Virginia’s legislative audit agency started its most recent analysis of Virginia’s economic development incentive grant programs with an assumption boosters would quickly dispute – that 90 percent of the economic activity they produce would have happened anyway.

With that assumption baked into the data, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission found very small benefits for the various grants or tax incentives Virginia offers employers for new business locations or expansions. This year’s summary looked at $1.8 billion spent on grants or foregone through tax exemptions over eight years.

“For grants, the assumption was made that 10 percent of grant employment creation is attributable to the programs, with one exception (the Governor’s Motion Picture Opportunity Fund),” according to the full text of the JLARC report released Monday. The same 90 percent discount applied to job creation was also applied to capital investments and the tax benefits they produced. The report cites various academic studies on business location decisions as justification.

JLARC also adds a form of negative dynamic scoring to its calculation, reducing the benefits by presumed adverse impacts of the taxes used to pay for them.

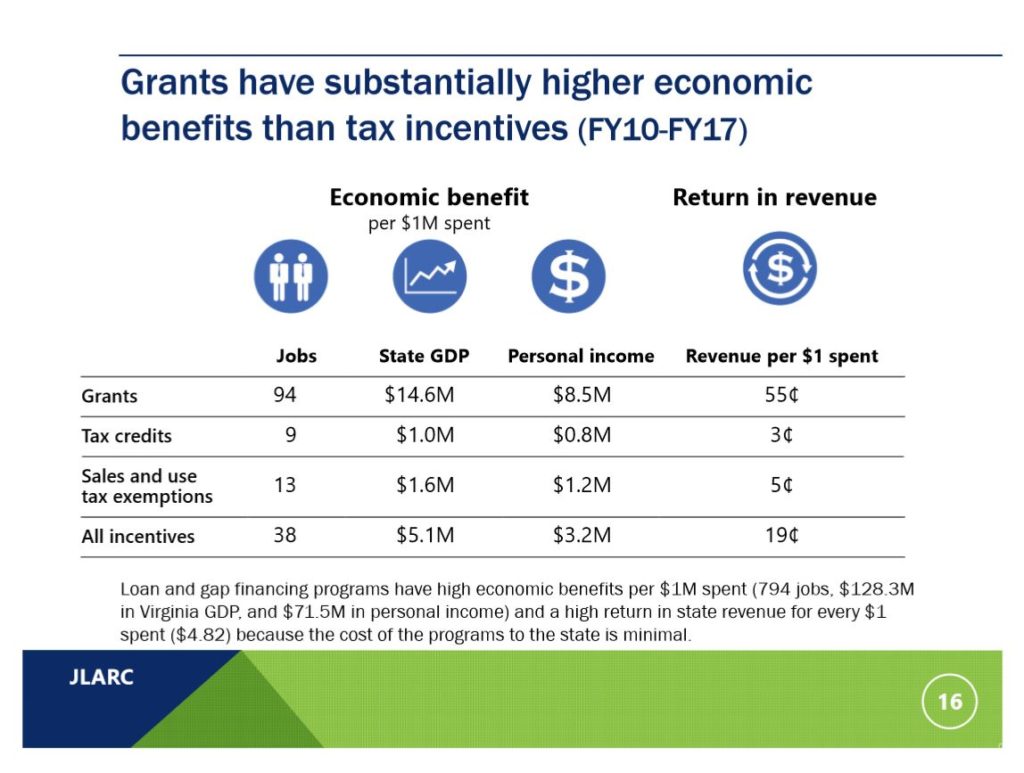

The state tax revenue generated by the state’s various grant programs was measured at 55 cents for every dollar in grants given by the state. The payback on various specialized tax incentives was even lower, from three to five cents per dollar, as shown in a slide from the presentation made by Ellen Miller of JLARC’s staff. The report pegged the overall return at 19 cents of state tax revenue per state dollar cost.

Revenue for the state is not the only outcome sought. The analysis also showed each $1 million in grants or tax breaks produced 38 jobs, $5.1 million in state gross domestic product, and $3.2 million in personal income, with grants performing the best among major programs.

JLARC worked with the Weldon Cooper Center at the University of Virginia on the economic benefit analysis. Similar metrics have been applied to individual programs in past analyses, but this was the first use of the methodology across the board. It provides a contrast to the high pay-off projections the state usually makes about projects receiving grants, such as the recent Amazon project package which will be debated by the 2019 General Assembly.

