by James A. Bacon

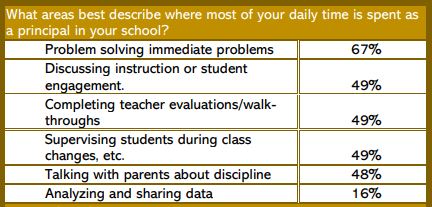

Most principals of Virginia public schools — 70% — are “generally satisfied” with their jobs, although half work 60 or more hours and two-thirds feel like they spend most of their time solving immediate problems rather than creating great schools. Those are some of the findings of a survey of 467 public school principals by the Virginia Foundation for Educational leadership.

However, one in seven (14%) responded that “the stress and disappointments involved in being a principal at this school aren’t really worth it,” and one out of four (26%) said they did not have as much enthusiasm for the job as when they began. Remarkably, one in ten (11%) answered, “I think about staying home from school because I’m just too tired to go.”

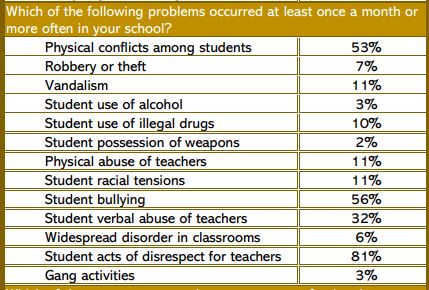

A significant issue for many principals is school discipline. Four out of five (81%) reported the necessity of dealing with student acts of disrespect for teachers at least once a month, and more than half (53%) deal with physical conflicts among students at least monthly. Large percentages also reported student bullying and verbal abuse of teachers.

However, only six percent said their schools had experienced “widespread disorder in classrooms.”

The purpose of the study, “Virginia Principal Retention, Attrition and Mobility Study,” was to gain insight into “why excessive turnover exists and the relationship between principal turnover and various features of the principalship; which principals are most likely to leave; and which schools are more vulnerable to principal turnover.”

The study highlighted several influences on principal burnout and turnover. Twenty-three percent of principles were concerned by high turnover in central office staff in their division, and 28% said there is not enough central office staff to support them in their role. Likewise, 41% of high school principals, 49% of middle school principals and 57% of elementary principals stated they do not have adequate student services personnel at their school — a finding the study authors found “significant.”

While there has been some movement to increase the number of counselors and support personnel, the evidence continues to demonstrate that our young people are challenged in many different ways. Trauma-informed care, mental health support, conflict resolution, and direct and virtual bullying intervention are areas in which students consistently need help. Requiring teachers and principals to take a course or complete a module cannot sufficiently prepare them to deal with students who are facing these types of serious issues. Students in crisis need trained personnel.

The report also found that roughly a third of principals say their administrative teams are inadequate to support faculty and staff. “A deeper analysis,” the study suggested, “could reveal the need for higher ratios of assistant principals per school [and] additional counselors, social workers, and school psychologists.”

Bacon’s bottom line: The study generated considerable useful information, although it strikes me that follow-up analysis could provide even more insight. For instance, the study did not correlate the principals’ responses with different categories of schools, either by the size of the school; urban, rural, suburban classification of the school district; racial or socioeconomic composition of the school; or level of spending either in the school or district. Likewise, the study provided no sense of whether the principals’ perceptions have changed over time. Is morale getting better or worse? Are the staffing or disciplinary problems easing or intensifying?

I hypothesize that there is a meaningful correlation between principal morale, turnover and retention on the one hand and the composition of the student body on the other; schools with higher percentages of low-income “disadvantaged” students, blacks and Hispanics, and students with disabilities suffer more disruption requiring principals to spend more of their time dealing with disciplinary issues.

It appears that schools suffer from a severe case of mission creep. Once upon a time, the mission of schools was to instruct students in English, math, science, and history. There was a clear focus. Students who didn’t get with the program were expelled from class, suspended, or even referred to law enforcement. Teachers spent more time teaching. Now schools have become vehicles for social justice. Not only do teachers teach the willing, in the quest for equal outcomes between ethnic/racial groups they are required to teach the unwilling. Schools are expected to remedy behavioral issues arising from dysfunctional families and neighborhood environments.

Principals and teachers have spent their careers learning how to teach, not solve broader societal issues stemming from poverty, familial breakdown and social injustice. It is a testament to their dedication that burnout and turnover isn’t worse.