by Jock Yellott

As an August vacation from current events, let’s explore Virginia’s Right of Rebellion — and the question of Confederate treason.

It’s in our state constitution Bill of Rights: “Whenever any government shall be found inadequate or contrary to [the benefit, protection, and security of the people] a majority of the community hath an indubitable, inalienable, and indefeasible right to reform, alter, or abolish it, in such manner as shall be judged most conducive to the public weal. Virginia Constitution Art. I §3 (June 12, 1776).

Virginia’s Constitution was no anomaly.

When the American colonies seceded from England in 1776, and afterwards for the next three quarters of a century until 1860, most state constitutions in their Bill of Rights or Preamble reserved to the citizens the right to abolish their own governments. A representative sample: the original colonies Virginia, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Georgia, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, and later (when added to the union) the states of Texas and Maine.

Some, like New Jersey and New Hampshire, hedged their bets by saying rebellion was only temporary: “protesting and declaring that we never sought to throw off our dependence upon Great Britain, but felt ourselves happy under her protection, while we could enjoy our constitutional rights and privileges. And that we shall rejoice if such a reconciliation between us and our parent State can be effected ….”

Jefferson was right: monarchists lurked among us. And, judging from the rest of the state constitutions, he was only half-joking when advocating another revolution every twenty years.

Prominent lawyers including both Jefferson’s arch-nemesis Alexander Hamilton and later Abraham Lincoln can be found arguing both sides of the right of rebellion.

Hamilton in the Federalist Papers warned only a strong Union could prevent fractious states from fragmenting the country into pieces, to be picked off by foreign nations one by one. Yet Hamilton’s own Federalist party in the 1790’s began organizing for New England’s secession, fearful of Jefferson’s egalitarian fanaticism, that he would bring the French Revolutionary guillotine to America.

Secession gathered steam after President Jefferson ordered an embargo against trade with England, utterly destroying American merchants but little annoying the British. Jefferson got a letter from one despairing merchant whose child starved to death, because the father could not feed his family. The embargo and the threat of New England’s secession fell by the wayside with the end of Madison’s feckless War of 1812.

In the House of Representatives in 1847, supporting Texas’s secession from Mexico, none other than Abraham Lincoln said, “[A]ny people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up, and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better ….” Lincoln appears to have changed his mind later.

In the Civil War, the seceding Virginians asserted they were the rightful heirs of the Founders: Washington, Madison, and Jefferson especially. And like Benjamin Franklin, they knew what failure meant. Franklin reputedly remarked at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “We must all hang together, or most assuredly we will all hang separately.”

But very few, unlike Jefferson Davis, actually did face treason charges following the Civil War. The charges were dropped since Davis could argue he hadn’t been a United States citizen those four years. Also, if tried in Virginia, no jury would convict him. The general sense was: time to put the Recent Unpleasantness behind us.

Those now railing at statues of Confederate Generals Lee or Jackson as effigies of traitors are nurturing the anger to keep the anger alive longer than the folks who actually fought them. “Waving The Bloody Shirt,” it was once called.

The right of rebellion can be traced back to the literature of classical Greece and Rome, revisited in the 17th Century writings of John Locke. Locke’s views reflect the turbulent times when Oliver Cromwell overthrew the monarchy and had King Charles I beheaded. After that, England was briefly a Puritan Commonwealth (from which “Commonwealth of Virginia” derives).

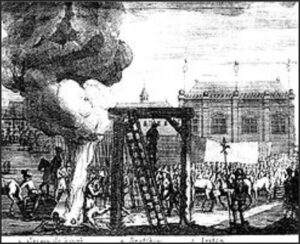

After Cromwell died and England restored the monarchy, we note in passing, Cromwell’s (or somebody’s) corpse was dug up, charged with treason, and hanged. The Woke charging dead Confederate officers with treason follows the tradition of vindictive empty gestures.

Locke’s Social Contract theory, along with the concomitant right of rebellion if the contract is breached, was imported and popularized in the American colonies. Locke’s theory undergirds the Virginia Constitution of 1776, and in turn James Madison’s first draft of the federal constitution in 1787.

But let’s get real — can you use your Virginia constitutional right of rebellion, say, to beat a parking ticket? Arguing to the judge (never EVER debate with the police officer, only make your case later to an impartial judge): “Your honor, the majority in my car exercised our indubitable, inalienable, and indefeasible right to abolish two hour parking, for the public weal.”

No. Depend on it: a judge won’t declare Virginia law abolished and himself out of a job. Only one Virginia case has cited this provision. The case considered the people’s sovereign right to amend the constitution, curtailing poll taxes so World War II soldiers could vote in the 1945 elections. Minor reform. But abolishing the regime?

In truth this Virginia “right” of rebellion has only ever been enforced by force of arms (twice: 1776 and again in 1860). Not a legal right, in the sense of briefed and argued in court, closely or broadly read, stretched, shrunk, or circumvented. More a recital of fighting faith.

And as Hamilton cautioned, a right of rebellion doesn’t work as a principle of government. It’s self-destructive. The New York constitution had it right: in the absence of royal government the citizens have a right to create one. But some government is a necessity, even if a necessary evil as the Founders seemed it. We are better off within the rule of law than without.

Still, the Right of Rebellion in the Virginia constitution is a rejoinder to those who charge treasons against Generals Lee or Jackson. Even if it’s just a leftover in the law, a picturesque historical relic as a reminder of the past. Sadly, thanks to the Woke, not many of those remain in Virginia.

Jock Yellott, a retired lawyer in Charlottesville, is an occasional contributor to Bacon’s Rebellion.