This JLARC report looks back at the period of 2010 through 2017, so the Amazon project is not yet part of the review. No one involved with that has indicated that Amazon was 90 percent certain that it was coming to Virginia before any incentives were offered. As Miller noted in an email after her presentation, the Virginia Economic Development Partnership numbers attribute 100 percent of the outcomes to the incentives.

Some major economic development programs are not included in the analysis because they are relatively new. The GO Virginia program, managed by a group of business executives, is probably the highest-profile activity not yet subjected to JLARC review, along with a package of future grants designated for Newport News Shipbuilding as it starts construction of a new class of Navy submarine.

Another shipyard grant program, which financed construction of a new Apprentice School, is reported to have cost $32,000 per created job, the most expensive for the period covered by the report. The headline “cost per job” will be an element in the coming Amazon debate.

Much of the report’s focus is on sales tax exemptions or tax credits offered for specific industries or activities, with JLARC again concluding that in general they do not produce a major revenue return for the state. The largest tax credit was $82 million paid out over the period for utility usage of Virginia-mined coal, and the largest sales tax exemption was $285 million in tax breaks for data centers.

The report shies away from the major sales tax exemptions which are part of virtually every state’s sales tax system, such as for services or manufacturing inputs. It focuses instead on those aimed at specific industries or activities, such as shipbuilding, nuclear repair, pollution control, air and rail carriers, railroads and motion pictures.

The exemptions are different than the credits, however. Some of them have justifications that don’t involve job creation or economic development, such the exemption for pollution control investments. The entertainment industry incentives deal with companies highly motivated in location choices by tax considerations. The state’s private ship repair operations would note they compete directly with tax-free Navy shipyards for contracts.

In analyzing the payback on the grants and tax incentives, Weldon Cooper has added another factor seldom mentioned: It estimated and accounted for “reduction in economic activity because of the tax increase to pay for the sales and use tax exemptions (or grants).” This is the kind of dynamic scoring of opportunity cost that is rarely used by the state. In fact, not everybody on the state payroll is willing to admit that raising or lowering taxes has an inverse impact on employment and gross domestic product.

Weldon Cooper estimated jobs added under the grant programs, but then subtracted a number of jobs from each year’s total as jobs lost because other taxpayers had less money. It also subtracted millions in state gross domestic product and personal income as opportunity costs, lowering the cost-benefit result for grants in general. The details on all this are buried deep in the appendices.

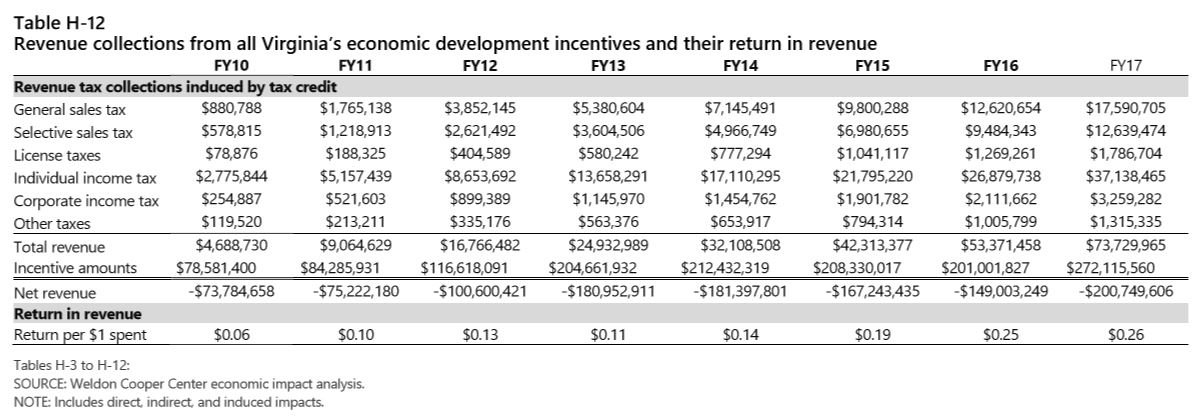

Lumping all the economic development programs and tax breaks together in the final table (above), JLARC and Weldon Cooper estimated $74 million in state tax revenues generated during 2017, at a cost of $272 million in grants paid or taxes not collected. That works out to 26 cents on the dollar, which is a fine return if that is on capital you continue to hold. In this case, however, somebody else walks off with the principal.