by James A. Bacon

The school districts of Southwest Virginia are among the poorest in the Commonwealth, but that hasn’t stopped them from out-performing more affluent districts across the state. Public schools in Region VII, stretching from the City of Radford to Virginia’s far-western tip in Lee County, have the lowest per-pupil funding in the state, yet they have the highest average pass rates for Standards of Learning (SOL) test scores. I highlighted those findings in a recent post. What I couldn’t say then was how Region VII managed to score the best results of the state’s eight education regions.

So I talked to Matt Hurt, curriculum director for the Comprehensive Instructional Program (CIP), a bottom-up initiative starting in Southwest Virginia, to find out more. It is a remarkable story and an encouraging one. With the right approach, Virginia schools can lift themselves up by their boot straps. Lesson for the General Assembly: The answer isn’t Mo’ Money.

Southwest Virginia students have not always been top SOL performers. Their rise to the top has occurred in just the past few years, says Hurt. The secret: Local school districts pooled resources to do three main things: (1) identify the most successful teachers across the region; (2) share their instructional materials and other best practices; (3) set high expectations, and (4) measure what works. Five years have made a significant difference.

Despite a higher percentage of disabled and economically disadvantaged students, 82.8% of Region VII students passed their math SOLs compared to 77% for the state, and 81.2% passed their reading SOLs compared to 77.2% for the state. While pass rates declined this year statewide, they increased slightly in Southwest Virginia,

The CIP initiative arose from an informal collaboration of Southwest Virginia school superintendents who met regularly to discuss common problems. In the 2013-14 year, the bottom dropped out of SOL pass rates after the state had instituted new, tougher standards, and Southwest Virginia had been no exception. Meanwhile, the General Assembly had been slashing state support for K-12 education, and the SW Virginia superintendents didn’t see any help coming from Richmond. They decided to pool resources and share best practices, and they hired Hurt to drive the Comprehensive Instructional Program forward.

Not all school systems were big enough to support their own statistician. Hurt gathered the data and formatted it so member districts could see how they were performing — and how they were performing compared to their peers. “The data gave them a frame of reference,” he says. He also used the data to figure out which teachers had students with the highest SOL pass rates (after adjusting for the percentage of disabled and economically disadvantaged kids). Then, says Hurt in an offhand reference to collecting their instructional materials, “We spent the 2014-15 school year stealing their stuff.”

In 2015-16, the first year of implementation, CIP put those materials on the web, and made them freely available to other teachers. CIP also organized events where teachers could share best practices. “We put teachers in the drivers’ seat,” says Hurt. “We bring the teachers together once a year. They plan the specific skills they will teach quarter by quarter.”

“When the teachers first got together,” he says, “they complained that the initial benchmarks were too hard. Now they’re saying they’re too easy. Expectations are increasing. As expectations go up, so to the scores.” Many kids tend to skate by with the least amount of work they can get away with, he explains. If teachers raise expectations, students have to perform at a higher level.

In the few years it has been operating, says Hurt, CIP has learned an important lesson: It is important to set priorities. “We can do one thing well or a lot of things poorly.” The thing that CIP and its member school districts want to do well is equip as many students as possible with the core skills they need to pass the SOLs, which also are skills they need to function in society. “You’ve got a lot of school board members who run for office because they have an ax to grind or a pet project. A lot of times, those pet projects are not designed for disadvantaged kids.” CIP encourages school districts to strip away projects that don’t contribute to the essential goal of teaching core skills.

A second lesson learned: “The amount of money that’s spent on education,” says Hurt, “doesn’t move the needle that much when it comes to SOLs.” Indeed, in some years, more money correlated slightly negatively with performance.

Hurt defends the SOLs against those who criticize them for encouraging teachers to “teach to the test.” His response: “Which of the skills do you not want your kids to master?” The history test, he acknowledges, “is nothing more than a game of Trivial Pursuit — can you regurgitate these facts?” But he insists that reading, writing, and math are fundamental skills. “If you want to lift students out of poverty, that’s what you’ve got to focus on.”

The philosophy may not work so well for the children of doctors and lawyers, Hurt concedes. The school systems are poor, so they can’t afford as many specialty classes that advanced students might want to take. “The higher-performing kids might be losing out,” Hurt concedes. His daughter attends school in Wise County, one of the poorest districts in the state. There is no money for robotics or coding. “There are very limited opportunities for her to do anything advanced.”

A third lesson learned: Set high expectations. “If a kid doesn’t do what a teacher expects him to do today — if he doesn’t grasp the skill — the teacher will keep him in the classroom during recess or the exploratory class so they can work with that kid.”

A fourth lesson: Relationships are critical. “A lot of at-risk kids come from families where the parent’s job is walking down to the mailbox and picking up a check.” Such parents have low expectations, they’re not concerned with grades, and their kids tend to be unmotivated. But a teacher who bonds with these student can provide that motivation.

It takes more than teachers, Hurt though says. School principals, support staff, even the central administration all need to be involved. He says he is coming to the conclusion that having “home-town folks” as teachers and principals is important. People who want to build their careers and lives close to home are more invested in the community than transients who treat their jobs as stepping stones. Educators with a home-grown orientation are more likely to invest in relationships with students, he theorizes.

The Virginia Department of Education has been helpful to the CIP initiative, especially with technical things like collecting statistics and putting on webinars. But otherwise VDOE has played little role in CIP. “From my perspective, [the Department of Education] is a body that responds to the legislature.”

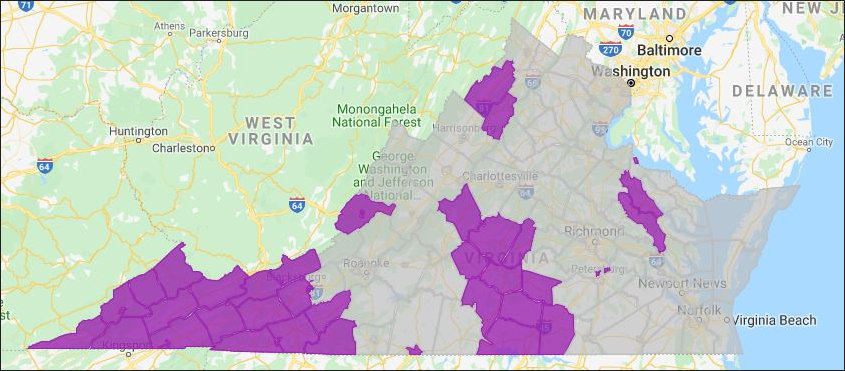

Despite the lack of state support — or perhaps because of it — CIP is catching on among rural school districts. The Wise-based consortium, which had 21 school divisions in 2015-16, now is up to 41 divisions, including some from Southside, the Shenandoah Valley, and the Chesapeake Bay area.

Bacon’s bottom line: Perhaps the most important lesson of all is that change doesn’t have to come from Richmond. Indeed, bottom-up change based on a pragmatic philosophy based on keen understanding of local conditions is more likely to be effective than top-down change imposed by political ideologues in the state capital. While the Northam administration waters down SOLs in pursuit of social and racial “equity” with calamitous results so far (as measured by SOL scores), it is encouraging to see that a number of school districts have chosen a different path. The supreme irony is that SW Virginia educators are succeeding in narrowing the gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students, while the state as a whole is not.