Over the past month Del. Dave LaRock, R-Hamilton, has criticized the state’s Smart Scale scoring system for allocating transportation dollars. By law, he says, the system is supposed to prioritize congestion mitigation. But the latest round of allocations was biased heavily in favor of land use and economic development. As a result, a Metro station project near the planned Amazon HQ2 project received funding while a Rt. 7 improvement project with greater congestion-mitigation benefits did not. This year the overwhelming majority of Northern Virginia transportation funds are going to projects inside the Beltway and only a pittance to counties on the metropolitan fringe. LaRock says the system is “seriously broken.”

Over the past month Del. Dave LaRock, R-Hamilton, has criticized the state’s Smart Scale scoring system for allocating transportation dollars. By law, he says, the system is supposed to prioritize congestion mitigation. But the latest round of allocations was biased heavily in favor of land use and economic development. As a result, a Metro station project near the planned Amazon HQ2 project received funding while a Rt. 7 improvement project with greater congestion-mitigation benefits did not. This year the overwhelming majority of Northern Virginia transportation funds are going to projects inside the Beltway and only a pittance to counties on the metropolitan fringe. LaRock says the system is “seriously broken.”

Deputy Secretary of Transportation Nick Donohue defends the Smart Scale methodology. As it happened this year, yes, Northern Virginia road and highway funding did fall short. He offers two justifications. First, congestion mitigation is not the only factor considered in Smart Scale, and the other projects offered tremendous benefits in other areas. Second, Smart Scale measures congestion mitigation per dollar spent. Improvements to Rt. 7, benefiting LaRock’s Loudoun County constituents, would have ameliorated a lot of congestion, but it is also a very large, very expensive project.

LaRock has a response to that. Peculiarities in the Smart Scale methodology had the effect this year of diminishing the weight given congestion mitigation projects. The state’s top congestion-relief project, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel expansion, offered benefits so far and above all other projects that it minimized the weighting of congestion benefits for those projects.

The issues here are arcane and difficult to explain. Thus the debate boils down to he-said, she-said with LaRock and Donohue on opposite sides of the controversy. But the annual allocation of roughly $800 million yearly in transportation construction dollars is at stake. LaRock, along with Del. Tim Hugo, R-Centreville, has launched the first major challenge to the scoring system, which was designed with the hope of taking politics out of transportation decision-making.

Herewith, Bacon’s Rebellion offers a tutorial on the mechanics of the Smart Scale system, the allocation of state transportation funds, why the Crystal City project scored higher than the Route 7 project, and why LaRock thinks the methodology needs reform.

Multiple buckets of transportation funds

There are multiple buckets of transportation construction funds. Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, the regions with the worst congestion, levy regional taxes that pay for regional projects. Each region has its own governing body to select projects funded with those dollars. Smart Scale is the tool used to allocate transportation projects funded by roughly $800 million in statewide revenue sources.

Under state law, 50% of the statewide dollars must be allocated proportionally to the state’s nine transportation districts. The other 50% can be allocated anywhere in the state. Smart Scale evaluates both regional priorities and statewide priorities. This year 25% of statewide transportation construction dollars was steered to Northern Virginia. Hampton Roads also won 25% ($200 million) for the bridge-tunnel project alone.

In the Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads districts, congestion mitigation is given the highest weight. Other districts weigh criteria differently, depending upon regional priorities. More rural districts, for instance, tend to give economic development higher priority.

Weighting ratios

The Smart Scale process assigns the following weights to different scoring criteria in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads:

- 45% Congestion mitigation. The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) uses a Travel Demand Model to calculate the project’s peak-period throughput in total number of people and reduction in person-hours of delay.

- 20% Land use. VDOT calculates the project’s impact on land use in regions with more than 200,000 population, recognizing that certain human settlement patterns — particularly dense, mixed-use projects — generate fewer traffic trips per household than others. Says Donohue: “The land use measure looks at how can we facilitate more growth that has a lower impact on the transportation network.”

- 15% Accessibility. Accessibility measures a project’s ability to increase the access to jobs of people generally, and disadvantaged populations specifically. A GIS tool calculates the number of additional jobs accessed per person.

- 10% Environmental quality. This yardstick measures a project’s impact on air quality, wetlands and other environmental factors.

