by James C. Sherlock

by James C. Sherlock

The goals, good ones, of Virginia’s Pre-trial Services Agencies (PSA) is

- to advise courts on pre-trial release risks;

- to supervise the population on pre-trial release to reduce recidivist crime and failures to appear (FTAs) and

- through both efforts to help assure public safety.

By the government’s own evidence, those goals have not been realized.

A major Virginia Crime Commission study reported the PSA program made no difference at all compared to courts and pre-release populations not served by PSA. It’s overall success rate was no higher than 62%. The other 38% represent a danger to the citizens of Virginia.

This article is written for two reasons: (1) to get the Youngkin administration as an urgent public safety issue to improve the PSA system or try something else; and (2) to expose that the DCJS annual reports to the governor and General Assembly have been at best wrong.

The evidence of PSA ineffectiveness submitted by the Virginia Crime Commission is scientifically derived by external review. The reports of DCJS are derived from internal data to support budget requests.

The very large gaps in assessment of PSA effectiveness between the two are impossible to rationalize.

In order to make those two separate cases, I will introduce evidence of both issues.

In 1995, Pretrial Services Agencies (PSA) were authorized (mandated for those seeking approval of jail projects) in Virginia by statute with the passage of the Pretrial Services Act, § 19.2-152.2.

It is the purpose of this article to provide more effective protection of society by establishing pretrial services agencies that will assist judicial officers in discharging their duties.

From an organization called the Virginia Community Criminal Justice Association, an advocate “for the growth of programs that decrease incarceration rates by effectively utilizing community resources”, we have this:

Pretrial services agencies provide information and investigative services to judicial officers (judges and magistrates) to help them decide whether persons charged with certain offenses and awaiting trial need to be held in jail or can be released to their communities subject to pretrial supervision.

Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project Preliminary Findings , the only major study of the effectiveness of PSA services, found they added no value compared to jurisdictions without them, leaving the criminal justice system with a false sense of security in release decisions. Indeed, PSAs put the public at risk by influencing the courts to release on bail persons with combined recidivism and failure to appear rates shown to be a minimum of 38% and that may approach 50%.

The 2020 General Assembly and governor, with that report in hand, expanded PSA services to 15 additional cities and counties.

In 2021, the General Assembly passed and the governor signed legislation to remove from Virginia law the presumption against bail by judges and magistrates. Readers can see the changes at the link.

The intended result of that legislation: more charged criminals on the street, supervised by PSAs.

Virginia Pretrial Performance Outcome Measures were defined in 2014.

- Pretrial Court Appearance Rate – The percentage of defendants on pretrial supervision who attend all pretrial court appearances. Sub-Measure 1.1 – The percentage of case closures where the closure type is “failure to appear.” Sub-Measure 1.2 – The percentage of scheduled court appearances attended.

- Public Safety Rate – The percentage of supervised defendants who are not charged with a new offense while under pretrial supervision.

In order to be considered a “new offense,” the following criteria must be met: (a) the offense date occurred during the defendant’s period of pretrial supervision; (b) the defendant must be taken into custody by authority of law or to be issued a ticket, summons, or warrant for a violation of criminal municipal, state or federal misdemeanor or felony crime (those coded within statute as criminal offenses).

Arrests for probation or parole violations are excluded from the public safety rate.

3. Success Rate – The percentage of defendants under pretrial supervision who (1) are not revoked for technical violations of the conditions of their release, and (2) appear for all scheduled court appearances, and (3) are not charged with a new offense during pretrial supervision.

Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project Preliminary Findings

The findings raise serious questions about the effectiveness of:

- the Pretrial Services Agencies pre-trial supervision of charged criminals released on bail; and

- the Virginia Pretrial Risk Assessment Instrument (VPRAI), which is the tool used by PSAs to assist judicial officers in determining an overall combined risk of public safety (recidivism) and FTA (Failure to Appear).

Limitations to data

The outcome measures for public safety rate were incomplete, and understated the true numbers of crimes.

Out-of-state crimes not counted. In footnote 2:

out-of-state criminal histories were not included in the dataset of this Project

The authors also footnote that the out-of-state crime data was proscribed for use for this purpose. OK, that could not be helped, but it was a limitation.

