On Friday, the VDH reported on its COVID-19 page that 30 individuals had been identified as having contracted the coronavirus and 10 had been hospitalized. As of Saturday, VDH was stating that the number of cases had increased to 41, but it no longer provided the number of hospitalizations. The website offered no explanation for the omission. The metric is a critical one, and the public needs to know it.

As we have seen in China and Italy, hospital systems have been overwhelmed as the epidemic progresses. When hospitals run out of beds and staff to treat the afflicted, doctors go into triage mode and let some people die in order to treat those with a better chance of surviving. Virginians have every reason to wonder if a similar fate awaits the Old Dominion. Do we have enough hospital beds? Are we making the proper preparations, such as arranging for overflow facilities?

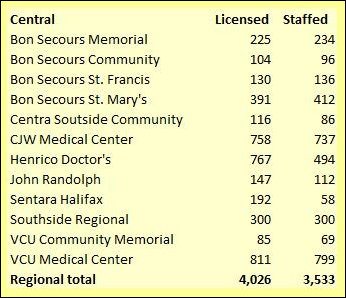

I addressed that question briefly in a blog post last week, including some numbers for hospitals in Central Virginia. This weekend, I’ve taken a more comprehensive look, and to my admittedly untutored eye the numbers look worrisome.

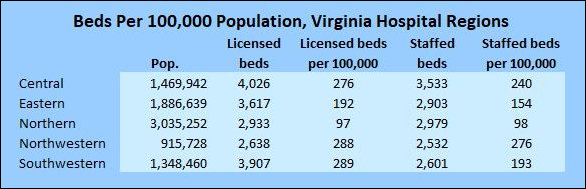

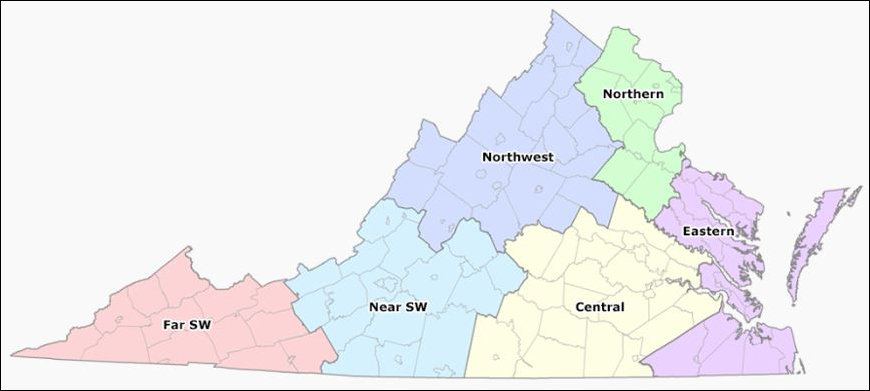

When the crunch comes, it appears that it will hit Northern Virginia the hardest. Whether you’re counting licensed beds or staffed beds, Virginia’s most populous region has the least hospital capacity of the six regions that Virginia Health Information uses to group hospitals — only 98 beds per 100,000 population.

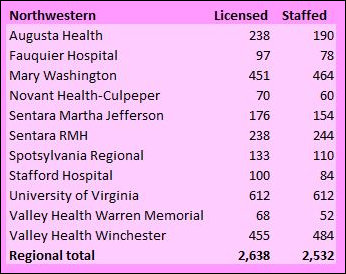

By contrast, the best place to be is in the state’s Northwestern region, which encompasses a triangle from Charlottesville to Staunton to Winchester (as seen in the map below). That region has 276 beds per 100,000.

The Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia estimates that Virginia’s 2020 population is 8.6 million. If the disease follows the same path as it has in many (but not all) other countries, 30% to 40% of the population could be affected. Nobody knows for sure, and estimates very widely. The Governor of Ohio said on television this morning that the percentage could run as high as 70%. But I’m trying to be conservative here to avoid accusations of being an alarmist. A 30%- to 40%-estimate implies that something on the order of three million Virginians could contract the disease. Of those, some 10% could require hospitalization. Again, nobody knows the percentage that will wind up in the hospital, but that’s an educated guess based on what we’ve seen in other countries. In sum, it is not unreasonable to expect that Virginia acute-care hospitals could be required to treat some 300,000 coronavirus patients suffering severe symptoms.

The Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia estimates that Virginia’s 2020 population is 8.6 million. If the disease follows the same path as it has in many (but not all) other countries, 30% to 40% of the population could be affected. Nobody knows for sure, and estimates very widely. The Governor of Ohio said on television this morning that the percentage could run as high as 70%. But I’m trying to be conservative here to avoid accusations of being an alarmist. A 30%- to 40%-estimate implies that something on the order of three million Virginians could contract the disease. Of those, some 10% could require hospitalization. Again, nobody knows the percentage that will wind up in the hospital, but that’s an educated guess based on what we’ve seen in other countries. In sum, it is not unreasonable to expect that Virginia acute-care hospitals could be required to treat some 300,000 coronavirus patients suffering severe symptoms.

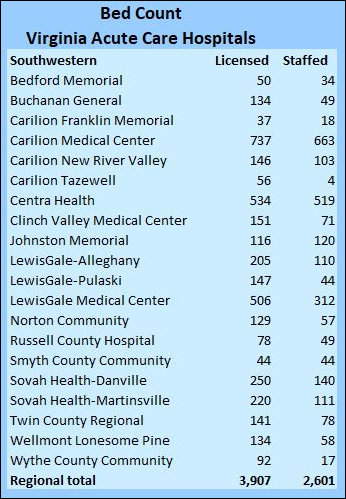

According to Virginia Health Information, Virginia’s acute care hospitals have 17,100 licensed beds. Of those, 14,600 are staffed. In other words, state hospitals have more beds than doctors, nurses, and other health professionals to staff them. (Staffing levels are a separate issue, which I will defer to another discussion.) I can find no data on the number of intensive care units (ICUs) or ventilators, both of which are critical for treating patients with severe respiratory ailments, in the state.

According to Virginia Health Information, Virginia’s acute care hospitals have 17,100 licensed beds. Of those, 14,600 are staffed. In other words, state hospitals have more beds than doctors, nurses, and other health professionals to staff them. (Staffing levels are a separate issue, which I will defer to another discussion.) I can find no data on the number of intensive care units (ICUs) or ventilators, both of which are critical for treating patients with severe respiratory ailments, in the state.

I’m making somewhat arbitrary assumptions here — pick your own values for the variables and make your own estimates — but let’s assume somewhat optimistically that Virginians’ social-distancing practices dampen the geometric rate of increase of the COVID-19 virus and that the surge of patients into hospitals is spread over four months. Let’s also assume that the average patient is hospitalized for ten days, suggesting that a hospital bed can accommodate 12 patients on average over a four-month period. That would imply the need for 25,000 hospital beds — the equivalent of 290 beds per 100,000. That actually understates the case because it doesn’t account for peak demand for beds at the height of the epidemic, but I’m trying to keep things simple here.

I’m making somewhat arbitrary assumptions here — pick your own values for the variables and make your own estimates — but let’s assume somewhat optimistically that Virginians’ social-distancing practices dampen the geometric rate of increase of the COVID-19 virus and that the surge of patients into hospitals is spread over four months. Let’s also assume that the average patient is hospitalized for ten days, suggesting that a hospital bed can accommodate 12 patients on average over a four-month period. That would imply the need for 25,000 hospital beds — the equivalent of 290 beds per 100,000. That actually understates the case because it doesn’t account for peak demand for beds at the height of the epidemic, but I’m trying to keep things simple here.

Virginia has 17,100 acute care beds total. Nationally, about 70% of acute-care beds are utilized on average. Let’s assume that by restricting the admission of patients for discretionary procedures hospitals can free up 20% of the beds. (Another arbitrary assumption, but I’m trying to isolate key variables here. Feel free to plug in your own numbers.) Based on these assumptions, the number of beds in Virginia available for coronavirus patients would be roughly 8,500 — one third the number needed.

