FAIRFAX, Va. – On Friday, May 27, local father Brett Byrnes, a former military officer, dashed over to his second grade daughter’s elementary school, Greenbriar East Elementary School. The school nurse had just called to say she was out of his second-grade daughter’s dosage of Adderall, a prescription drug used to treat ADHD, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Weeks earlier, he had counted out the pills with the school health aide, Jennifer Carpenter, to make sure there was enough medicine to last through the last day of the school year, Friday, June 10. For nine months, since October, the Byrnes parents had been writing back-and-forth with Carpenter, telling her their daughter was reporting that she wasn’t getting her medicine regularly.

She kept reassuring them everything was fine, just hectic with her “kiddos.”

What they uncovered – by being caring, diligent, persistent parents who questioned the system – is that Carpenter had been allegedly stealing their daughter’s Adderall – a stimulant – and giving her Claritin, an over-the-counter medication used for allergies.

It was as much a shock to them, as it is to read.

And their daughter wasn’t alone: under the eye of school officials at their otherwise lovely local neighborhood school, where the mascot is the Roadrunner, Carpenter had allegedly stolen medicine from six other children.

It’s any parent’s nightmare: you trust the school system, and even its healthcare providers endanger the safety and wellbeing of your child.

That Friday, within hours of Byrnes’ discovery, county health officials filed a police report with Fairfax County Police Department, and the police opened an investigation, case number 20221470199, with a detective from the Major Crimes Bureau assigned to the case. Fairfax County Child Protective Services also opened an investigation and interviewed students affected by the alleged theft the following week.

But almost two weeks later, Fairfax County Public Schools hasn’t yet notified school or school district parents of this alleged serious crime. And parents of students notified aren’t satisfied with the lack of transparency on the investigation, details of any audits the school completed over the year, or solutions. I learned about this case from a parent.

“It’s truly criminal that medicine has been stolen from children. This is a systemic problem,” Byrne said to me.

‘Covering up’

The mother of a fourth grader, 10, whose Ritalin, also used for ADHD, was allegedly stolen, told me: “They can’t even find the audit documentation. It seems the school is covering up their failures.”

This case is important because it reflects the growing frustration of parents trying to advocate for the wellbeing and safety of their children, only to be dismissed, demonized as engaging in “domestic terrorism,” and even handcuffed. In Uvalde, Tex., police pepper-sprayed and handcuffed parents who were demanding action to save their children from a gunman. In neighboring Loudoun County, Va., a father, Scott Smith, was arrested after he learned his daughter had been anally raped in the girl’s restroom of her school.

Even a school district the size of Fairfax County – with a $3 billion budget – can’t get it right, raising questions about the sweeping plans for “social and emotional” intervention they seek to roll out for children. At Independent Women’s Network, where I just joined as a senior fellow in the practice of journalism, I heard from parents about this failure, and — when the system fails America’s children — we’ve got to band together to ask the tough questions and hold officials accountable. That’s what we’re aiming to help parents do at Independent Women’s Network. (Join us for free.)

That’s how I ended up outside Greenbriar East Elementary School, a lovely school in a bucolic neighborhood. I have been a parent advocate in Fairfax County for two years, and this case broke my heart for the vulnerability of children exploited.

Asked why the school system hasn’t notified school or school district parents, Fairfax County Public Schools spokeswoman Helen Lloyd directed questions to the Fairfax County Health Department. The Fairfax County Police Department said it could not respond to a public records request because the case is an open investigation. Carpenter had an out-of-office response (from 2019) on her official school email address. She couldn’t be reached at various phone numbers listed in the area for her name; a woman at one phone number hung up the phone on me when I explained why I was calling.

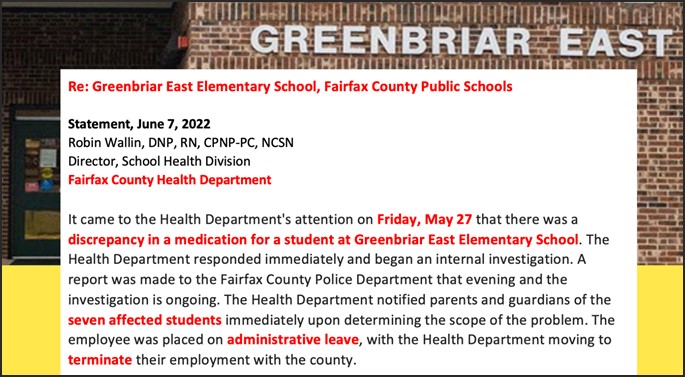

Tuesday evening, Robin Wallin, director of the Fairfax County Health Department’s school health division, issued a statement, via a spokeswoman: “It came to the Health Department’s attention on Friday, May 27 that there was a discrepancy in a medication for a student at Greenbriar East Elementary School. The Health Department responded immediately and began an internal investigation. A report was made to the Fairfax County Police Department that evening and the investigation is ongoing. The Health Department notified parents and guardians of the seven affected students immediately upon determining the scope of the problem. The employee was placed on administrative leave, with the Health Department moving to terminate their employment with the county.”