Arrested for, not just committed a crime. Another limitation that also underestimated the recidivism rate but was in compliance with the Virginia definition was that the person out on bail had to have been “arrested for a crime … during the pre-trial period” rather than having “committed a crime during the pre-trial period”.

Together these seem significant limitations on the actual recidivism rate. They certainly resulted in understatement of the recidivism rates of the subjects of the study.

Findings

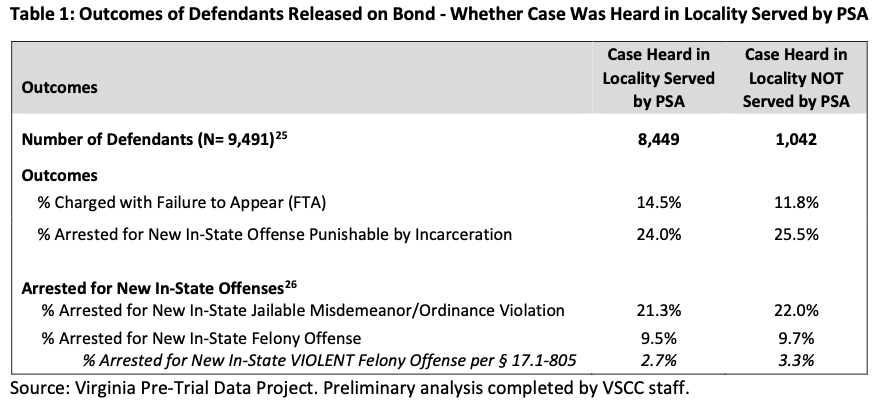

Finally, there are the hard numbers of outcomes of those released before trial:

The PSA program is run by the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS).

The report found what you see in the chart above:

Overall, there were no significant differences in terms of public safety or court appearance rates between defendants released on bond whose cases were heard in localities served by PSAs and localities that were not served by PSAs. Defendants whose cases were heard in either type of locality had similar demographics, risk levels, and outcomes based on the variables examined at a statewide level. [emphasis added]

Restated, the study found that PSA’s, funded by the state and local governments at nearly $20 million in FY 2020, added no value to either public safety or court appearance rates.

So, with that in hand, the Governor and the General Assembly in the 2020 Appropriations Act expanded the pretrial services to 15 additional cities and counties. Proving once again that government programs are the closest thing to eternal on earth.

Progressives controlling Virginia government, in the face of proven failure of one of their programs to provide any value, appropriated additional funding.

We hope that those re-arrested were not re-released. But in those jurisdictions controlled by members of the Virginia Progressive Prosecutors for Justice, citizens should not bet on it.

The Real Numbers

The Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project found that about 38% were recidivists or FTAs regardless of whether they were subject to PSA services or not.

That includes the 25% who were proven recidivists under the data limitations of this study, but none of those who

- committed a new crime in-state and were not arrested for it until after the pre-trial period; or

- committed a crime out of state during the pretrial period.

So let’s say, for discussion purposes, that instead of 38%, 45% of those studied for this report were pre-trial recidivists or FTAs. Seems a reasonable conclusion given the data limitations of the study.

