are “stuck to the view that the so-called Confederate monuments had ‘historic, cultural and artistic value.’”

Shephard’s Governor Norton has more misgivings about wokeism than Ralph Northam ever evinced publicly, and his chief operative is more open to opponents’ talking points than anyone I’ve ever observed on the left, but conservative readers will love the exchange between the two men that demolishes the confederate-statues-as-emblems-of-white-supremacy narrative.

In Shephard’s telling through the eyes of the operative Steve Beaman, generations of Southern men who had fought in the Civil War were dying off. Their children, mainly their daughters, raised money to put up statues before they died. The Lee statue in Richmond was such a hit that more monuments were built along Monument Avenue. Confederate veterans held reunions in the city, parading around with gray hair and gray coats. The statues were all about honoring the veterans and their sacrifices, not about race, not about Jim Crow, not about White supremacy.

“But that was then,” Beaman concludes. ‘It’s a new day in Virginia.” The statues had to come down.

Shephard’s book, though a flight of fancy, becomes more prophetic with each passing day.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.