It’s sad to see that my friends at the Partners for College Affordability & Public Trust (once a sponsor of Bacon’s Rebellion) have embraced the “social justice” paradigm for higher education. I whole-heartedly endorsed their mission when it focused on containing the rising cost of college attendance generally and advocated increased transparency for higher-ed governance. But in a new paper, “Fair Funding and the Future of Higher Education in Virginia,” the Partners have succumbed to the mantra that higher ed should be not only affordable but “equitable” and “transformative.”

The paper, which is co-written by Education Reform Now, advances a series of premises: (1) that “a state of de facto segregation by income and race exists in Virginia higher education;” (2) that higher education should promote “social mobility” for lower-income Virginians; and (3) that colleges and universities should strive to advance social mobility by closing the racial admissions gap.

In this schema, it not the job of Virginia’s higher-ed system as a whole to provide social mobility for lower-income Virginians. Virginia needs to revamp its public support for higher-ed to “erase equity gaps” at each institution, the study report says. “At some of Virginia’s most prestigious public institutions, barely 1 out of ten undergraduates come from low-income households and only a quarter come from low- and middle-income households combined.”

What this analysis ignores is that higher-ed is largely powerless to address the equity gap, which arises from socioeconomic conditions and the failures of Virginia’s K-12 school system. Virginia’s elite institutions cannot boost their numbers of lower-income students significantly without either sacrificing the rigor of education or exposing them to the risk of failure, dropping out, and going deeply into debt.

Virginia’s higher-ed system was set up to serve students across a wide spectrum of academic preparedness — from two-year community colleges, to smaller liberal arts colleges, to research universities, to nationally elite institutions such as the University of Virginia, Virginia Tech, and the College of William and Mary. The system provided an appropriate entry point for students of varying academic ability.

Unfortunately, higher-ed’s paroxysm of angst over equity has obliterated the rationale for Virginia’s system. Today, every college and university has established a goal of increasing its minority representation (unless the minority happens to be Asians, who are supposedly “over-represented”) — even as Virginia’s private universities and competing out-of-state universities are doing the same thing; even as the state funnels money into Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HCBUs) serving the lower-income African-American population; and even as the catastrophic failure of of the K-12 public school system throttles the supply of college-ready minority students.

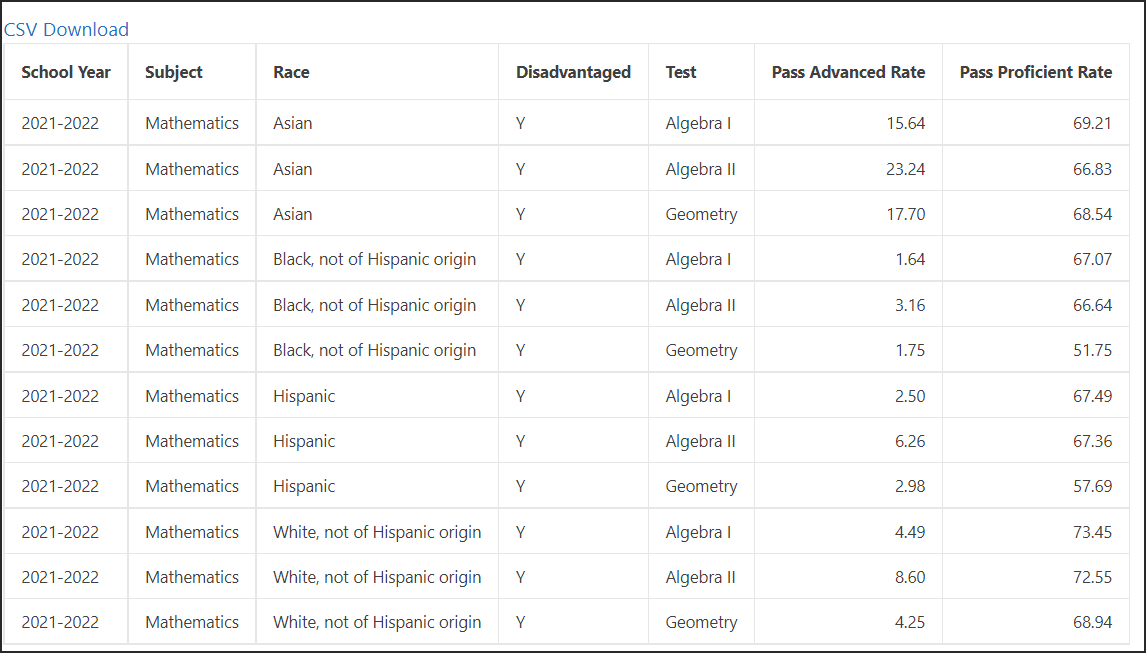

This chart pulled from the Virginia Department of Education Build-a-Table shows the pass rates for Algebra I, Geometry, and Algebra II statewide in the 2021-22 school year, broken down by major racial/ethnic category for economically disadvantaged students.

