It turns out that blacks and Hispanics are not the only population sub-groups in Virginia who are resisting the idea of getting vaccinated against COVID-19. So are rural, non-college-educated whites in Appalachia, reports the Roanoke Times.

Hesitancy has dropped among blacks and Hispanics, but concerns among rural whites have increased that the vaccine was rushed to market and has widespread side effects. The problem has gotten so pronounced that a team of Virginia Tech researchers is working to determine if social media-driven misinformation fuels the resistance.

The Northam administration moved aggressively to address vaccine hesitancy among blacks and Hispanics by hiring marketing firms to push the pro-vaccine message in minority communities and setting up mobile and pop-up clinics in minority communities were vaccination rates were low. In Danville, the administration went so far as to ban out-of-towners from utilizing a pop-up clinic that was meant to serve local minorities even though it was administering only a fraction of the number of vaccines it had the capacity for.

So far, Southwest Virginia has seen no comparable demographically targeted initiatives from the Virginia Department of Health.

A Virginia Tech survey of residents of the Roanoke and New River Valleys (the least rural areas of Southwest Virginia) found that 27% of respondents were extremely unlikely to get vaccinated while another 42% were on the fence. Only 18% expressed confidence in the opinions of Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who is highly esteemed and widely quoted in mainstream media. Survey respondents do place a high degree of trust in their primary care physician. Trouble is, many people in the far Southwest don’t have doctors.

Karen Shelton, who directs public health for the state west of the New River Valley, tells the Roanoke Times that the United Way of Southwest Virginia is working on a marketing campaign that will use “community influencers” to get out the word about the value of vaccination. Meanwhile, Emory and Henry College in Washington County is trying to dispel myths among its students.

There is no indication in the article that the state has initiated any outreach to poor rural whites of Appalachia comparable to what it has done for blacks and Hispanics. At least Northam’s vaccination czar, Danny Avula, appears to be aware that a problem exists.

“I do think there’s a whole another element of engagement around vaccine hesitancy that is targeting more rural and conservative communities and that we didn’t we didn’t readily prepare for that,” he tells the Roanoke Times. “I don’t know that we anticipated that’s where the resistance was.”

One might legitimately inquire why Team Northam is so behind the curve in addressing the problem in Appalachia compared to the alacrity with which it dealt with lagging vaccinations in minority precincts.

I would hypothesize a two-fold explanation. First, minority populations are served by advocacy groups and politicians who are accustomed to extracting benefits from government on the basis of racial and ethnic identity, while such groups do not exist in Appalachia. Second, the Northam administration, which pushes the systemic-racism narrative, is highly sensitive and responsive to the demands of minority groups. It probably does not help that rural Appalachian counties are overwhelmingly conservative and Republican.

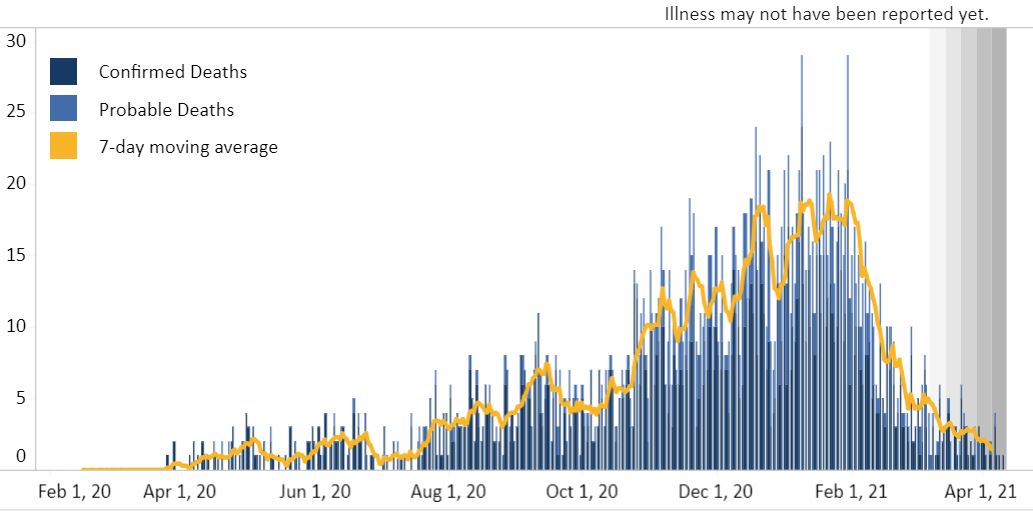

Despite local resistance to vaccinations, the number of confirmed cases, hospitalizations and deaths in the Virginia Department of Health’s “Southwest” region is markedly lower than it was two months ago, as it is across the state.