In announcing the creation of three new conservation easements in Henrico County, a recent press release from the Capital Region Land Conservancy made an eye-catching statement. The easements, said the Conservancy, act as a bulwark against rising pressure to develop agricultural land across Virginia “driven most recently by shifts in COVID-era lifestyles and soaring housing prices.”

This was the first time I recall anyone in Virginia making an explicit connection between the COVID epidemic, urban flight, and rising property values for agricultural land. The notion is worth exploring

The conversion of farmland into subdivisions is a long-standing concern. As the Conservancy notes, more than 339,000 acres of farmland were developed in Virginia between 2001 and 2016. In the Richmond region, more than 87,000 acres of farmland have been lost. By 2017 Henrico County had fewer than 100 farms and 10,000 acres of farmland.

The urban renaissance of the 2010s decade blunted the trend toward metropolitan sprawl. The center of gravity in development shifted back toward urban cores in Virginia and the U.S. generally. Now that momentum seems spent. Perhaps the COVID-19 epidemic is driving the reversal, but I suspect that the reality is more complex. It is also possible — consider it a hypothesis — that after a year of protests, riots and rising violent crime rates in many cities, many urban dwellers, concerned about social breakdown, fear for their personal safety. The main thing holding them back is the paucity of rural broadband and connectivity. That barrier soon may fall.

COVID-19. The Virginia Department of Health provides a breakdown of COVID-19 cases by all Virginia localities — cases, hospitalizations and fatalities per 100,000 population. While it is true that COVID-19 first mushroomed in the major metropolitan areas, the virus has since spread everywhere, and the data shows that the impact in smaller towns and rural counties is every bit as severe now as in metro areas.

Indeed, the epidemic, as measured by the number of cases per 100,000 population, is most intense in non-metro settings:

Galax — 13,607 cases per 100,000

Richmond County — 10,699

Lexington — 9,501

Buena Vista — 9,187

Greensville — 9,005

Buckingham — 8,883

Harrisonburg — 8,754

Covington — 8,223

Contrast rural Richmond County to the urban City of Richmond with 4,475 cases per 100,000. Virginia’s other major population centers are in the same range as Richmond.

Loudoun — 3,757

Norfolk — 4,087

Arlington — 4,146

Fairfax — 4,211

Chesterfield — 4,214

Henrico — 4,304

Virginia Beach — 4,380

Not every rural locality is a COVID hotbed, however. Highland County, Virginia’s least populous county, has a case rate of only 2,670 per 100,000, with zero hospitalizations and zero deaths. But the larger point remains: Few small towns and rural communities are COVID-19 havens. I do have friends who have ridden out the epidemic in vacation homes with the thought that they were safer there. Early in the epidemic, they might have been. But such a perception cannot last long in the face of reality.

Home values. Skyrocketing housing values in major metropolitan areas are a plausible explanation of why many households would want to move, if they could, to communities with a lower cost of living. House values have always been higher in metro areas than non-metro areas. But that price gap was not sufficient in the past to spark an urban-to-rural migration. Is this time different?

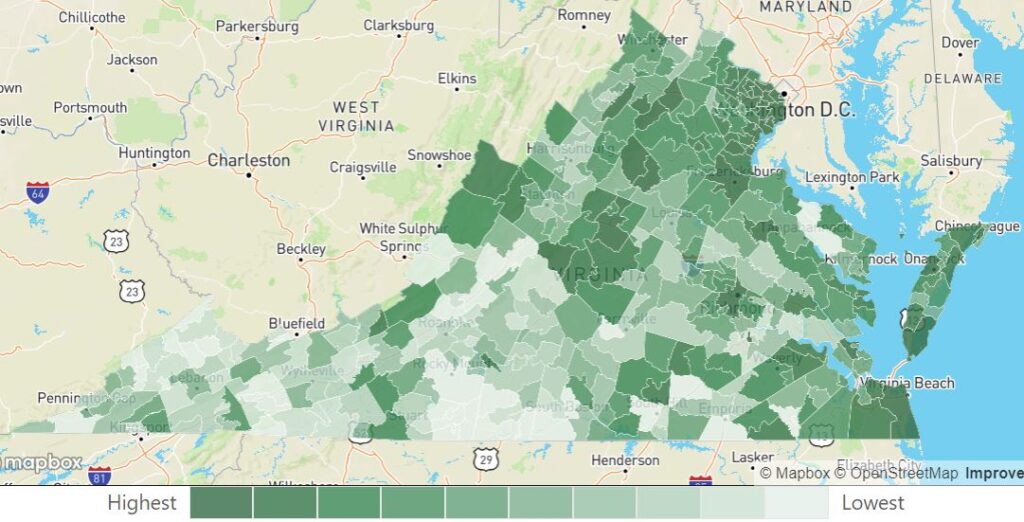

It is helpful to look at the change in housing prices, not just absolute values. This map from Neighborhood Scout shows the appreciation in the market price of homes across Virginia, broken down by what I assume is zip code.

Neighborhood Scout does not specify the percentage increases for each color range or even the time period covered, so this data can be used to support only the most impressionistic of conclusions. Housing price increases have been strong across all of Northern Virginia, the urban core of the Richmond metro, and southern Hampton Roads. But prices have surged also in select, amenity-rich rural areas such as counties bordering the Chesapeake Bay (sailing country), counties in the northern Virginia piedmont and around Charlottesville (hunt/wine country), some areas bordering West Virginia (mountain country), and even parts of Southside (red clay country??).

Housing values reflect the way people vote with their feet and pocketbooks. Higher demand leads to higher prices. As this map shows, there is a lot of variability in “rural” Virginia. If we use the change in housing prices as an indicator, we can see that amenity-rich localities are experiencing an increase in demand. People are buying weekend/vacation homes. Some are riding out the epidemic in those homes. But will they stay or will they return when the epidemic subsides?