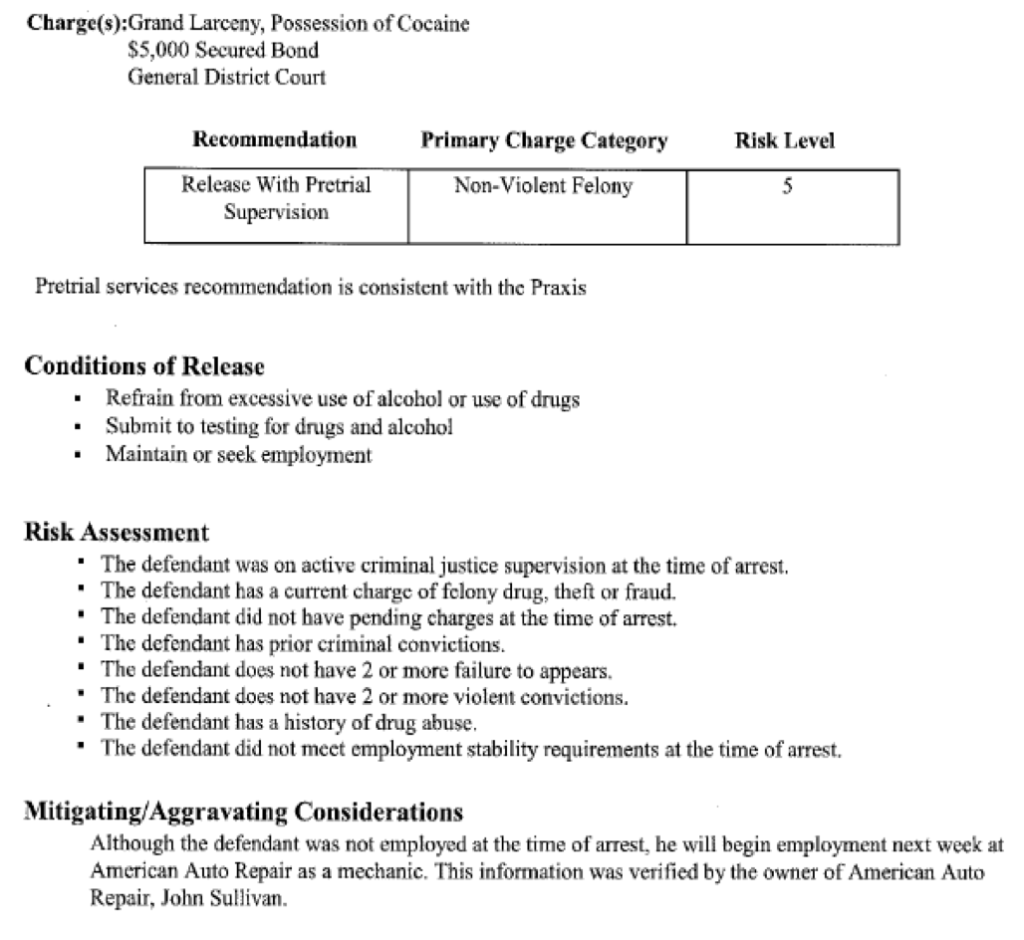

The assessment tool. The tool used by PSAs during the period of the study and today is VPRAI.

VPRAI Instruction Manual, Version 4.3, has not been updated since 2018. An example of the output of VPRAI is offered in the Manual.

Looks professional.

But Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project Preliminary Findings showed VPRAI was wrong as a predictive tool nearly half of the time.

Was that because of a failure of the tool or failure of the pretrial “services” provided by the PSAs?

We don’t know. We just know that those services were shown not to work any better than having no PSA at all. And that the system of pre-trial release as currently constituted leaves citizens in danger.

