As faithful readers know well, I remain unpersuaded that the world is facing global-warming Armageddon or that we need to force a restructuring of the global energy economy to avert it. But as long as there’s even a remote chance that the emission of greenhouse gases (primarily CO2) might be driving cataclysmic climate change, I suppose, it’s good to see CO2 emissions heading down.

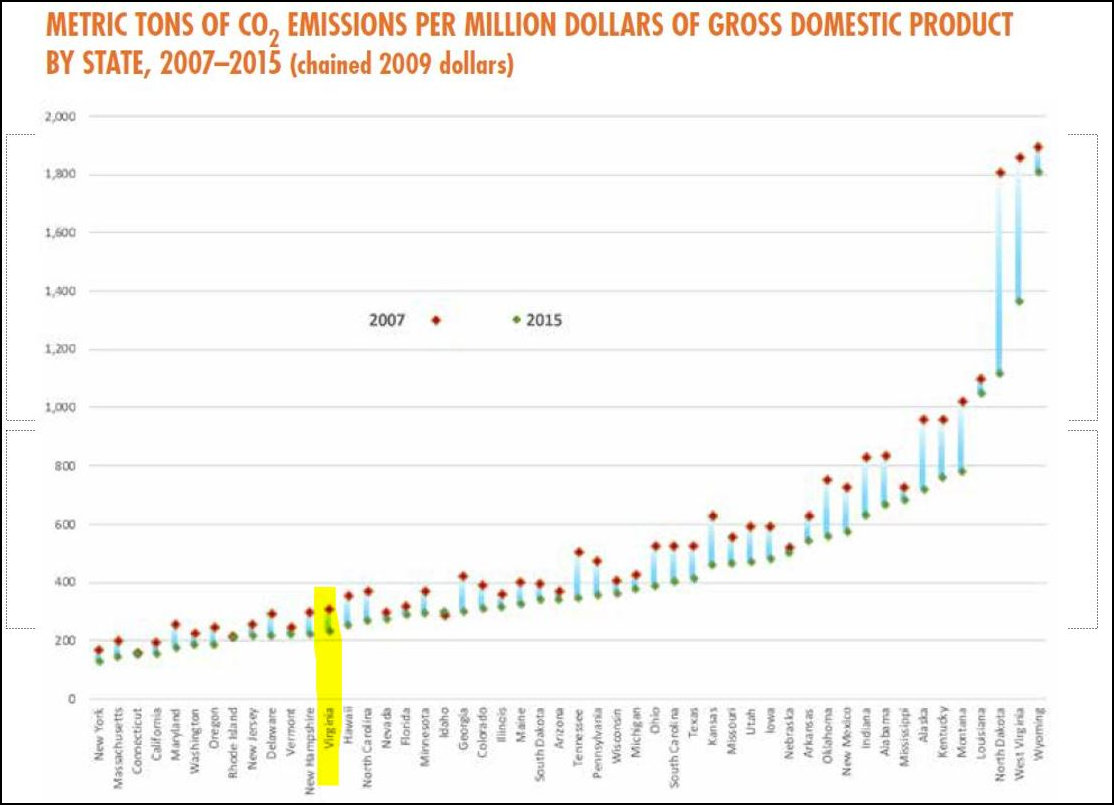

Unlike some holier-than-thou nations I could name, the United States actually is making progress in reducing its CO2 emissions. And Virginia looks pretty good by comparison to other states, which suggests that Virginia is looking pretty good by global standards. Arguably, the most useful measure of carbon intensity is the number of metric tons of CO2 emitted per million dollars of Gross Domestic Product. The lower the number, the more carbon-efficient the economy. As can be seen in the chart above, Virginia is the 13th most carbon-efficient state in the country. Somehow, despite all the caterwauling, we must be doing something right.