- 5% Safety. This measure estimates a project’s expected impact on the number of moderate injuries, severe injuries, and fatalities.

- 5% Economic development. This category measures the square footage of commercial/industrial space supported, improvements to travel-time reliability, and tons of freight impacted. The economic impact improves with proximity to ports, airports, warehouses, and intermodal facilities.

After crunching the numbers and getting values for six categories and 14 sub-categories, the Smart Scale model produces a “normalized measure” for each. This is critical in the LaRock-Donohuse debate. According to VDOT’s “How to Read a Scorecard,” the value is “normalized as a percentage of the highest Measure Value in that year’s cohort of projects.” Thus, if a project garners an exceptionally high score for congestion mitigation — 100 in the case of the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel — all other projects will measured as a percentage of that high score, giving them relatively low normalized measures.

The normalized measure is then multiplied by its weight (45% in Northern Virginia in the case of congestion mitigation projects) to yield a “factor value.” Then follows a series of synthesized values including weighted factor value, project benefit, Smart Scale Cost, and Smart Scale score.

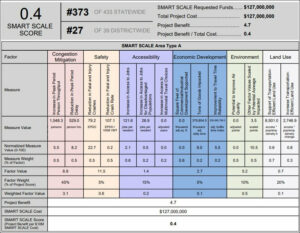

Route 7 versus Crystal City Metro

VDOT publishes a scorecard and detailed statistics for each project. The scorecard for the Route 7 project in Loudoun County would make safety and operational improvements between Route 9 and the Dulles Greenway toll road. The project would cost an estimated $127 million dollars. The methodology estimates that rush hour capacity would increase by 1,548 persons daily and the rush hour delay would be reduced by 529 person hours. But by comparison to the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, Route 7 warrants a “normalized measure value” of only 5.5 on a 100 scale, thus severely diminishing the weight given to the project’s most important benefit.

As this low score flows through the scoring system, the project ends up with a 4.7 project benefit and a Smart Scale score (project benefit per $10 thousand cost) of 0.4.

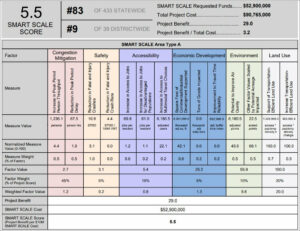

The Crystal City Metro project would construct a second entrance to the Crystal City Metrorail Station in Arlington. The project cost is $90.8 million, $52.9 million of which would be funded through Smart Scale. The project provides less congestion mitigation than Route 7 — a rush-hour capacity increase of 1,236 persons and only 67.5 person-hours saved. But the project scores extremely well in economic development (primarily square footage of office space supported), the environment, and land use. Indeed, for land use, the Metro project scores 100.

As these scores flow through the Smart Scale, the project benefit is 29.0 and, adjusted for benefit per $10 thousand) it rates a 5.5.

Says Donohue: “What are the congestion benefits relative to the costs? The two projects have similar congestion benefits. But Crystal City scores higher on environmental and land use, promoting growth in a way that will reduce the impact on the transportation network in the future.”

Funding was tight for Northern Virginia this round. The Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel expansion snagged $200 million, or about half of every transportation dollar that could be allocated anywhere in the state. Such an anomaly probably won’t happen again next year, says Donohue. Even if the Route 7 project didn’t make the cut this year, eight of the top 10 congestion-mitigation-per-dollar projects in Northern Virginia did get funding. “How has legislative intent been tossed out the window?”

Daniel Davies, LaRock’s legislative assistant, says LaRock asked Donohue to treat the bridge-tunnel as the outlier it is, score it separately, and then to res-core all the Northern Virginia projects. “Sure, go ahead and fund the HRBT, but don’t kill all the other congestion-mitigation projects statewide.”

Davies also contends that the “land use” and “accessibility” categories overlap to a large degree — both give a bonus to density — and should receive less than a combined 35% weight. If Smart Scale treated the bridge-tunnel separately as an outlier and weighted congestion mitigation 65% for Northern Virginia, he says, Smart Scale would have provided funding for the Route 123 interchange project in Prince William County.

LaRock is not the only elected official to complain about Smart Scale. He’s just the one to stick out his neck and challenge the methodology publicly. Says Davies: “The Secretary [of Transportation]’s office caught flack from all around the state.”