People who are out of work and/or facing financial difficulties are significantly more likely to suffer depression than others, according to data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey for August 19-31. That’s hardly a breath-taking conclusion. But thanks to the survey, we have extensive data on the extent to which economic insecurity is impacting mental health during the COVID shutdown.

In Virginia, according to the survey data, young adults are more likely than their elders to feel “have little interest or pleasure in doing things” nearly every day — 9.4% of Virginia 18-to-29-year-olds compared to 0.6% in the 70-to-79 age bracket.

There was little difference in responses between males and females, or between households with and without children. While there were differences between racial/ethnic groups, the variability was relatively narrow and largely explainable by socioeconomic status. (Asians were the main outlier; they were twice as likely to report being depressed as whites and blacks.)

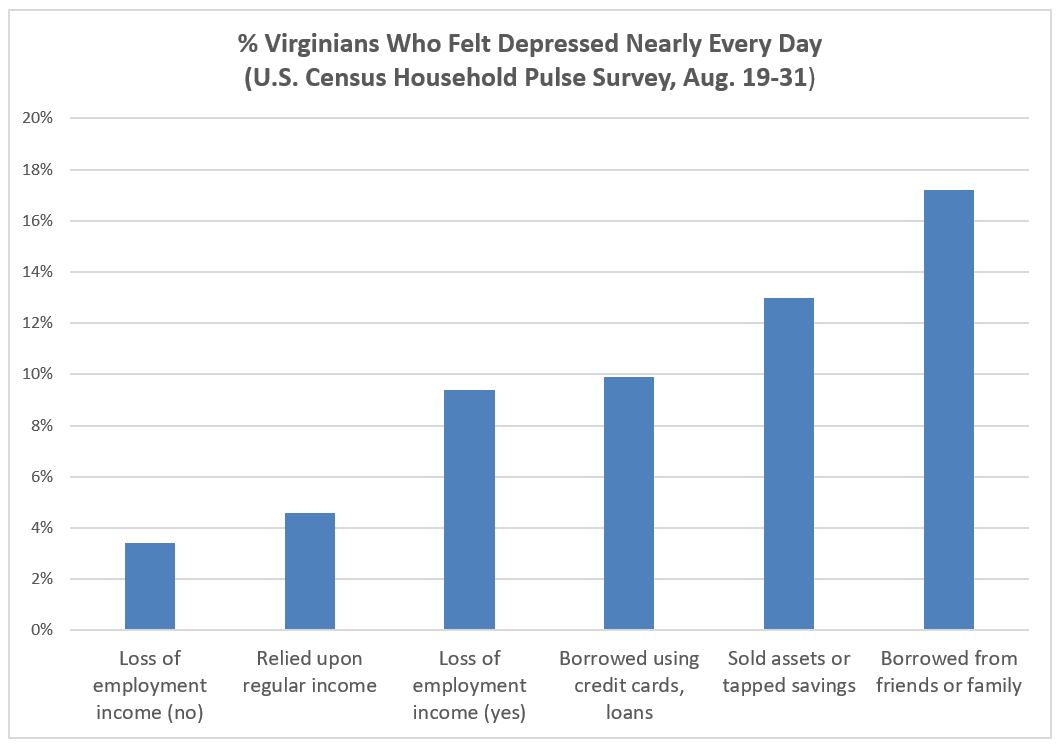

Conversely, households that had a member experiencing a loss of employment income were almost three times as likely to experience depression — 9.4% versus 3.4% for those who hadn’t lost employment income. Supporting the tie-in between income and depression was the fact that households in lower-income brackets were significantly more likely than more affluent Virginians to report symptoms of depression.

Another finding of significance is that 11.8% of the “never married” category responded that they felt depressed nearly every day, almost three times the rate for divorced/separated (4.2%) or married (3.9%) Virginians.

The survey queried Americans about different things they did to meet their spending needs in the previous seven days. Among those who had borrowed money from family and friends, 17.2% felt depressed nearly every day, as were 13% of those who had sold assets or drained savings, and 9.9% of those who had used credit cards or taken loans.

The Census Bureau notes that the data are “experimental” and that users should use caution when drawing conclusions. Sample sizes may be small and the standard errors may be large.

Bacon’s bottom line: Even acknowledging the limitations of the data, the numbers tell a consistent story. Economically vulnerable segments of society — young adults, lower-income households, families with only one bread-winner, people who had lost jobs and were forced to borrow money — are more likely than the general population to be stressed out and depressed.

The data drive home the mental-health costs of the economic devastation wrought by the COVID-19 shutdown. When we examine the costs, benefits and risks of emergency measures to stem the spread of the coronavirus, we must consider the effects not only of lost jobs and lost income but the downstream effects on anxiety, depression, and mental health…. which in turn have their own downstream effects on physical health.