By Steve Haner

Having received and mostly spent $3.1 billion in federal COVID-19 “relief” funding already, Virginia’s state and local governments now will have another $2.7 billion in the fourth and latest (but likely not last) federal spending bill tied to the ongoing pandemic and unemployment crisis.

The word relief is in apostrophes because Virginia’s state budget, as previously reported, is surprisingly strong in this time of economic stress, strong enough to pour dollars back into the state’s reserve funds Other states are in much worse shape. But just as with the individual COVID payments, need is not a factor. The idea is to stimulate personal – and government – spending across the board.

Much of this new $2.7 billion will pay for things Governor Ralph Northam had earmarked state tax dollars to cover, which means those state tax dollars may be freed for some other purpose. The full scope of the recent flow of federal dollars has been seen in recent legislative meetings, but so far Northam’s specific plans to use them are not known.

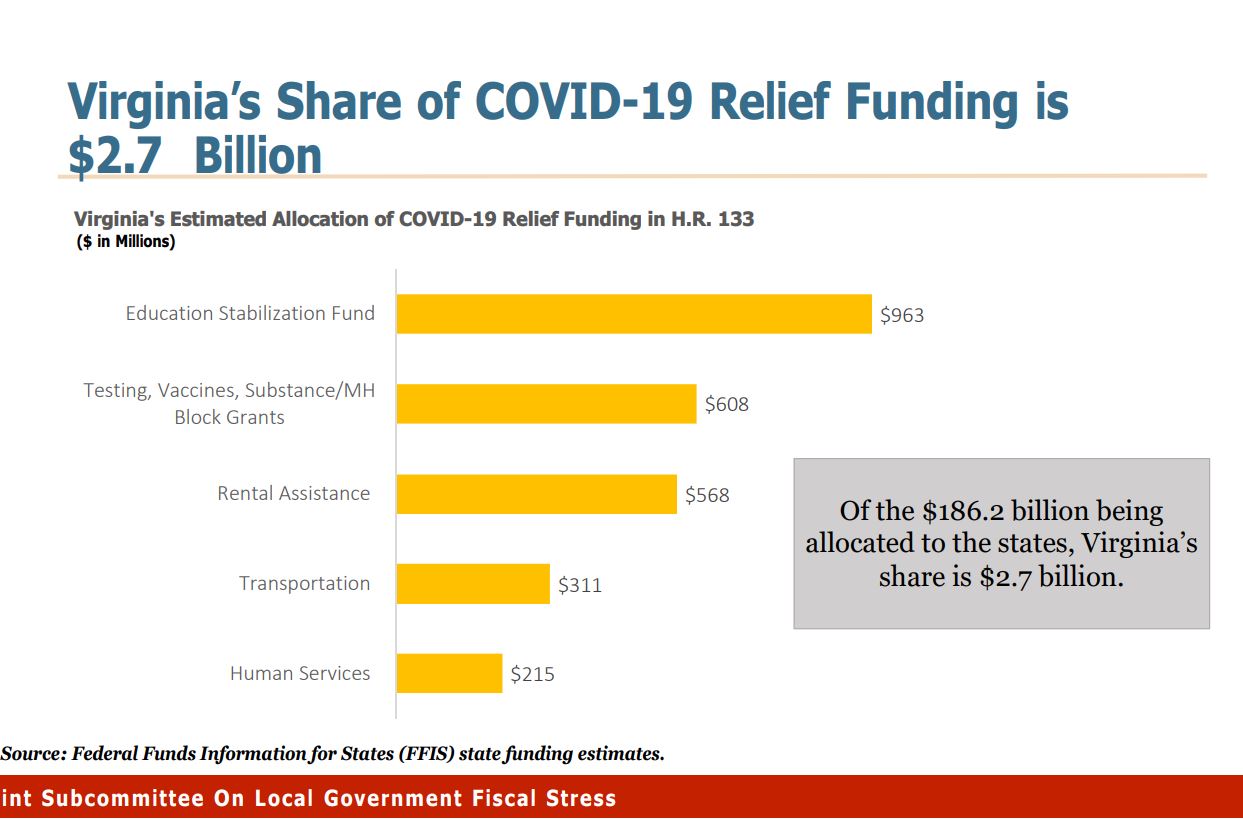

For example, $568 million is earmarked for housing and rental assistance just in Virginia, swamping the state’s efforts in that regard since last summer. In the health arena $608 million will cover vaccinations, testing and mental health challenges from the crisis, and nearly $1 billion will bolster public education, protecting it from the revenue losses caused by declining enrollments. All could result in free cash flow for the General Assembly starting Wednesday to spend elsewhere or save.

The coming inrush of federal dollars was mentioned in passing in recent meetings of the House and Senate money committee, but today’s meeting of the Joint Subcommittee on Local Government Fiscal Stress focused on the topic. Quite a bit of detail is provided in a slide presentation used for the meeting, including an appendix that details the spending decisions made by individual localities (slides 28-32).

In aggregate, 30% of the previous local allocations so far have gone to local public health and public safety payrolls, 16% to distance learning, 13% to small business assistance and the rest to scattered uses. Bath County spent 96% of its allocation on small business assistance, while quite a few spent nothing that way. Richmond City spent 18% on rental assistance, but few spent even 10% of their allocated funds on that.

The legislators were shown information on how the state, cities and counties have recovered from the previous recession, starting in 2009. The state’s tax revenue rebounded in two years, the counties in three, and the cities in four (slide 11). The staff missed the headline number, however: In the years since 2009, state revenue is up 52%, county revenue up 35%, and city tax revenue rose only 24%. The disparity is pronounced.

Part of the explanation is on slide 10. Counties received more than two-thirds of their local tax revenue from real estate and personal property taxes, cities just 54%. Those are based on value and grow faster over time, and counties have more room and appetite for new real estate development.

A panel of local government administrators, including Fairfax Board of Supervisors Chairman Jeffrey McKay, discussed the revenue bright spots (sales taxes, real estate transactions) and danger signs (shrinking commercial leases, tourism-related taxes) seen in their own localities during this crisis. All stressed the importance to them of the Governor’s proposal to provide “hold harmless” funding for their schools, preventing the revenue loss that would normally result from the enrollment losses.

Meghan Coates, Henrico’s Director of Finance, indicated that may need to continue into future years as all the departed students may not return.

The county leaders thanked legislators for the 2020 legislation adding additional “revenue options” for them to consider. Fairfax’s McKay pointed to the prepared meals tax, something Fairfax voters have rejected. It can now be imposed without a referendum. Given the current state of the restaurant industry, McKay said, now is not the time to impose that but “we know long term that’s still the right decision.”

But the data presented today indicate it is the cities, not the counties, that are failing to see revenue grow, even though they have so many more ways to tax their citizens. Right now, only one percent of county revenue comes from meals taxes, and when that equals the six percent cities now receive (it won’t take long), the counties will be that much further ahead.