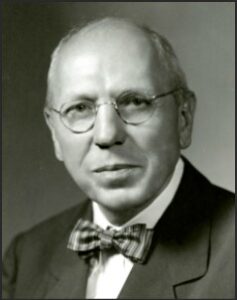

by Phil Leigh

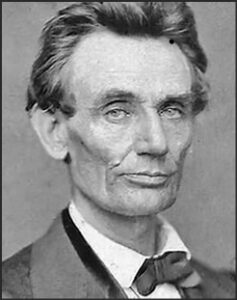

Based upon a background report on Douglas Southall Freeman (1886-1953) by Dr. Lauranett L. Lee, the University of Richmond removed his name from Mitchell-Freeman Hall owing to his alleged racism. All the good that he had done for the school’s funding and academic reputation as a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, Board of Trustees Member and Rector counted for nothing. Even though the midpoint of his adult career was 1930, the university administrators are holding him to today’s racial standards without any allowance for being part of a different era when his racial attitudes were judged moderate and often sympathetic to blacks. Despite their similarity to those of Abraham Lincoln, the University of Richmond demonizes Freeman for his racial beliefs while its leading historian and former president, Edward Ayers, glorifies Lincoln.

In contrast, the university administrators extend Freeman’s critics special allowances concerning time, place, and race. They fault Freeman for opposing interracial marriage, even though 75% of whites and 73% of blacks opposed it in 1968, fifteen years after Freeman’s death. Additionally, when Freeman referred to blacks in his writing he normally did so with the then-respectful term “Negro” as opposed to “colored” or the unmentionable “N-word.”

In contrast, Dr. Lee, who is black, constantly capitalizes the “B” in Black when referring to African Americans (83 times) in her 100-page criticism of Freeman while always using a lower case “w” when referencing white people. Although I’ve contacted professors Lee and Ayers as well as president Crutcher, nobody at the University of Richmond has replied. Consequently, it’s most logical to assume that her use of upper-case “B” in black and lower-case “w” in white is an expression of endemic black superiority endorsed by the university.

Let us now consider the comparative racial attitudes of Lincoln and Freeman. Both believed in racial segregation, although Freeman argued that the separate black public facilities should be the equal to those of whites. In the second year of the Civil War President Lincoln met with five black leaders at the White House:

“You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both . . . If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated.”

The President then recommended that the blacks leave the United States to colonize other countries such as Colombia (Panama) or Liberia.

“. . . It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated. I know that there are free men among you . . . not . . . much inclined to go out of the country . . . I suppose one of the principal difficulties in the way of colonization is that the free colored man cannot see that his comfort would be advanced by it. . . . This is (I speak in no unkind sense) an extremely selfish view of the case.”

Eight years earlier, and seven years before the Civil War, Lincoln explained that he did not want slavery in the western territories because he did not want blacks there, neither slave nor free: “The whole nation is interested that the best use shall be made of these territories. We want them for the homes of free white people.”

Despite his untimely death, Lincoln successfully retained the western territories for free white people. Of all twenty-two states admitted to the Union after Texas in 1845 down to the present day, nearly 180 years later, all but two joined the USA when blacks composed one percent or less of their populations. The two exceptions are the border states of Oklahoma and West Virginia, the latter admitted as a slave state when Lincoln was still President.

Lincoln, of course, is most remembered for his Emancipation Proclamation, which was announced in September 1862 and implemented in January 1863. It prohibited all Americans from owning slaves, except for those who happened to reside in the United States. Lincoln admitted it was adopted as a war measure to weaken the Confederacy. He was aware that it might even ignite a servile insurrection in the South that would cause the Confederate soldier to abandon his army so that he may return home to protect his family from massacre. A few weeks before he released the Proclamation, Lincoln was so discouraged by the progress of the war that Attorney General Bates recorded the President as saying “he was almost ready to hang himself.”

While Lincoln’s militarily motivated Emancipation Proclamation was an enlightened initiative for his time, Freeman was similarly outspoken ahead of his time and place for racial equality under the law and equality of separate public facilities. Even professor Lee admits that between 1936 and 1942 Freeman urged his newspaper readers to provide more funding for black schools. She also admits that his editorials “on lynching, judicial equality, and police violence, would at times earn praise from the Black community.”

This column is republished with permission from the Civil War Chat blog.