by James A. Bacon

The Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) has published a new report that finds that Black and Hispanic drivers in Virginia are more likely to be stopped than Whites, and they are more likely to be searched and arrested.

However, the report also says there isn’t enough data to draw definitive conclusions about bias in policing. “This analysis does not allow us to determine the extent to which these disparities may or may not be due to bias-based profiling or to other factors that can vary depending on race or ethnicity,” it states.

Veteran reporter David Ress makes that caveat very clear in the third paragraph of his story in the Richmond Times-Dispatch today, but he then goes on to highlight quotes by House Minority Leader Don Scott Jr., D-Portsmouth, Delegate Jeff Bourne, D-Richmond, and Senator Mamie Locke, D-Hampton, blaming racism.

“Obviously, bias is still a factor. It’s disingenuous not to arrive at that conclusion,” said Scott. “This is a historical and empirical truth. The data today validates the lived experiences of Black and brown Virginians.”

“We know that our commonwealth and our country have a history of racially biased policing, and we can’t eliminate that as a cause for these discrepancies,” said Bourne. “As legislators, our next step needs to be interpreting this data and working to address the reasons why police are making racially disproportionate stops.”

Said Locke: “I’m a little bit baffled as to why they don’t understand the reason behind the data.” The disparities can’t be explained as reflecting anything but drivers’ race or ethnicity, she said.

Crying racism has become the reflexive response to every statistical disparity between racial/ethnic groups in every field and endeavor. Perhaps racism, either overt or unconscious, actually is a factor in the differing traffic-stop rates. I don’t rule out the possibility. But it is reckless and inflammatory in our racially polarized society to jump to such a default explanation without considering other explanations.

Racial/ethnic groups vary significantly by age, for example. Older drivers (at least those under 80 or so) are widely acknowledged to be safer drivers. More affluent, better-educated people also tend to be better drivers. Racial/ethnic groups vary by age, socioeconomic status and education. If African American drivers skew younger, poorer, and less educated — which they do — that could go a long way toward explaining the disparities in being pulled over for traffic offenses. Racial/ethnic populations also vary by behavior, with risk factors ranging from driving under the influence to wearing seat belts, from speeding to fleeing the police in cars.

The report notes, for example, that drivers in the high-risk age group of 15 to 34 comprise 47.9% of White drivers stopped but 55.0% of Black and 57.6% of Hispanic drivers. Scott, Bourne and Locke indicate no awareness of such nuances. The media accords them the privilege of alleging bias without proof. For them, the racism is presumed.

The data

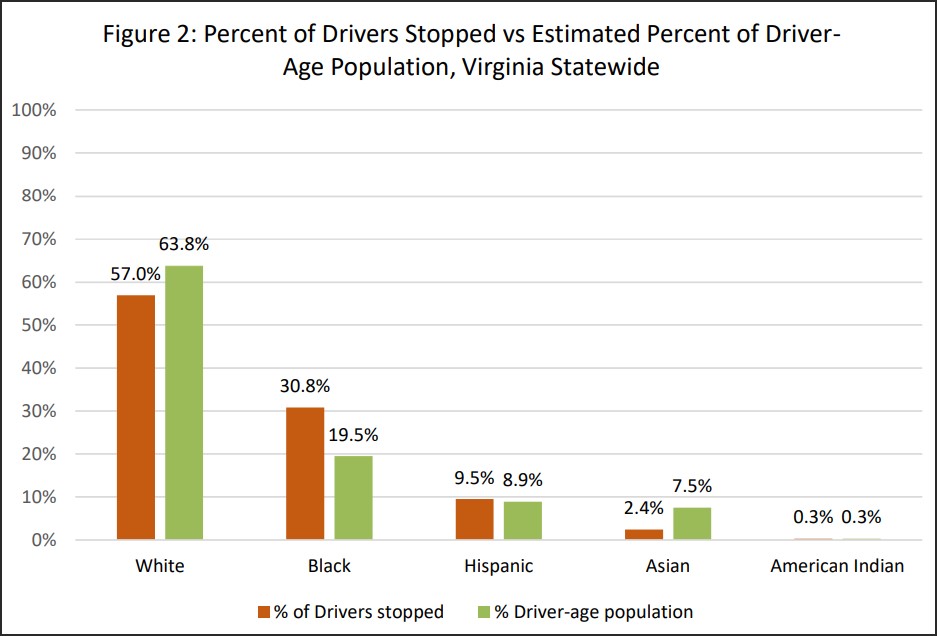

Here is the raw data comparing the race/ethnicity of drivers stopped by state and local police in Virginia.

A couple of points stand out here. True enough, the percentage of Blacks stopped exceeds their percentage of the driver-age population by 30.8% to 19.5%. But does the alleged bias extend to “brown” people, as Scott alleges? Well, Hispanics are only marginally over-represented in traffic stops — 9.5% of the stops compared to 8.9% of the population.