As can be seen here, a respectably high percentage of disadvantaged Asian students achieve “advanced” pass scores for their math SOLs. By contrast, only a tiny percentage of disadvantaged Whites and Hispanics do, and a miniscule percentage of disadvantaged Blacks do.

To what degree does scoring “advanced” on Virginia’s math SOLs predict success in college-level work?

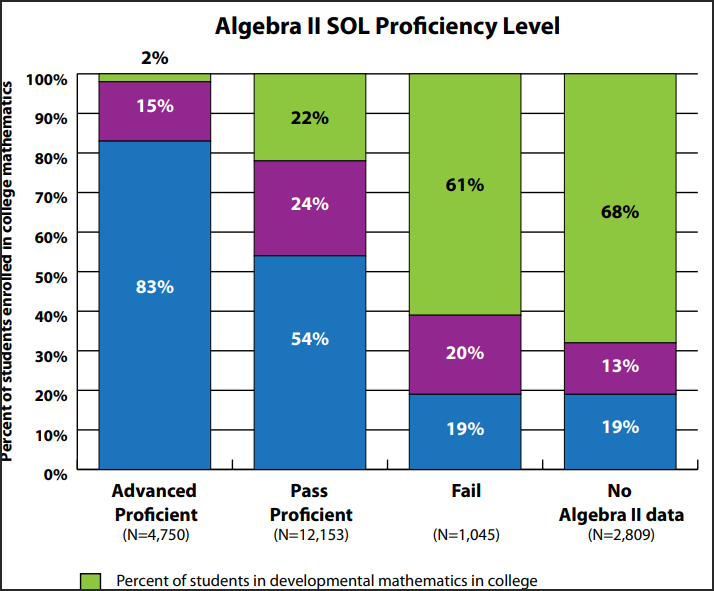

In 2012 VDOE conducted a study based on Virginia high school graduates who entered two- and four-year higher education institutions in Virginia in 2008 and 2009. The database (which masked personal identities) encompassed more than 31,000 students. Among the questions lawmakers wanted answered was: to what degree did passing SOL tests predict superior college outcomes? (The comparison between then and today is not perfect because the “cut” scores for SOL tests have been changed, but it’s useful as a rough guide.)

The blue blocks show the percentage of students in each of four SOL categories — advanced, passed, failed, no data — who went on to college, enrolled in math courses there, and managed to earn a C or better. Eighty-three percent of students who scored “advanced” on their Algebra II SOLs and later took college math courses passed them, compared to only 54% who had passed their SOL at the basic level, and 19% who had failed.

There are important lessons here. SOLs are not destiny. It is possible to fail the Algebra II SOL and still pass college-level math classes. However, scoring “advanced” in the SOL does indicate a significantly higher probability of passing college-level math and “failing” indicates a significantly lower probability of performing college-level work.

The disparity is actually more lopsided than indicated in the study, which does not distinguish between community-college courses, four-year college courses, or courses at elite universities in engineering, physics and other STEM disciplines where math competency is critical.

Now, circling back to the problem faced by UVa, Tech and W&M (not to mention STEM programs at George Mason, Old Dominion, Virginia Commonwealth and other universities)…. Only a small percentage of economically disadvantaged Virginia youth have the academic chops to succeed in elite math-intensive disciplines.

Yes, something needs to be done to create opportunity for all. But that “something” is in the K-12 public education system. The idea of criticizing UVa and W&M for recruiting relatively small percentages of low-income and minority students (and graduating them at a high rate) is horribly misplaced. The top-performing two or three percent of disadvantaged Virginia minorities get vacuumed up by the Ivies and other super-elite institutions, leaving the elite Virginia publics raiding students who would prosper in a university with a lower prestige ranking, and so on down the line.

At least the Partners study recognizes this risk, stating, “Merely enrolling more students of color, students from rural communities, and adult learners without those students earning a credential not only fails to increase the return on investment in higher education; it can actually turn it negative by saddling a student with debt but no degree.”

But that’s exactly what’s happening. Thousands of lower-income students are being lured into a higher-ed system for which they are academically unprepared, dropping out, and accumulating large debts in the process — making them worse off than before — even when they could have pursued manual or technical trades that pay exceedingly well in today’s job market. Insisting that “equity” requires elite institutions to inflate the numbers of low-income students beyond current levels would be profoundly damaging — not only to the institutions but to the students.