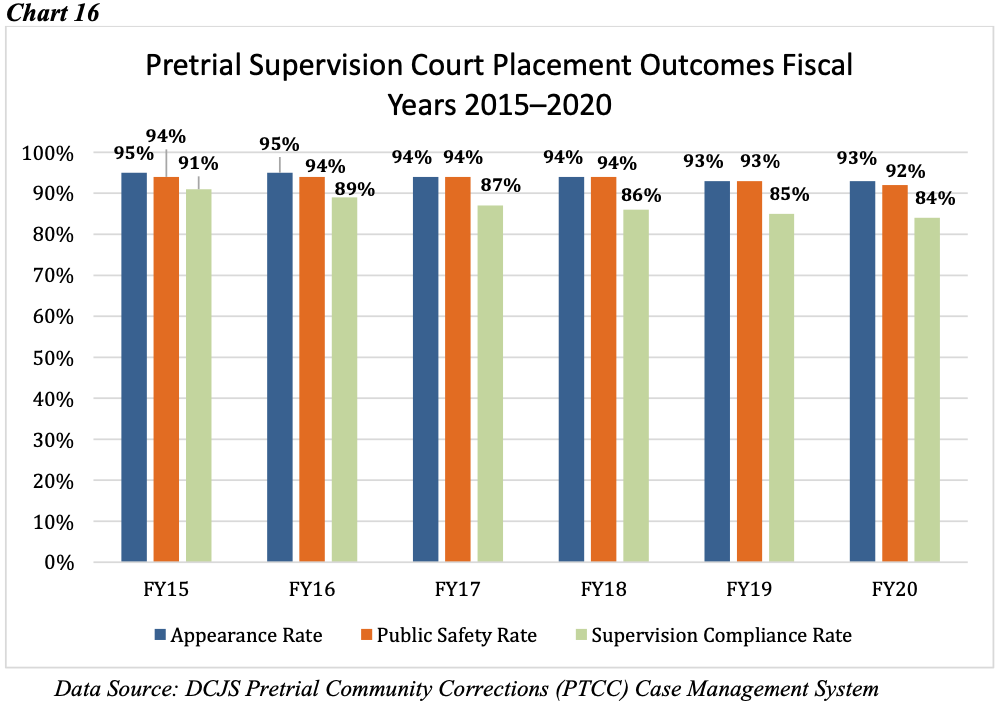

Data contradicting Virginia Pretrial Project Findings in annual DCJS budget requests

The required annual Report on Pretrial Services Agencies is submitted by DCJS to the Governor and General Assembly in January of each year in support of its budget.

It has painted a very rosy picture of PSA success.

The annual outcomes of appearance rates and public safety rates in the chart below are so high and so unnaturally stable over a six year period as to cause a second look.

It shows 6% failures to appear (FTA) and 6% recidivism in FY 18 for the PSA-supervised population.

Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project Preliminary Findings from the Virginia Crime Commission reported 14.5% FTA and 24% recidivism respectively in that same fiscal year for the same population.

The FY 18 data presented to the governor and General Assembly by DCJS in support of its budget uses the same chart every year updated for the next FY. The FY 18 numbers are irreconcilable with those in Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project Preliminary Findings, at least by me.

Someone will need to try to do that, and determine why they are different by magnitudes of between 2 and 4.

This is a government mess. The government needs to fix it.

General Assembly and Governor

In 2020 and 2021 Virginia General Assemblies and the governor had both reports before them when writing legislation and the budget. The DJCS- reported 88% PSA success rate (combining appearance and public safety rates each subtracted from 100) apparently carried the day.

Virginia Pre-Trial Data Project Preliminary Findings, with its reported 62% PSA success rate (which was, as demonstrated, worse than that), was unread or discounted.

The General Assembly and Governor Northam expanded the PSA program and changed Virginia law to provide a presumption of pretrial release. The intent of the law was to release more people charged with a crime pre-trial.

Into the PSA system.

Bottom line

What we know from Virginia Crime Commission study is that at minimum of 38% of criminals released based on an assessment that used VPRAI as a predictive tool either committed another crime pretrial or failed to appear.

Such tools are algorithms fed data. The algorithm is a set of rules to be followed in computers in pre-trial release risk assessment operations.

The VPRAI algorithm is designed to predict the success of the PSA system of supervision given a specific person to supervise in pre-trial release. Success is defined as that releasee not getting arrested for another crime pre-trial and showing up for trial.

It is fed risk assessment data as in the example recommending “Release with Pre-trial Supervision” above.

Yet a very high percentage of the accused released as a result of that VPRAI assessment system in fact committed another crime or failed to appear or both. That is what failure looks like.

With that known result, both the algorithm and data inputs of VPRAI must be examined. The contractor tasked to do that will likely do two things:

- First, reenter the original data and modify the algorithm until it provides predictions that eliminate the errors.

- Then, use the original algorithm and enter additional data until the tool provides predictions that eliminate the errors.

That is a professional way to isolate the causes of the errors. The causes may prove to be some combination of algorithm and data.

But supervision compliance is noted as a weakness even by the DCJS reports.

I suspect but do not know that the VPRAI algorithm as written may significantly overestimate the success of the PSA pre-trial supervision program. That could help explain how jurisdictions without PSAs had the same success with pre-trial releases as jurisdictions with them.

But whatever the cause, the PSA system has been proven to be dangerously ineffective.

Most citizens of Virginia, including me, favor well-considered, risk-based and carefully supervised pre-trial release. We don’t favor the failure of such a program.

Make it work or do something else.

The Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services was offered a period to comment on this article. The reply had not been received by press time.

Updated August 6 at 12:30