‘Diverting’ medicine

While parents districtwide don’t know about this scandal, school officials have known for days. At 6 p.m. on Tuesday, May 31, the second grader’s parents got a letter from Dr. Gloria Addo-Ayensu, the Fairfax County Health Director, notifying them that health department officials had learned there was a “discrepancy in medication” because a health department employee had been “diverting” medication “belonging to students.”

They were told their daughter’s medication “was part of this diversion,” and then a shocker: “…we have reason to believe that the employee may have on occasion given your child a generic over the counter [sic] antihistamine in lieu of her prescribed medication.”

Based on the information we have learned about the employee’s behavior and actions, we have placed the employee on administrative leave and are moving to terminate their employment with the county. We will continue to look carefully at the documentation and other information to gain further understanding about this situation. I am so sorry that this has happened, and I want to reassure you that we will do everything in our power to ensure that this kind of situation does not happen again. Keeping our students healthy and safe is a priority of the health department.

Forwarding the letter, Wallin wrote: I am so very sorry that this happened.”

The second-grader’s rocky school year was now making sense to the Byrnes. Two weeks earlier, her mother told the principal in an email that they were considering holding their daughter back because she was falling behind in school.

The system had failed.

Across the country, including Fairfax County, Va., school policies cover how to secure and maintain prescription medications that students take while at school. Health aides and nurses keep medication in a drug locker that can only be opened by certain school employees who administer the prescriptions to students. To be a health aide, you have to have a high school degree or equivalent, and they are paid about the rate of bus drivers; a sign outside the school advertises a driver’s salary at $22.91 per hour.

The euphemism of drug “diversion” is a problem nationally. In 2018, a nurse at Station Camp High School in Sumner County, Tenn., was charged with three counts of theft for stealing 82 medication doses from at least three students, but The Tennessean reported in August 2019 that “her case wasn’t widely known until it was revealed in public records obtained by the Tennessean.”

In October 2019, a nurse at Barber Middle School in Cobb County, Ga., was fired after she stole 209 pills used to treat ADHD from 10 students. A dad told WSB-TV that his son said, “My medication was different. It was pink and white versus the normal color I usually take.”

In March 2020, a former school clinic aide at Clover Hill Elementary School in Chesterfield County, Va., was sentenced to five years in prison, convicted of felony child neglect, two counts of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, petty larceny and possession of a controlled substance. A Chesterfield Circuit Judge sentenced her to 18 years in prison with 13 years suspended.

Back in Fairfax County last week, the Byrnes haven’t been getting answers.

Pharmacy meetups and new ‘protocols’

In a message least week, Wallin wrote that the Fairfax County Health Department “will cover the cost for up to a two-week supply of medication for your student to ensure that your student has the medication they need to finish the school year.” She said that the agency could reimburse the costs or “we can meet you at the pharmacy to use our agency credit card to pay for the medication.”

She noted: “I am also available to vouch for the need for the additional medication if your prescribing physician or pharmacy has questions about this.”

Last week, Byrnes asked the principal and county health officials for four straightforward items: completion of the investigation, outcomes and reasoning, future processes, intentions to disseminate details and findings on the matter to the wider district and/or county.

Yesterday, parents got a sketch with a plan for more supervision in the future, but it doesn’t explain what went wrong or address all the issues Byrnes asked about.

In an email to “Parents,” Wallin wrote:

I wanted to let you know that the Fairfax County Police Department and Child Protective Services have active investigations into the diversion of medication that affected your student. We do not have any additional information about these investigations to share with you currently.