And how about “Asians,” a diverse group that includes both light-skinned East Asians and darker-skinned South Asians? Asians are dramatically under-represented. If systemic racial bias is at work, how come Asians are so rarely stopped for traffic violations? Is the bias of Virginia cops carefully calibrated so they are most likely to stop dark-skinned African Americans, less inclined to stop brown-skilled Hispanics, and even less likely to stop dark-skinned Asians? Or is it possible for a variety of reasons related to average age, income, education level and sub-culture, that Asians are just better drivers than everybody else — just as they are better students, earn higher incomes, and suffer from fewer social pathologies?

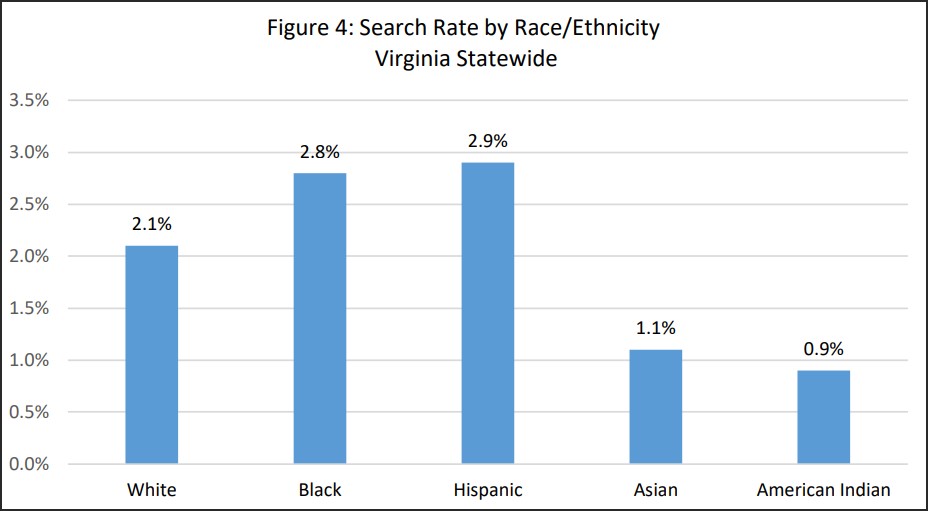

The DJCS report also shows the percentage of drivers by race/ethnicity whose cars are searched during a traffic stop. The number is higher for Blacks and Hispanics than it is for Whites, but significantly lower for Asians and American Indians.

However, an unknown factor is the extent to which Blacks might be more likely to be searched because police are more active in high-crime neighborhoods where they are more actively looking for lawbreakers.

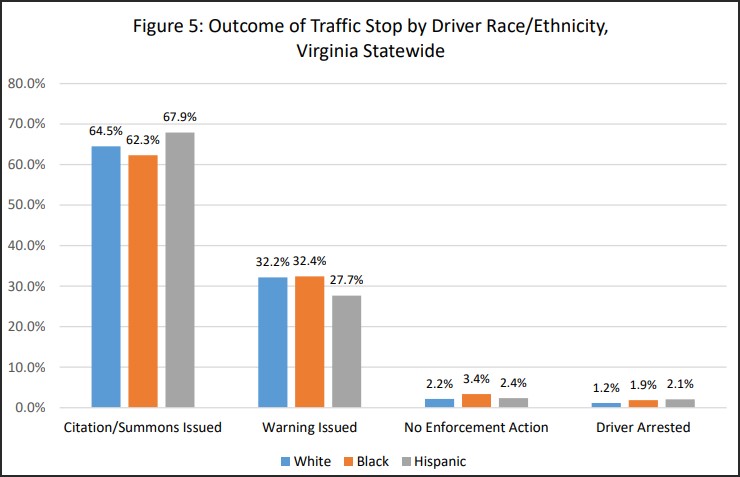

Here is the summary of traffic stop outcomes — citations, warnings, arrests, and no-enforcement actions.

The racial/ethnic disparities in outcomes are negligible. Actually, Black drivers are marginally less likely to be issued a citation or summons than Whites, and more likely to get away with a warning. Although Blacks are somewhat more likely to be arrested in a stop — possibly due to heightened policing in high-crime neighborhoods — they are also more likely to be let off with no enforcement action of any kind.

The caveats

The DJCS takes great pains to emphasize that the report findings should be interpreted with caution.

Although this analysis identified disparities in traffic stop rates related to race/ethnicity, it does not allow us to determine or measure specific reasons for those disparities …. Other factors include differences in locations where police focus their patrol activities, differences in underlying regional populations, differences in driving patterns among individuals, and the lack of a scientifically established baseline for determining the number of drivers in each racial/ethnic group who are on the road and subject to being stopped while driving.

The analysis of racial disparity is a complex field with many potential contributing factors…. But data on these factors are now unavailable to DCJS. Factors like the race of the officer performing the stop, agencies policies and community priorities driving enforcement patterns, and police report narratives outlining legal justifications for stop, search, and arrest can all inform stop patterns but are not captured in the current Community Policing Act data….

Any disparities identified herein should not be construed as proof of biased policing or of accounting for unmeasured factors which may contribute to disparities identified in this report.