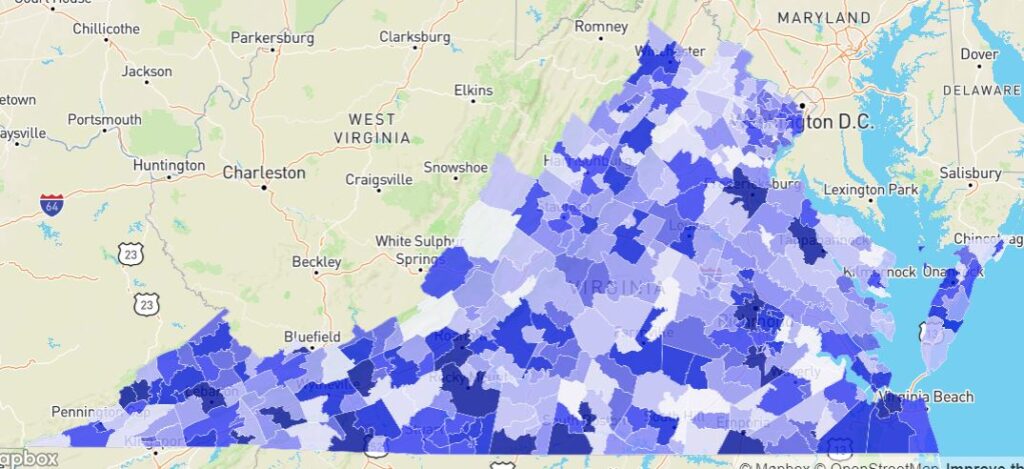

The crime hypothesis. People share a stereotype of rural America as bucolic communities where people look after one another, residents can still leave their doors unlocked, and crime rates are low. The stereotype is accurate in some places, less accurate in others. Here’s the Neighborhood Scout map for relative crime rates, showing gradations between “safest” (light blue) and “most dangerous” (dark blue).

Yes, urban zip codes tend to be among the most dangerous, especially inner-city zip codes. Even some suburban localities — Henrico, Chesapeake, Chesterfield, Suffolk — aren’t so safe. But many non-metro areas are far from havens of tranquility. Look at Southwest Virginia, the Shenandoah Valley and Southside where deindustrialization and the opioid epidemic have ravaged communities.

On the other hand, the very safest zip codes from a crime perspective are almost all rural. And there appears to be considerable overlap between the safe zip codes and the high-amenity zip codes where housing prices are increasing. If a meaningful number of people is moving to safe, high-amenity rural areas, it is not unreasonable to postulate that safety is one of their motives.

I would conjecture that most of these people are retirees or owners of weekend/vacation homes. Advancing age makes people feel more physically vulnerable and risk averse. So far the migrants have not tended to be working-age people tethered by their jobs to the major metropolitan employment centers. Major constraints have been a reluctance by major employers to encourage work at home, and a lack of competitive rural broadband service even when telecommuting was an option.

Rural broadband. The COVID-19 epidemic has taught us that many of us can work effectively from home. The impact, however, has been limited mainly to metropolitan areas which have large concentrations of knowledge workers. The spotty nature of rural broadband has worked against a large-scale movement of working-age Virginians to rural areas.

Enter Elon Musk. The American with the nation’s second biggest ego (following you-know-who) is rolling out a low-earth-orbit satellite communications network, Starlink, capable of beaming broadband service into remote areas. Musk is notorious for his hype, so most people have taken his grandiose claims with a grain of salt. However, early reviews are highly positive. From the ZeroHedge blog:

Photos are starting to leak from SpaceX Starlink beta users, who are trying the satellite broadband service in remote areas for the first time. … One beta tester shared his experience on Reddit after he brought his Starlink equipment to a remote forest in Idaho. There, he said he was able to achieve 120Mbps download speeds and access the Internet at lightning-fast speed.

He wrote that the service “works beautifully.” He continued: “I did a real-time video call and some tests. My power supply is max 300w, and the drain for the whole system while active was around 116w.”

At his house, he said he got 135Mbps download speeds when the dish was at a ground-level spot with “limited obstruction.”

Over at Dollarcollapse.com, John Rubino explores the implications:

A pandemic causes your mayor to panic and lock down the city. There go the park, friends, and restaurants. And before the horror of this new normal has a chance to sink in, civil unrest explodes and turns your once-iconic neighborhood into a Mad Maxian war zone of burned-out cars and boarded up storefronts.

If it was just you, you might stick it out. But with a family, this life is now untenable. So you look into moving, preferably to somewhere semi-rural where neither a lockdown nor riots will ever be a problem and the kids can actually play outside. Maybe it’s time to indulge your fantasy of working remotely from a homestead in a gorgeous place.

But you immediately hit a technological speed bump: Broadband Internet, which up to this point had seemed both ubiquitous and a basic human right, isn’t available on the homesteads you now covet. The only option out there is low-tech, unreliable, molasses-slow satellite Internet that, if the reviews are to be believed, is worse than nothing at all.

StarLink isn’t as fast as urban gigabit fiber connection, says Rubino, “but it’s more than adequate for Zoom calls, shared coding projects and the like.” Rubino foresees fraying cities like New York and San Francisco emptying out, lurching towards bankruptcy and becoming even more unlivable. I’m not sure any Virginia cities are likely candidates for such dystopian scenarios, but their fiscal condition is worth watching.

The COVID-19 epidemic will subside eventually, and the lockdowns will be rolled back. But broadband is here to stay. And I’ll bet that civil unrest is, too. Those trends portend well for Virginia’s amenity-rich rural counties.