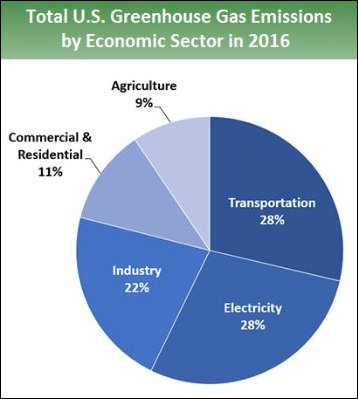

The debate over Virginia’s energy policy over the past few years has focused almost entirely upon the electric power sector. But electricity accounts for only 28% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. An equal proportion comes from the transportation sector, which receives scant attention in the Old Dominion these days. Major contributions come also from industry, commercial & residential, and agriculture, which also goes largely ignored.

Market forces are driving the push to renewable energy in the electricity sector, and we would be seeing more solar power regardless of what the activists and politicians were doing. The reason: Solar’s time has come. Solar is an economically competitive power source, and an increasing number of major corporations are demanding it. As a consequence, Virginia’s largest electric utility, Dominion Energy Virginia, has done a remarkable about-face over the past two years, as can be seen by comparing the narratives of successive Integrated Resource Plans. As Dominion plots its energy future, it foresees a continued shift away from CO2-intensive coal to zero-carbon solar, using natural gas combustion-turbine engines to counter the inevitable variability in solar production.

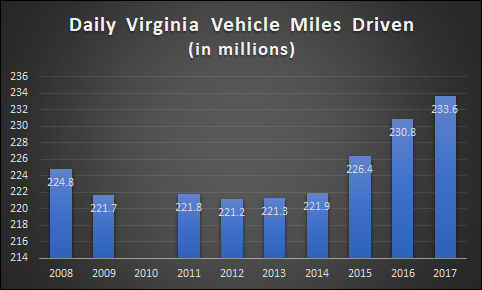

By contrast, public policy is central to shaping the carbon intensity of the transportation sector — not by setting miles-per-gallon standards for vehicles as much as by shaping land use patterns that determine how frequently people drive their cars and how far they drive. Once upon a time, Virginia environmental groups kept these issues in the spotlight. For whatever reason, they have faded from view. But look what’s going on:

This graph, based on Virginia Department of Transportation data, shows how the average daily vehicle miles traveled dipped after the 2008 recession, leveled off for five years, and then began climbing again in recent years. (2010 numbers were not available from the data source I consulted.) Increased VMT translates directly into increased CO2 emissions. Curiously, the recent increase seems not to have set off any alarm bells. Needless to say, staff-shriveled Virginia news outlets aren’t writing about it. Even environmental groups, absorbed by the dramas of Mountain Valley Pipeline and Atlantic Coast Pipeline construction, seem to be ignoring it.

One long-term solution to rising VMT is building more Walkable Urbanism — compact, pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use development — that enables people to conduct their daily business with fewer and shorter car trips. Another long-term solution is figuring how out to harness the fast-approaching transportation revolutions of self-driving cars and Transportation as a Service. Public policy discussions are occurring behind the scenes — I understand that the Northam administration wants to make its mark in transportation policy by emphasizing innovation — but so far the rubber has yet to meet the road.

Then there’s the other 44% of CO2 emissions from the manufacturing, agriculture, commercial and residential sectors. I have seen next-to-zero attention paid to these economic sectors. One way to reduce the carbon intensity of Virginia’s economy would be to encourage the conversion of grassland and cropland to forest, thus sequestering carbon in trees — the reverse of the clear-cutting of Amazonian rain forest. This is happening on its own, without state government prodding. Perhaps it’s best to leave a good thing alone. But I’m surprised that we’re not hearing more about ways to accelerate the process.

There is tremendous potential, too, in building automation to conserve energy for heating, cooling, and lighting. While individual property owners are investing in energy efficiency, the next frontier is in collaborative projects across office parks and downtown business districts. Virginia state and local government have been totally AWOL.

In sum, If Virginia is one of the more carbon-efficient states in the U.S., it is hard to give any credit to the political class. The General Assembly has ratified a large-scale commitment to solar energy and grid modernization that likely would have occurred if left to normal market and regulatory processes. Meanwhile, nothing substantive is being done about CO2 emissions in transportation, manufacturing and the built environment. Perhaps that’s just as well. All things considered, Virginia is doing just fine. There’s a good chance that the politicians would just screw it up.