Virginia has 17,100 acute care beds total. Nationally, about 70% of acute-care beds are utilized on average. Let’s assume that by restricting the admission of patients for discretionary procedures hospitals can free up 20% of the beds. (Another arbitrary assumption, but I’m trying to isolate key variables here. Feel free to plug in your own numbers.) Based on these assumptions, the number of beds in Virginia available for coronavirus patients would be roughly 8,500 — one third the number needed.

There’s a good-news story and a bad-news story within those numbers. The gap in hospital beds is not spread evenly across the state. The Northwestern and Central regions come close to my back-of-the-envelope guesstimate of how many acute care beds will be needed. The hospital-capacity crisis will likely be less severe in those regions. But the Northern Virginia and Eastern region (mainly Hampton Roads) fall scarily short.

There’s a good-news story and a bad-news story within those numbers. The gap in hospital beds is not spread evenly across the state. The Northwestern and Central regions come close to my back-of-the-envelope guesstimate of how many acute care beds will be needed. The hospital-capacity crisis will likely be less severe in those regions. But the Northern Virginia and Eastern region (mainly Hampton Roads) fall scarily short.

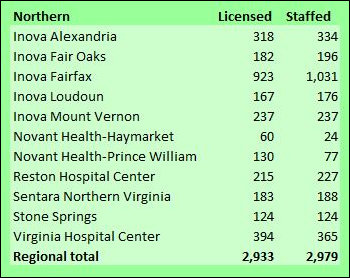

Measured by the number of hospital beds per 100,000 population Northern Virginia’s health system runs lean and mean. The region with three million population has roughly 3,000 licensed beds in acute-care hospitals and it staffs every last one of them. (See the green table above.) Indeed, according to VHI data, Northern Virginia hospitals somehow manage to staff a few more beds than they’re licensed for.

Running lean on the number of hospital beds helps contain health care costs, but it provides little capacity to fall back upon in the case of an epidemic. Northern Virginia has no inventory of empty beds to accommodate a flood of coronavirus patients. With 98 beds per 100,000, Northern Virginia has about one-third the number it needs to handle the epidemic load that I have postulated here.

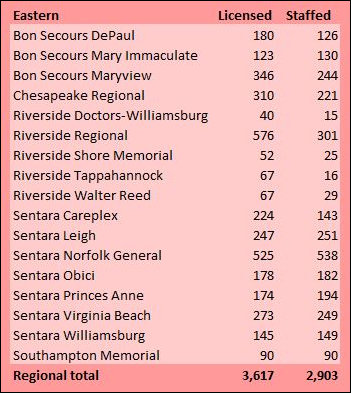

With 154 beds per 100,000, the Eastern region has about half the number it needs.

To repeat: I have tried to make these estimates conservative. The beds-per-100,000 ratios for those two regions are low by national standards, and even lower by the standards of other industrialized nations. The average number of “curative care” beds for the U.S. as a whole was 277 per 100,000 population in 2016, according to OECD data. Thirty-one other countries had a higher proportion of curative care beds. Italy, for instance, had 317, yet its health care system has been overwhelmed. (I’m not clear what the difference is between a “curative care” bed and an “acute care” bed, so such comparisons must be made with caution.)

Needless to say, the Virginia Department of Health has much more authoritative epidemiology models and better data than I can provide here. Perhaps we can take heart that no public health official or hospital official in Virginia has expressed public concern that there might be an insufficient number of hospital beds. Indeed, Governor Ralph Northam has assured Virginians that the state has a plan in place to confront the virus. However, I have seen no hints in the public domain — announcements, press releases, news articles — that anyone is taking concrete action to handle an overflow of coronavirus patients, should it occur.

If hospitals are turning away patients for elective procedures, they are doing so without fanfare. A good modeling system should be able to predict when the epidemic will reach a critical stage — say, early April. I have not heard hospitals appeal to the public to reschedule elective procedures during that period. Meanwhile, if hospitals and public health authorities are lining up space, cots and medical equipment for pop-up facilities like those seen in China, they are doing so quietly behind the scenes. I, for one, would feel reassured to know that efforts are taking place to deal with a worst-case scenario. Such precautions would seem to be mandatory in Northern Virginia with its low ratio of hospital beds. The fact that we’re hearing nothing should make you queasy. Either we’re experiencing a failure in the plan or a failure to communicate.