An abandoned gasoline station in North Carolina that failed after that state raised its fuel taxes substantially higher than Virginia’s.

By Steve Haner

Monday the organizers of the Transportation and Climate Initiative, a carbon tax and rationing regime for Virginia motor fuels, will be announcing details of the underlying interstate compact, according to media reports.

The media in Virginia has been disinterested in the issue, but the debate is raging in New England. The Boston Globe set the stage with a story last week. While 12 states and the District of Columbia have been involved in the planning, there remains some suspense over which states will press forward. New Hampshire is already out, and some other governors have expressed concerns.

During the 2020 General Assembly, skeptical Virginia legislators pressed Northam Administration officials on the issue and were assured that any proposed interstate compact would come to the General Assembly for approval.

How many details will be revealed Monday? Will we know the initial carbon tax amounts planned for 2022? How much Virginia revenue it is likely produce in that year and the following ones? How Governor Ralph Northam plans to spend it? Or will Virginia take a pass, at least in part because that same 2020 General Assembly already approved major fuel tax increases with elections looming?

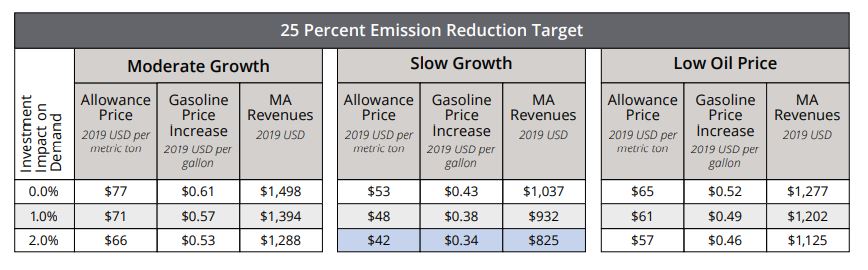

From Tufts University Center for State Policy Analysis, November 2020. This shows the projected 2032 TCI allowance prices, gasoline price increases and revenue in Massachusetts. The impact in Virginia should be similar.

The legislators and voters in Massachusetts have more background data to work with than we do, thanks to a report from the Center for State Policy Analysis at Tufts University. The report is supportive of the goals of TCI, referring to the “baleful emissions” from motor fuels, but also refreshingly honest about the economic implications.

The report should be read by every legislator, stakeholder, and reporter. It supports every concern highlighted in previous reports on Bacon’s Rebellion. The conclusions are consistent with a report sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy from another Massachusetts research group, the Beacon Hill Institute.

The researchers at Tufts have predicted major price increases for gasoline and diesel, in the range of 20 to 30 cents per gallon initially and then up to 40 to 50 cents per gallon in the out years. The report is quite candid that any oil wholesaler forced to buy carbon allowances will pass the cost to consumers.

“And far from being an unfortunate side-effect, this pass-through to consumers is part of why TCI is expected to reduce emissions. In the short term, higher gasoline prices will encourage people to seek ride-sharing options, consider public transit, and rethink the expense of shipping goods by truck.”

The carbon allowance is only part of the calculation behind rising prices. TCI freezes the supply of fuel at current levels and then begins to artificially reduce that supply. The goal is to shrink fuel sales 25% over ten years, and the supply and demand pressures drive up the price.

The Tufts summary also admits that the proposal had a more harmful impact on low-income consumers and on those more rural parts of the state where longer commutes are common. If you believe there will be health benefits (debatable) from slightly reduced emissions, they will be in the urban core. If you believe consumers can easily transfer to mass transit or even walking or biking, that will also be in the urban core.

Massachusetts with its 7 million people is substantially smaller than Virginia with 8.5 million and covers less land area. Tufts predicts a massive influx of tax revenue from the carbon tax for the Bay State, and it is fair to assume Virginia’s will be in proportion. Tufts is projecting up to $1 billion annually starting with 2022, growing from there. That is assuming the states agree on that 25% reduction goal. A tighter goal forces a higher carbon tax.

Tufts dismisses the likelihood that drivers in that state will simply go across state lines to fill up but notes that tactic will work in other parts of the region and be most attractive to interstate truckers.

“Some TCI states will inevitably border non-TCI states, which could create perverse incentives for drivers to hop the border and fill up in non-TCI jurisdictions. This problem will be exacerbated if TCI ends up attracting a patchwork of states, rather than a contiguous region.”

Virginia is in such a patchwork. Non-TCI states West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina will all beckon as lower cost sources for gasoline, diesel, and the other commerce that takes place at those stations. Trucking companies carefully plan their fuel stops.

The folks at Tufts recognized that if the program works, and gasoline sales do drop appreciably, so will the traditional transportation revenues.

“By encouraging people to drive less and switch to electric vehicles, TCI would reduce revenues from excise taxes. In a separate calculation, we find that these losses would offset roughly 4 to 5 percent of the revenue gains from TCI, though the interplay is complicated by the fact that excise taxes are generally used for different purposes.”

Four or five percent? If true, what that should tell you is that the TCI carbon taxes will ultimately be substantially more lucrative to the state than the gasoline and diesel taxes ever were. But it is also based on Massachusetts data, not Virginia. Will anyone even make such a calculation for Virginia before legislators vote?

Finally, the Tufts report agrees with the data from TCI’s own studies that CO2 emissions from transportation sources are already going down substantially without any forcing necessary.

“Without TCI, emissions from motor fuels are likely to fall between 2022 and 2032. Our central estimates suggest a decline of 14.2 percent (in our moderate-economic-growth scenario) or 17.5 percent (in our low-economic-growth scenario).”

The TCI data also reports a range of possibilities but centered on a 19% drop in emissions over ten years as likely. So, the vast majority of the CO2 reductions being sought will happen anyway, with no taxes, no rationing, and no legislative battles of how to spend the piles of money. The same is true about the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, by the way – it didn’t change the expected CO2 reductions from power plants one bit. It is just a tax increase.