by James A. Bacon

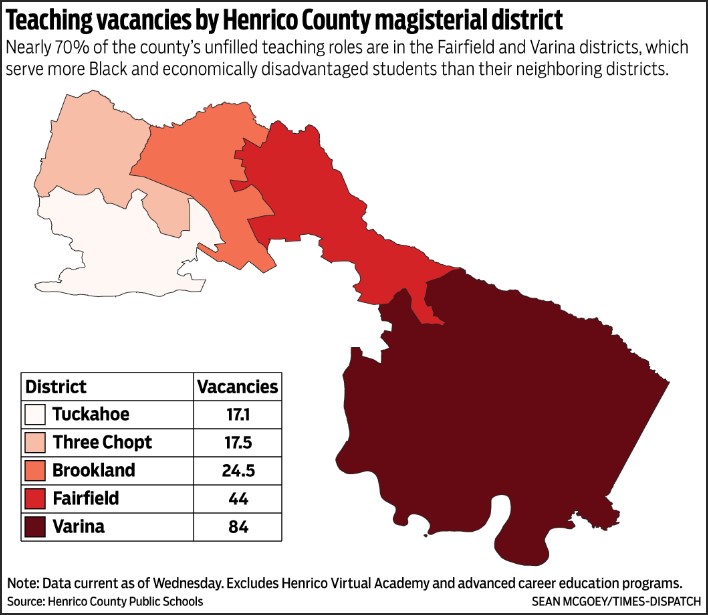

I have long contended that the teacher shortage is most acute in Virginia’s high-poverty schools where student discipline is the worst, but I didn’t have the school-by-school data to back up the proposition. Now the Richmond Times-Dispatch has published data for Henrico County comparing vacancies in the school system’s five districts. And it turns out that the affluent districts in the county’s west end have the fewest vacancies while the high-poverty schools in the east end have five times as many.

Days before the new school year begins, Henrico County has nearly 190 teacher vacancies. Nearly 70% are in the Fairfield and Varina districts.

“The three schools with the highest number of vacancies — Varina High, Rolfe Middle and Achievable Dream Academy at Highland Springs — are all in the Varina District,” notes the RTD. “More than 70% of the students at each school are Black, and at least 60% are economically disadvantaged, as defined by the state.”

I don’t think this data comes as a surprise to anyone. Where the story gets interesting is how the RTD seeks to explain it.

“Young, perky teachers who begin their careers at hard-to-staff schools can burn out quickly,” notes the RTD.

And why do they burn out? The root cause, we glean from the various sources quoted, is “trauma.”

The RTD quotes Emily Williams-Fitz, who started her career in a Title I school in the Varina district and then transferred to a school in the west end.

“You’re working with more kids who may have experienced trauma and are just not getting their basic needs met at home,” Williams-Fritz said. “What that [means] for teachers is that it takes more patience and understanding and active communication with families to bridge this gap and make sure that their students are successful. It also means that you’re having to fill these basic needs that are missing at home.”

What drove her out was the lack of support from HCPS’ central office. “The people who made decisions about my job were so out of touch with what it was like to be inside of a classroom every day,” she said.

Alicia Atkins, a school board member who represents the Varina District, said it is harder to recruit in areas with (in the RTD’s words) “more need and more trauma.”

And then the RTD quotes Megan Hyatt, who also worked at a Title I school before moving to a western Henrico school, “The types of behavior you’re seeing might be more associated with trauma, and those are much deeper behaviors than a kid who just doesn’t want to do their homework.”

See how the syllogism works? Teachers are burned out by the “behavior” of students at school. Tracing the behavior back to its roots, students misbehave because they have experienced “trauma” outside school.

The concept of “trauma” plays a big role in the “social-emotional learning” paradigm that now governs Virginia schools. “Trauma” appears to be a highly elastic term. It encompasses phenomena that one would genuinely consider to be traumatic: from child abuse and sexual exploitation to homelessness and witnessing shootings, but it extends to forms of adversity as amorphous as bullying, economic insecurity and the all-purpose explanation for every social ill, systemic racism.

Based on the proposition that misbehaving kids are suffering from trauma, social-emotional learning seeks to teach children self-regulation, how to resolve disputes without violence, and how to communicate socially and emotionally — learning at school what they failed to learn at home. As The Committee for Children puts it, “A trauma-informed learning environment helps students feel safe and supported — socially, emotionally, and academically — and these supports extend to students’ relationships, self-regulation, and well-being.”

It sounds good in theory. In practice, creating a “trauma-informed learning environment” means tolerating a lot of behavior that would have earned swift chastisement in the past. Children learn that rudeness, defiance and disorderly behavior go unpunished. Teachers don’t just feel disrespected, frustrated and overworked; many, especially women, feel physically vulnerable. Increasingly, teachers find themselves involved in physical altercations.

Somehow, such harsh realities did not make it into the RTD account. (An interesting question is whether the teachers the RTD interviewed are so brainwashed that they could not bring themselves to mention the continual defiance, disruptions and risk of violence, or whether the RTD reporter simply omitted mention of anything that might mar the social-justice narrative.)

I fear that the problems may not be fixable. The culture of many high-poverty schools is so far gone, and school officials (and probably many teachers, too) are so deeply in denial and so unwilling to speak in anything but euphemisms, and politicians are so quick to tar critics of the system as “racist,” that I can’t imagine any way to turn the situation around.

What ails Virginia’s high-poverty schools is not something that more money, more teachers and more school psychologists can solve. The only solution may be launching charter schools and voucher-funded private schools that can start fresh, set new, higher expectations of students and parents, and enforce higher standards of behavior.