Behavioral explanations

An alternative explanation to systemic bias in policing is that the behavior of different sub-populations varies. It so happens that the Governor’s Highway Safety Association (GHSA) explored some of these differences in a June 2021 study of fatal automobile accidents, “An Analysis of Traffic Fatalities by Race and Ethnicity.”

As it turns out, the hands-down worst drivers in the country as measured by fatal traffic deaths are American Indians — they are twice as likely to die in traffic accidents than Blacks, almost three times as likely as Whites, and nearly 10 times as likely as Asians. (I suspect that there is wide variability among different Indian tribes — the data indicates that Virginia Indians are as safe or safer drivers than other Virginia motorists.)

Fatal accidents invariably involve one type of traffic violation or another. The reason it is useful to look at them is that accidents almost always occur before the police get involved, hence disparities in frequency can safely be attributed to drivers, not police bias.

A major contributor to fatal accidents is speeding. American Indians had the highest rate of fatalities due to this cause — 42.8 per 100,000 population. The Black rate for speeding-related deaths was 20.1. per 100,000 compared to 13.9 for Whites, 13.8 for Hispanics and 3.8 for Asians. Speeding is one of the most common reasons for police to stop motorists. If Blacks are more likely to drive at excess speeds, it stands to reason they are pulled more frequently.

Although the number of such deaths is much smaller, Blacks are more likely to die in incidents involving police pursuit — 1.6 deaths per 100,000 compared to 0.4 deaths for Whites and 0.1 deaths for Asians.

Another behavioral difference is that Whites are slightly more likely than Blacks to experience fatal accidents during the day — 29.3 per 100,000 compared to 25.2 — but Blacks are almost twice as likely to suffer fatal accidents at night — a difference of 40.4 per 100,000 compared to 23.3. I can’t say if the daytime/nighttime difference in fatal accidents has any bearing on traffic stops. It would if police patrol more actively at night, but that point has not been demonstrated. The GSHA speculates that the disparity might be attributable to differences in night-time street lighting. Whatever the truth of the matter, it indicates how extraneous factors unrelated to policing can have a bearing on traffic outcomes.

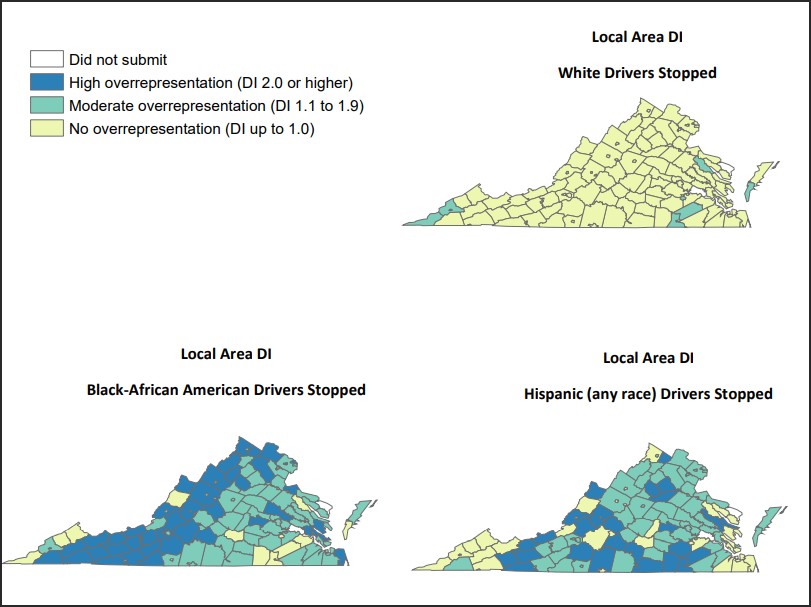

There is one set of data, however, that bears looking into: geographic variations in traffic stops. The disproportion of traffic stops is by far the highest in rural western Virginia, where the population and law enforcement authorities are predominantly White. I’m not saying this disparity does indicate bias. But it’s worth taking a closer look.

In the grand scheme of things, though, the absolute number of Blacks being stopped in Western Virginia is likely very low compared to the major population centers where most Blacks live. So, this data, though it looks dramatic when displayed on a map, may have little affect on the overall statistics.

In sum, the issues here are far more complex than Scott, Bourne and Locke seem willing to acknowledge for quotation in the newspaper.

Before drawing firm conclusions, the authors of the GSHA report recommend collecting more data:

- the time of day that traffic stops are made;

- collecting more definitive data on race/ethnicity, age, and gender of drivers;

- results of searches for contraband;

- stops in which an officer could observe the driver’s race/ethnicity and those in which they could not;

- race/ethnicity of the officers making the stop;

- and more.

I agree with the GSHA recommendations. We want to get to the truth of the matter. It’s wrong to sweep evidence of racism under the rug; we want to identify it and correct it where it exists. Likewise, it is wrong to unfairly accuse police of systemic bias, which contributes to poor police morale and burdens Black citizens with a fear that may have no basis in reality. Let’s find out if bias exists, where it exists and how acute it is rather than indulge in blanket accusations.