She added:

I do want to follow up and share some of the strategies that we will be integrating into our management of medications in FCPS to help prevent a similar situation in the future. We have created a new form in triplicate that parents and the School Health Aide, Public Health Nurse or designated school staff member will sign on receipt of new medication and refills. Included in this form is a two-person count of the medication received and a notation on when a refill will be needed. This form will be signed by the parent and staff member. A copy will be provided to the principal and another to the parent. The original copy will be attached to the medication log of the student and kept as part of the student’s health record. We will begin using this form during Summer School. We also will be requiring parents to bring in medication in the original bottle, ensuring that the description of the medication on the medication container is the same as the contents of the container. Additionally, next school year, for controlled substances we will be increasing the number of audits of the medication on hand to a weekly review by the Public Health Nurse. After a medication error (including documentation errors, late doses, or missed doses) is identified, the Public Health Nurse will notify parents and will develop a plan with the School Health Aide and the school administrator and check in at least weekly until process consistently meets protocol.

But back to Thursday, June 2. Byrnes asked Wallin what additional health screening the county would provide or recommend for the children impacted.

The next morning, at 7:01 a.m., Wallin replied: “We would recommend that if you have concerns you speak to your child’s doctor.”

The Byrnes had already gone to the pediatrician once, saying their daughter’s medicine didn’t seem to be working. Later that morning, the girl’s mother wrote to Wallin: “You will not wash your hands of this considering it was your employee and your department’s lack of adherence to protocols that results in my child being drugged repeatedly over the course of a school year.”

In September, Carpenter worked out a protocol with the Byrnes to get their daughter her medicine around 11:40 a.m., the health aide saying she had set an alarm on her phone to remind her to find their daughter. Carpenter also confirmed in an email that “you all can drop off up to 30 days’ supply of medication and it will remain here in a lock box, with the box being kept in a locked file cabinet.” Carpenter added: “Protocol states we must double lock controlled substances. We do weekly medication counts and log everyday when she comes to take her medication.

‘Civil rights violation’

The safety issues raised here are very serious about the failure to protect children with disabilities who are supposed to have safeguards in place under federal and state laws.

Told about this case at Greenbriar East Elementary School, Callie Oettinger, editor of SpecialEducationAction.com and parent of students in Fairfax County Public Schools, said, “This is horrifying – and it’s not surprising. Fairfax County Public Schools has a history of noncompliance with federal and/or state regulations, providing false information, and failing to meet the needs of students who have individualized education plans or 504 plans,” which are protections under Section 504 of the Americans with Disabilities Act. “FCPS leadership’s forte is egregious oversite [sic] failures instead of education,” she said.

“FCPS is being investigated by the U.S. Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights due to its actions and inactions during COVID. I hope the Office of Civil Rights will launch a county-wide investigation into FCPS’s failure to have safeguards in place that ensure children’s special needs are always addressed in full,” she added.

“Since denying access to medicine results in denying access to education, this is a civil rights violation,” she said.

‘The kiddos’

By late September, the second grader had reported to her mother that she had not taken her medicine at school. On Sept. 29, 2021, at 12:10 p.m., her mother wrote to Carpenter expressing concern. At 12:43 p.m., Carpenter wrote back, “She received today by the way. I’ve got my timer set on my cell phone. Apologies again!”

The next day, Sept. 30, 2021, though, the mom had to ask Carpenter again if her daughter got her medication. “She told me she forgot to take it again.”

Carpenter reassured her: “Yes she took it. It was a chaotic shift among the kiddos with changing classes and specials. I had to fish her out so to speak. Gonna grab her again at 11:40!”

Like many parents, the mom attempted to be good-spirited: “I trust that she’ll get it daily now, thanks for your extra effort with her, I do appreciate it!”

But Oct. 1, 2021, it was the same confusing dynamic. That day, at 11:47 a.m., Carpenter wrote, “Just gave it to her. Yes it can be hard to remember stuff at times!” That evening, at 7 p.m., the mom wrote to Carpenter, attaching a photo of her daughter: “She swears up and down that she hasn’t taken it this week! This is who you’re giving it to, right?”

Carpenter responded, “Yes!! We do name and birthday checks everyday!” She said she’d send confirmation next time with a photo.

The mom answered, again trying to avoid being “that mom” raising issues: “She swears she hasn’t been receiving it but maybe it’s just hectic.”

On Oct. 4, 2021, at 11:55 a.m., Carpenter sent the mom an email with the subject line: “Hello! 11:41AM med time!”

The lesson of this nightmare is that vigilance matters. Never apologize for asking questions and advocating for your children.

Now, the Byrnes go to school personally every day to give their daughter her medicine.

Asra Nomani is a senior contributor at The Federalist and a senior fellow at the Independent Women’s Network. This column has been republished with permission from Asra Investigates.