Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), “Pandemic Impact on Public K-12 Education.” Click for more legible image.

by James A. Bacon

In what will come as no surprise to Bacon’s Rebellion readers (other than the reality-denying ankle biters frequenting our comments section), Virginia public school staff cite poor student behavior as their most serious challenge, found a study of the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC).

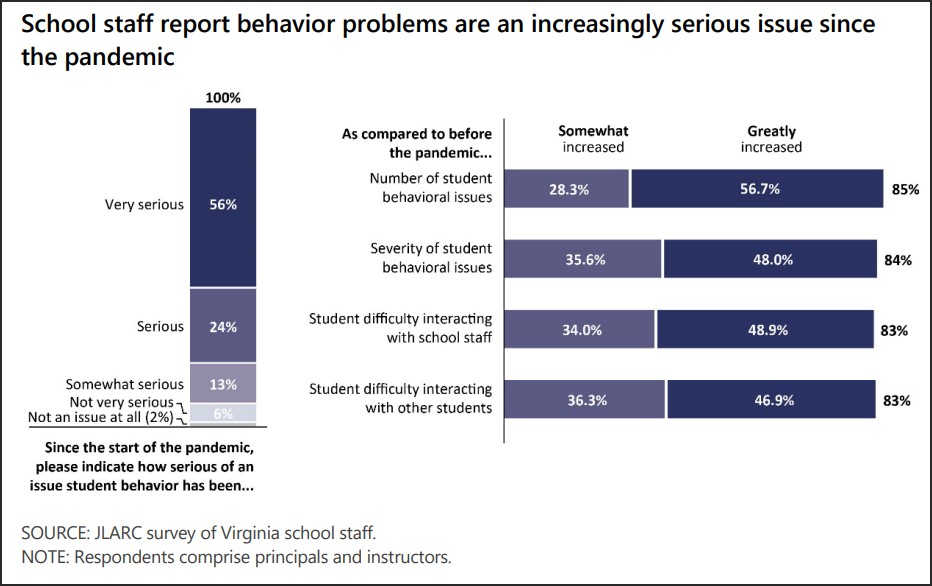

More than 56% of respondents to a JLARC survey said student behavior was a “very serious” problem, and another 24% said it was a “serious” problem. It exceeded other issues such as teacher compensation, student academic progress, lack of respect from parents, and concerns about mental health.

What’s more, concluded JLARC, student behavior appears to be worse than before the pandemic: “85 percent of school staff believed the number of student behavioral issues had either greatly or somewhat increased.” Teachers and other school staff shared the sentiment.

In explaining the collapse of discipline, the study said:

Principals and teachers cited months spent out of the physical classroom as the main reason for the increase in student behavior problems. A principal explained: “Part of it is because students missed out on two years of [behavior] training provided by faculty.” Many students had insufficient adult guidance and support at home during remote learning, further contributing to declines in student behavior. A high school teacher shared: “The students came back from a place where they were left to do what they wanted when they wanted.”

Behavioral issues were tied to two other phenomena studied by JLARC: a doubling in the rate of chronic absenteeism and increasing anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and other forms of mental illness.

Misbehaving students are more likely to struggle academically but they also distract other students. States the report: “Extreme cases of poor behavior can even make other students feel less welcome or safe in their school environment, which negatively contributes to their ability to be engaged and learn.”

There is a widespread expectation that behavioral issues will recede somewhat as students acclimate themselves to school schedules and educators reassert control over the school environment, JLARC said.

In Virginia’s locally administered K-12 system, the state has “relatively limited influence” over student behavior in classrooms, JLARC said. The job of maintaining discipline falls to local schools boards, school leadership, teachers and parents. A common response among school districts is to hire more “behavioral staff.”

JLARC cited the state’s Virginia Tiered System of Supports (VTSS) guidelines as a possible solution to behavioral issues. VTSS provides “support, technical assistance, and coaching for school staff to help divisions reduce disruptive classroom behavior.” VTSS has trained staff from 664 schools in 65 divisions, but there is considerable unmet demand. One state-level option would be to increase funding for the training.

Bacon’s bottom line: The JLARC study makes a useful contribution to the public discourse by documenting the extent of the breakdown in student behavior. But I’m dubious about its policy recommendations. The report says nothing about cell phones, which a massive body of anecdotal evidence suggests contribute to a wide range of behavioral problems from classroom distraction to bullying and fights. And the VTSS solution, of course, requires spending more money to train teachers and staff in the latest fashion in “progressive” thinking.

Here’s another idea. It’s tried and tested, and I’ll bet some school districts still use it: set clear lines of what constitutes acceptable behavior, and then enforce them. Even if it means dishing out more punishments and sanctions.

Every parent knows: adolescents push the boundaries of acceptable behavior. If parents don’t draw a clear line, adolescents keep pushing. Parents who engage in ceaseless negotiations over the line eventually find that the line dissolves and the crises never end. Basically, the VTSS methodology institutionalizes the approach of endless negotiation.

There are no easy answers of course. To a significant degree, student misbehavior is rooted in the permissiveness of American parental culture, the social breakdown of lower-income households, and the insidious effects of social media. Schools can’t fix those broader social ills. But they can set standards of behavior, enforce them, and thereby create islands of order in a society where all norms appear to be breaking down.